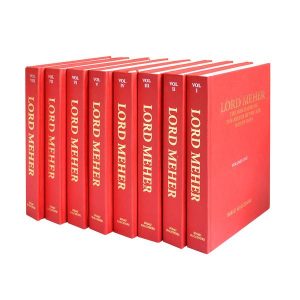

Lord Meher (Meher Prabhu), Reiter edition

Lord Meher (Meher Prabhu), Reiter editionAnalysis of a lengthy text can be a complex matter. This is certainly true of the multi-volume Lord Meher, a devotional and biographical work on Meher Baba (1894-1969). The title is a translation from the Hindi phrase Meher Prabhu. Partisan claims have described this book in terms of a definitive work by Bhau Kalchuri (1927-2013), one of Meher Baba’s mandali (ashram staff). There are complications for such an attribution.

Kalchuri was only one of the entities involved in the development of Lord Meher, originally in Hindi. A translation into English commenced in 1973. The resulting editorial process was intensive. Early supporters of the Reiter edition (1986-2001) maintained that this was the last word on Meher Baba, fastidiously conveyed by Kalchuri. The American devotee Lawrence Reiter (d.2007) was one of the editors; he undertook publication of seven thousand pages (including many photographs). This is sometimes known as the American edition.

The Meher Baba literature is now substantial. As an independent writer, I produced the first critical bibliography on Meher Baba (Shepherd 1988:248-297). The literature was even then prolific, indeed unusually so. Many years later, the dimensions are far more extensive. Critics complain at the rather lavish devotional titles in evidence. Some idioms are controversial. Assessment of this literature now requires considerable time and commitment. Lord Meher is the major stumbling block to easy overview. Some other complexities should not be understated.

I move at a tangent to the “orthodox” perspective on Lord Meher. Many years ago, I composed an unpublished Life of Meher Baba in four volumes, commencing in 1967. I do not claim any status for this work, which merely facilitated my studies in the subject under consideration. I was able to tap some oral transmission, also accessing much literature. Writing that lengthy biography did serve to underline, in my mind, the scope of detail and interpretation possible.

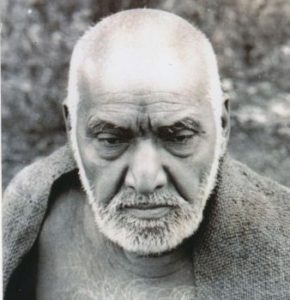

Meher Baba at Meherabad, 1941

Meher Baba is unusual for the sheer amount of materials available concerning him. His career of some fifty years (depending upon how one dates the inception) is described in numerous books, booklets, diaries, and journals. The presentation is attended by a wide variety of literary styles and modes of reporting. Certain of his deceased followers now have full length books about them (e.g., Fenster 2013).

Lord Meher (LM) is by far the longest work on the subject, attended by some linguistic complexities. Writing in Hindi, Kalchuri is reported to have completed his biography in seven months, working non-stop. His contribution was only a small part of the total text. Mistakes in English translation (and possibly the obscure Kalchuri text) were fairly numerous. The translator was Feram Workingboxwala (1901-1980), a Parsi devotee of Meher Baba. Feram had a limited knowledge of Hindi, and Bhau never read his translation, having some difficulty with English. Some of the extending materials in LM were translated by Feram from Gujarati and Marathi diaries and memoranda.

From 1974 onwards, substantial materials were added to the existing LM text, mainly by David Fenster, including diaries and personal accounts from many Indian and Western devotees. An online edition commenced some years after the Reiter volumes were published, often being cited as authority. The online editor is David Fenster, Kalchuri’s son-in-law, an American devotee strongly involved in the overall editing dating back to the 1970s. Many revisions and additions have occurred in the online version.

The Reiter edition very briefly mentioned the translation and editing process on the copyrights page. Kalchuri’s foreword informed that the secretary Adi K. Irani “placed his office records at my disposal and allowed Feram Workingboxwala to assist me in compiling the material for this book, and translating pertinent documents from Gujarati and Marathi into English.” Kalchuri also acknowledges the oral contributions from Meher Baba’s surviving mandali at Meherazad and Meherabad ashrams. Numerous other devotees are also named in this respect. The identity of sources stops there.

The Reiter edition featured endnotes that do not establish the nature of sources and translations. The online edition has no notes, but does feature pop-up comments. The endnotes in Reiter include some interesting information, but make no attempt to analyse sources, which are not mentioned. The “Kalchuri” text was regarded by Reiter (and others) as needing no explanation in this respect.

