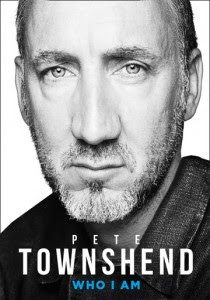

The recent autobiography of Pete Townshend (born 1945) is entitled Who I Am. This book has aroused diverse assessments, including my own contribution. Townshend, a guitarist and songwriter for The Who, became known for an affiliation to the Irani mystic Meher Baba (1894-1969). A very obvious discrepancy is that religious sympathies did not mix too well with the career of a rock star, in this instance featuring a long term alcohol problem, plus a susceptibility to hard drugs during the years 1980-81.

The British rock group known as The Who emerged in the mid-1960s, eventually becoming superstars in America. They were icons of the Woodstock Festival at Bethel in 1969, an entrepreneurial event celebrated in a well known film. Ironically, Pete Townshend did not approve of the hippy venue, which he described as a mudbath laced with LSD. The previous year, he had declared himself to be a follower of Meher Baba, who was strongly opposed to LSD and other drugs. Townshend ceased his intake of marijuana (cannabis), and did not revert to LSD.

The stage performance of Townshend was noted for athletic leaps and the smashing of guitars. The “destruction art” was derived from his attendance at Ealing Art College and the questionable ideas of lecturer Gustav Metzger, who did however, disagree with Pete Townshend over the issue of a new commercial promotion. Townshend writes: “I was supposed to boycott the new commercial pop form itself” (Who I Am, p. 115). He also admits: “At a psychic level the Angry Yobbo, or hooligan, had seared himself into my soul” (p. 194).

In 1970, by his own account, Townshend began to experience “regular manic-depressive episodes” (p. 210). His very questionable remedy for this setback was to drink alcohol. To such an extent, indeed, that he cultivated a habit of drinking brandy while performing on stage. His situation was surely not assisted by the activities of his fellow performers Keith Moon and John Entwistle, both of whom were alcoholics developing a partiality for cocaine. The ill-fated career of Moon ended in 1978, when that drummer overdosed with medication for his chronic alcoholism.

Townshend was evidently upset by this development. “The incredibly charged emotions around Keith’s death made me lose all logic” (p. 309). Now suffering from impaired hearing, Townshend had previously resolved not to tour again with The Who. Yet at this juncture, he favoured a replacement drummer, also being keen to undertake concerts again in 1979. His alcoholism became evident. In 1980, his resistance failed when he was offered cocaine. A drastic two years of addiction followed, eventually including a resort to heroin.

The effect on Townshend was catastrophic. At one point he came close to death in a Chelsea hospital. His reckless disorientation included the well known incident where he jumped a fence into the bear pits at Berne, Switzerland. “I could have been eaten alive” (p. 330). There were other dangers also. Medical doctors knew that he had to break the bad habit of night club attendance, the root of his troubles. He was told to take up physical exercise instead, or invite certain death; he wobbled badly, and eventually had to seek help in California. A month of neuroelectric therapy switched off the addiction. However, anxiety attacks and psychological unravelling required five years of psychotherapy during the early 1980s.

The rock star continued his musical career. He also became an editor at the London publishing house of Faber. These events are well known; rather more obscure is the phase of Meher Baba Oceanic. This centre, established by Pete Townshend at Twickenham in 1976, featured facilities for filming and recording. Something went wrong; the project changed name to Oceanic, becoming a purely private enterprise relating to Townshend’s musical career. Different explanations were given by onlookers at the time. Some Meher Baba devotees implied that Townshend had lost interest in the figurehead as a result of his drug and alcohol excesses. This judgment is contradicted by his own subsequent statements, which strongly indicate a continuing allegiance to Meher Baba.

The available data suggests that Townshend was basically confused in his project of Meher Baba Oceanic. This conclusion is inescapable when reading a report written by his close friend Richard Barnes:

He [Townshend] was constantly initiating new ideas and concepts, but in a few days or weeks his mind would have raced ahead to something new…. At first there were facilities for filming and editing, then it was video, then it was recording. Pete was like a rich kid with too many toys…. I was staggered at the stupidity of some of the people Pete had given key jobs. By mistake, the tape would be wiped off after a day’s recording session, or a video would be ruined because somebody forgot some vital function…. The incongruous combination of recording studio and Baba workshop under one roof was a typical, badly thought-out move by Pete. The whole place [Meher Baba Oceanic] seemed to be a reflection of his own confused state of mind at that time. (Quoted in Geoffrey Giuliano, Behind Blue Eyes: A Life of Pete Townshend, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1996, pp. 144-5)

The most controversial event in the life of Pete Townshend occurred in 2003, when allegations surfaced on the media about his purported interest in child pornography on the internet. He denied these allegations. Some critics were persistent, including partisans of a rival guru to Meher Baba, who were eager to imply that Townshend’s conjectural role as a paedophile amounted to proof of Meher Baba being a deficient guide (the rival was Sathya Sai Baba). Sectarian thinking often exhibits obsessive peculiarities.

The autobiography Who I Am supplies details that negate the allegations (pp. 482ff.). The home of the rock star was surrounded by reporters and camera crews intent upon a celebrity scoop. Townshend was taken to a police station. However, he was released on bail. Forensic examination of his computers could not find any evidence to incriminate him. These and other matters are mentioned in Who I Am. The allegations may accordingly be set aside.

Unless otherwise specified, all page references above are to Pete Townshend, Who I Am (London: HarperCollins, 2012).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 51

Copyright © 2013 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.