The analytical assessor of LM will see the text in terms of undefined sources and translations. The lack of annotations and bibliographies has disconcerted some readers. What source did this statement come from? What was the original language? Who edited the source or translation? What is the degree of accuracy involved? These are some of the questions relevant to any full discussion.

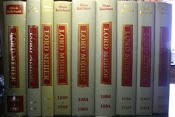

Adi K. Irani, 1962

The office records of Adi K. Irani (secretary to Meher Baba) were almost legendary by the 1960s. These files included diaries and large quantities of correspondence. The languages represented were English, Marathi, and Gujarati. This archive was not on open view, being stored at Khushru Quarters in Ahmednagar. Most devotees of that period were content with general circular information via Adi and Mani S. Irani. I was an exception, wishing to know more about the elusive records.

I was in correspondence with Adi K. Irani during 1965-66. I found him helpful on some points. However, he was reluctant to discuss matters of history that were not already available in published literature. For many years he had been supplying “life circulars” on current events. Adi did not feel inclined to make his archive better known.

I had learned that a vintage diary in English, by Ramju Abdulla, was in existence, being relevant to the early 1920s. I wanted to know more about this document, but met with disappointment. This diary was not published for another thirteen years (Deitrick 1979). That diary was one of those read dismissively by the Yoga enthusiast Paul Brunton almost fifty years before.

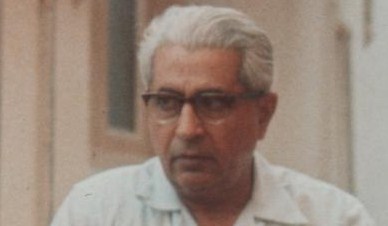

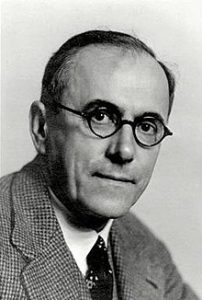

Charles B. Purdom

Still a major work on Meher Baba, during the 1970s, was The God-Man (1964). This is skeletal in detail by comparison with the total data now available. The author was Charles Purdom (d.1965), one of the earliest Western followers. I met Purdom (more than once) during the last months of his life. He was a fluent talker and could still lecture. I remember well that he prepared a liberal and non-sectarian paper on Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (d.1886), read out at a London meeting by Molly Eve in his absence due to illness. Purdom’s speech was free of the devotional jargon that subsequently increased in the movement, i.e., Beloved and lovers, Avatar of the Age.

It is very difficult to describe Charles Purdom as a devotee. He did not express devotion at all, but instead a muted form of respect. He was averse to exaggerated and repetitive stylisms. His book The God-Man is impersonal in tone, contrasting with many other partisan writings. Purdom had retained the discreet vocabulary and literary style of a 1930s British independent follower of Meher Baba (Purdom 1951). See the index references in Shepherd 2005:315.

Becoming well known was an error in the LM translation of a statement about Azar Kaivan (d.1618). This was originally reported in an annotation to another book (Shepherd 1995:854 note 152). Subsequently, this error (together with the revision supplied by me) was duly mentioned on a Wikipedia page by Simon Kidd, an academic real name editor on the web encyclopaedia. Kidd was no stranger to Kaivan, having studied the Dabistan in Cambridge, under the guidance of a well known scholar. However, his intervention was opposed by a pseudonymous Wikipedia editor claiming that Lord Meher was infallible text. As a consequence of more than one opposition from devotee interests, the revision was excised. However, the opponents lost all reference to their own “infallible” text in the process of Wikipedia editing at the same article.

The defective Reiter edition has the words: “After that, the last one, Dastur Azer Kaiwan, was false and obtained the sacred seat and started collecting money” (page 1020). This was belatedly reworded in the online Fenster edition as: “But after Dastur Azar Kaivan, a false, deceitful dastur obtained the sacred gaadi and started collecting money” (page 903, accessed 28/11/17). No reference was made anywhere in the Meher Baba literature to the earlier revision which appeared on Wikipedia. The dogmatic mistake had never happened. It is well known that the rendition of a name as Kaivan follows my publications and online articles, in contrast to the Kayvan found on Wikipedia and elsewhere. The online LM editing process might still have to revise the reference to Dastur Azar Kaivan in view of relevant arguments concerning priestly identities. The date of any revision should be duly recorded, and with full references.

Lord Meher, Indian edition 2005

Due analysis of a text, religious or otherwise, must transcend dogmatism. See Meher Prabhu/Lord Meher. There is evidence of a critical attitude to LM amongst a minority of Meher Baba devotees, including Christopher Ott, an American. He is evidently very familiar with the genesis and development of LM. His contributions include History of Lord Meher. Ott emphasises elsewhere that the history of the editing process is “long and complex.” He makes a striking disclosure: “I have sworn privacy to one witness and am waiting for that person to die before sharing that person’s emails, confirming what more there is to say.”

The same informed commentator reveals the existence of “at least eleven versions of Lord Meher, none of them exactly the same.” One of these versions is the original handwritten Hindi manuscript of Bhau Kalchuri, “never made public.” An elaborated English version was achieved by Workingboxwala, “with additions and corrections inserted and compiled by David Fenster.” This version, dating to the early 1980s, is accessible. A subsequent version was the Reiter edition of 20 volumes (or more realistically, 13 vols in terms of binding). In 2005, an Indian edition of Reiter exhibited “some major changes.” Meanwhile, LM went online in 2002. The current online edition is “redacted monthly,” a process which has involved “drastic and constant changes, with both good corrections and grave new inaccuracies.” All quotes here are from Ott, “Original Lord Meher” (30/06/2017), featuring at Meher Baba Thoughts (formerly open access online).

Ott makes additional comments of a radical nature. “There is currently no way to systematically ‘fact-check’ the events in any of these [LM] biographies.” The same commentator suggests that future scholars will resort to a new version of LM based directly on the sources, including extant diaries and correspondence.

In contrast, for many years, Western devotees were believing that Kalchuri was the sole author (and even translator) of LM. Ott entitles one of his blog communications in dramatic terms: “The terrible truth about who translated Lord Meher.” Such revelations may encourage a more widespread disposition to analyse LM text.

Many years ago, I wrote the independent work Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal. Some American devotees maintained that the subject was Indian. Meher Baba was certainly born in India, but his parents were Irani Zoroastrians originating from Yazd. The controversial title was ventured in relation to Irani Zoroastrians who migrated to India, while retaining ethnic and linguistic features distinct from the Parsi population. For instance, Meher Baba and his father (Sheriar Mundegar Irani) spoke Dari. Another consideration is that Meher Baba was not typical of contemporary Indian gurus like Rajneesh. The tendency to associate him with Hinduism is offset by such details as the Zoroastrian kusti girdle he wore in his early years until 1925 (Fenster 2013, 1:181). Another version, closely associated with Ott, maintains that he wore the kusti all his life; this version is contradicted by a more recently published mandali report informing that Meher Baba discarded the kusti girdle in 1931.

Irani Zoroastrians are descendants of the original population of Iran in pre-Islamic times. To describe them as Iranians is not an error, nor a crime. The title of my book was not intended to be politically evocative, but to grant the subject a due ethnic perspective. The Wikipedia article on Meher Baba is maintained by pseudonymous Western devotees. These partisan editors deleted Iranian Liberal from a list of sources; this annotated book featured the first critical bibliography. Such cordoning gestures have elsewhere been considered insular and arbitrary. I decline to be intimidated by such tactics (including hostile remarks on talk pages). Wikipedia is not a primary source for university academics and researchers.

The informed American devotee Ward Parks refers to the 2005 Hyderabad edition of LM as “a somewhat emended and corrected text.” Both the American and Indian published editions of LM include selections from the 1920s Tiffin Lectures (silent discourses), not well known until recently. Parks informs:

Lord Meher was written primarily as a biographical account of Meher Baba’s life; and while it is rich in quotation from Meher Baba’s words, it was never meant as a critical edition of any of his messages and should not be taken as such…. Bhau does not ordinarily quote from his sources verbatim or with minimal rewrite…. Often he reduces extensive discourses into abridged versions that convey the essence or gist. On other occasions he selects main points from different junctures in a talk and works them together into an integral message that accurately expresses much of Meher Baba’s original thought but cannot be said to follow his verbiage except in patches. (Parks 2017:520)

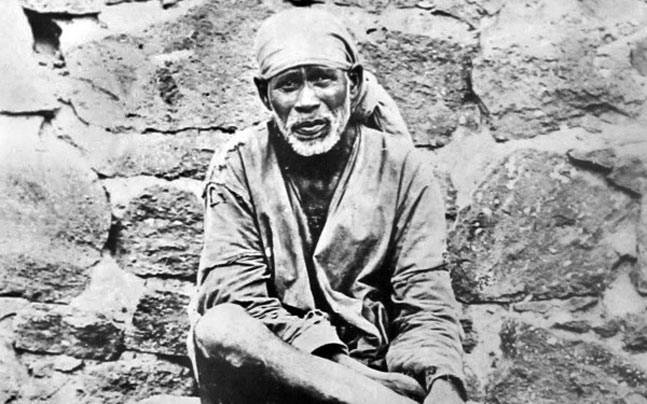

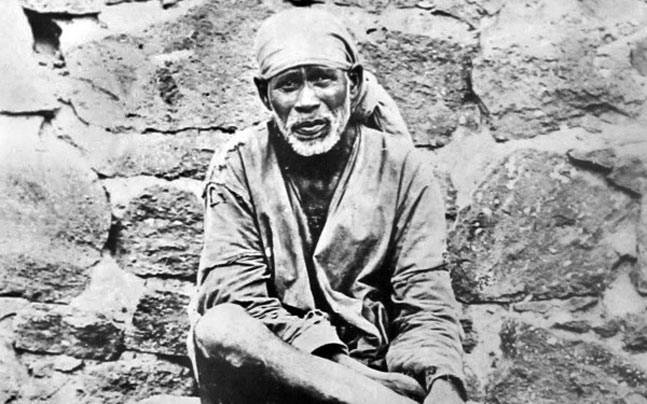

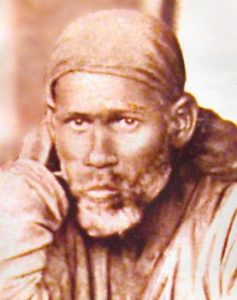

Shirdi Sai Baba

The first Reiter volume included chapters on the five “masters” of Meher Baba, including the famous Shirdi Sai Baba (d.1918). Those chapters are informative to a degree, though not by any means exhaustive portrayals. Now well known is the eccentric “Kalchuri” statement that Sai Baba smoked “a chilum pipe of opium” (Reiter edn 1986:64). This misleading assertion caused confusions, later being excised from the online edition as an error (David Fenster has stated in an email that the error was caused by faulty editing). Shirdi Sai was far more reliably reported in early Marathi sources (Dabholkar and Dixit) as a smoker of tobacco (Warren 1999:106; Shepherd 2015:114; Shepherd 2017: viii, 65). Narasimhaswami affords a confirmation of tobacco. The chilum was loosely associated with opium, but also used to smoke other substances, including tobacco.

In 2017, Fenster mentioned adding a note to online LM, suggesting the possibility that a small amount of opium or hashish was at times added to the chilum of Shirdi Sai, for the purpose of alleviating asthma. This suggestion was prompted by a web trawl in November 2017, communicated to Fenster by email. The critic influenced the unwary Fenster on this point. The trawl was presented in terms of “research.” Fenster ignored my email protest at his projected new note, citing as his authority a presumed statement of Meher Baba which makes no reference whatever to the imagined contingency. This statement had been favoured by the critic, who did not bother to read any books on Shirdi Sai. The web trawler explicitly stated to me (by email) that he had no interest in Shirdi Sai, whom he regarded as an illiterate village faqir of minor consequence.

The web trawl, which strongly influenced Fenster, located a recent surmisal that Shirdi Sai smoked a sparing amount of bhang for medicinal purposes. The critic was influenced by a 2015 blog of Shri Datta Swami (a contemporary guru), evidencing a preoccupation with allergy medication, namely Citrazin, Uni-carbozon, and Avil. Bhang was here viewed as the equivalent of pharmaceutical tablets. The alleged act of smoking bhang was supposedly an antidote to “illness based on allergy, which is serious cough.” The scenario here is very conjectural, and does not count as “research.” The convergence of diverse contemporary assumptions about what Shirdi Sai smoked is here obscuring what early sources stated a century ago.

Fenster provided two versions of his new suggestion in separate emails. In the first, he said that “sometimes a small amount of opium or hashish would be added to the chilum to alleviate Sai Baba’s asthmatic condition.” When I objected to this innovation, he modified the phraseology, but would not abandon his contention as to possibility. He showed no familiarity with Shirdi Sai literature. He gave the impression that he would shortly be placing online his innovation. However, Fenster subsequently withdrew his contention when informed of more relevant data.

The web trawler stated in an email to myself (04/12/17): “Shirdi Sai Baba occasionally used a tiny amount of opium or cannabis to alleviate a life-long asthmatic condition.” This was a reference to smoking, effectively relying on the mistaken suggestion of Fenster, who had been influenced by the same insistent trawler. The reciprocal confusion evidenced in these emails was substantial, creating imagined fact from mere surmisal.

The trawler critic subsequently changed his mind, apologising for his error. This was because he read more deeply on the subject of Shirdi Sai Baba, grasping that he had been misled by web features amounting to opinion at best and “fake news” at worst.

The purported statement of Meher Baba, quoted by Fenster (email 27/11/17), reads: “Seekers then used not only wine but also hemp, heroin, hashish and opium; so much so that even sadgurus would indulge in them. Sai Baba used to smoke a chillum and Upasni Maharaj smoked beedies.” This was the version found in the online edition of LM. No source is supplied for the 1929 statement. Furthermore, the same LM “Kalchuri” statement of Meher Baba has variants, e.g., “You have heard stories that Sai Baba used to smoke a chilum pipe and Upasni Maharaj smoked bidis” (Reiter edn:1227). Fenster made no mention of the stories in his online edition.

Extending details are relevant. The same passage, of which the quotation is part, refers to “the ancient past” (Reiter edn:1227). This was when seekers and sadgurus supposedly used the substances specified. The ancient chronology is confirmed by an accompanying reflection of Meher Baba: “Eventually during those times, ordinary people indulged in these intoxicants for the wrong reasons” (ibid). A lengthy period is indicated. Fenster emails (influenced by another party) opted to place the “ancient past” in the early twentieth century at Shirdi. Confusion thus enveloped an early Meher Baba statement, even supposing that the statement is correct in rendition (all details of origin and transmission being absent in LM). Not all statements of Meher Baba were uniformly rendered, or presented accurately, especially when translation was involved from one language to another. The error relating to Azar Kaivan is a case in point, one which misled readers for nearly thirty years.

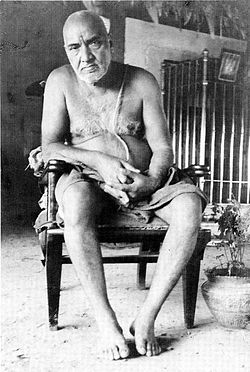

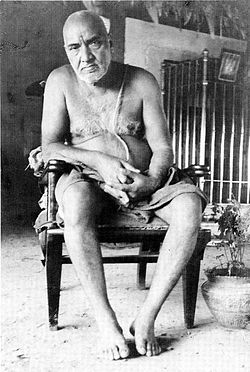

Upasani Maharaj at Sakori, 1930s

In the confusing LM passage at issue, the impression was given to unwary readers that Upasani Maharaj (d.1941) smoked a drug substance over a lengthy period. In reality, Upasani smoked bidis (country tobacco cigarettes) for a few weeks only. He did this solely because of a medical insistence that he resort to tobacco for the purpose of assisting bowel motions, at a point of crisis prior to a necessary surgical operation. Upasani himself disliked cigarettes, and had to be persuaded to smoke (Shepherd, Radical Rishi: A Biography of Upasani Maharaj, chapter 53). He was an orthodox brahman in the sense of being opposed to drugs and alcohol, tobacco also not being in favour.

Upasani Maharaj is a subject closely converging with Meher Baba, though for the most part neglected in the Meher Baba literature. Due analysis of Upasani biography (and teaching) is long overdue. Upasani is also strongly linked with Shirdi Sai Baba, in situations requiring more detail than is customarily supplied.

Generations may elapse before all discrepancies in the lengthy composite work Lord Meher are resolved. Meanwhile, a dogmatic celebration of infallible text is not appropriate.

Bibliography:

Deitrick, Ira G., ed., Ramjoo’s Diaries 1922-1929 (Walnut Creek, CA: Sufism Reoriented, 1979).

Fenster, David, Mehera-Meher: A Divine Romance (3 vols, 2003; second edn 2013).

Kalchuri, Bhau, Feram Workingboxwala, David Fenster et al, Lord Meher (Reiter edn, 20 vols, 1986-2001).

Kalchuri et al, Lord Meher (revised edn, 8 vols, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh: Meher Mownavani, 2005).

Kalchuri et al, Lord Meher online, ed. David Fenster.

Parks, Ward, and Meherwan B. Jessawala, eds., Meher Baba’s Tiffin Lectures as given in 1926-1927 (Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Foundation, 2017).

Purdom, Charles B., Life Over Again (London: Dent, 1951).

——–The God Man: The life, journeys and work of Meher Baba with an interpretation of his silence and spiritual teaching (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Meher Baba: An Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

——–Minds and Sociocultures: Zoroastrianism and the Indian Religions (Cambridge: Philosophical Press, 1995).

——–Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

——–Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2015).

——–Sai Baba: Faqir of Shirdi (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2017).

Warren, Marianne, Unravelling the Enigma: Shirdi Sai Baba in the Light of Sufism (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

December 2017 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 74

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

Lord Meher (Meher Prabhu), Reiter edition

Lord Meher (Meher Prabhu), Reiter edition

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Shirdi Sai Baba

Shirdi Sai Baba