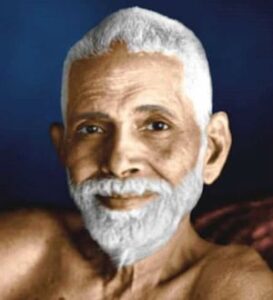

Ramana Maharshi

A version of Advaita Vedanta was taught by Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950). Report of him was pioneered in India by Narasimhaswami, and in the West by Arthur Osborne and others. Ramana was subsequently assimilated to some controversial American versions of Nondualism. The Western “neo-Advaita” has aroused scepticism.

Ramana was the son of a brahman (a member of the Hindu priestly caste) who worked as a lawyer at Tiruchuzi, a village in the Tamil sector of South India. His real name was Venkataraman Iyer. After his father’s death, some of his relatives moved to Madurai, a city in Tamil Nadu. Here in 1896, while still sixteen, Ramana underwent an experience variously described in terms of “awakening” or “death.” The belief subsequently developed that he gained “enlightenment” or “realisation” at this time. Another phrase used is “sudden liberation.” Different accounts exist of this episode, together with fragmentary reminiscences of Ramana himself in much later years. “There are many interpretations of Ramana’s teaching, and of the nature of Ramana’s enlightenment experience itself” (Friesen 2006:2).

Caution is required. “Later followers subsequently rationalised this event as a sadhana [spiritual discipline] which lasted half an hour and was completed on the spot. They wanted to believe that he [Ramana] had gained the ultimate realisation known as sahaja samadhi in this brief period of awakening, though he himself did not say that” (Shepherd 2004:153).

In an early biography, B. V. Narasimhaswami reported that divergent interpretations of this Tamil Advaitin were current: “He speaks little and only as to what is asked. His works are cryptic and are capable of diverse interpretations. Shaktas go to him and think he is a Shakta. Shaivas take him for a Shaiva. ShriVaishnavas find nothing in him inconsistent with their Vishishtadvaita ideal. Muslims and Christians have found in him elements of their ‘true faith’ ” (Narasimhaswami 1931:197-198).

According to Dr. Friesen, Ramana was influenced by Tantra and neo-Hinduism, also Christianity. “Ramana should not be regarded as a traditional advaitic sage” (Friesen 2006:5). This theme has been strongly resisted by partisans of Ramana, who urge that his “realisation” is the sole gauge for his teaching.

Ramana did have some previous knowledge of meditation prior to his experience as a 16 year old, and he derived his teaching of Self-Enquiry from books that he read before he wrote any of his own. Even more importantly, Ramana did not himself have the certainty at the age of 16 that his experience was permanent. And he later disputed the necessity of a state of trance for enlightenment. (Friesen 2005:37-38)

Narasimhaswami supplied a description of the 1896 “death” episode, implying a sadhana of control on the part of the subject. Ramana actually said: “The fact is, I did nothing.” The influential version of Narasimhaswami resorts to the first person “I” in statements attributed to Ramana. However, the author does acknowledge his innovation by informing: “The exact words have not been recorded.”

Ramana retrospectively referred to his “absorption in the Self [atman].” There is the complexity that he also described his “awakening” in terms of possession, apparently his early reaction to the experience, which he conveyed to his first biographer Narasimhaswami (David Godman, Life and Teachings).

The “awakening” occurred at Madurai, where Ramana was afterwards in the habit of visiting the Meenakshi temple, associated with Shiva-bhakti and the sixty-three Shaiva Tamil saints of the nayanmar tradition. “After the Awakening I went there [to the temple] almost every evening” (Osborne 1954:23). He had read a book (the Periya Puranam) on those saints which inspired him. In his later life, he acknowledged the significance of bhakti (love, aspiration), which is something quite different to the Advaita doctrines. Indeed, his own report states, of his continuing visits to the Meenakshi temple (after his “awakening”), that he would sometimes pray for the descent of divine grace “so that my devotion [bhakti] might increase and become perpetual like that of the sixty-three saints” (Osborne 1954:23). This is not the language of Advaita, contradicting the much later devotee insistence upon an immediate non-dual “enlightenment.”

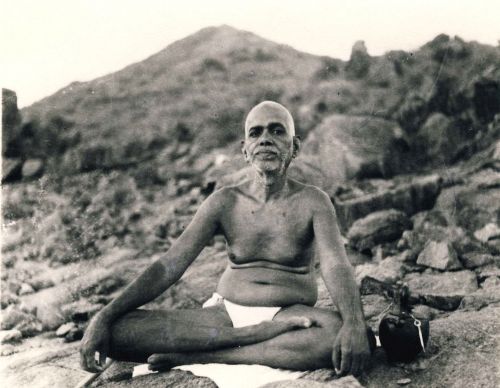

At the end of August 1896, Ramana experienced “a deep state of absorption in the Self” to quote a popular online version. He soon left home, journeying north to the pilgrim town of Tiruvannamalai, there staying in temple precincts while subject to an abstracted state. He eventually settled in caves at nearby Arunachala Hill, strongly associated with the deity Shiva. The basic feature of that early period is one of acute introspection. He was no longer a brahman, having jettisoned the sacred thread signifying caste status. He was now an ascetic sadhu wearing a loin-cloth, not the ochre robe of Vedantic renunciates. Ramana was not an official Vedantin or sannyasin.

Devoted attendants saw to his simple needs and protected him from intrusions, diverting unwanted sightseers who thronged the pilgrim locale of Arunachala. At first, his introspection was so acute that food had to be pressed into his mouth for the purpose of keeping him alive. Afterwards, he is reported to have accepted only a single cup of food daily; he was accordingly emaciated. For years (until circa 1906) he would not speak to visitors. Indeed, he is reported to have lost his ability to speak normally until that juncture. A different kind of problem was jealous sadhus, local holy men who resented his increasing fame.

A visiting group of sadhus expressed an extremist belief that their own distant sacred hill was home to a rishi who had been practising austerities for thousands of years. This entity had purportedly told them to abduct Ramana for initiation, after dramatically preparing him for the attainment of occult powers or siddhis. “Whether hemp addicts or alcoholics (or both), they evidently entertained some of the more fantastic and predatory ideas associated with Tantric Yoga” (Shepherd 2004:155). Ramana is reported to have made no response to these visitors; he never expressed esteem for siddhis, which are an unhealthy preoccupation.

Ramana was reputed to be in samadhi, signifying spiritual absorption; the word samadhi comprises a diffuse blanket term in popular usage. The basic event discernible is that Ramana emerged from this absorption over a lengthy period, gradually normalising in his response to the outside world (while retaining his spiritual awareness, according to his own account). “At some obscure date he began to walk about the hill instead of sitting motionless” (ibid:154). He would refer to himself as a jnani (knower), not as a Yogi. Ramana warned about the pursuit of siddhis. He was averse to Yogic exercises, which he evidently viewed as a complication.

Ramana Maharshi at Arunachala

In 1922 he moved down to the foot of Arunachala Hill, taking up residence at the site which became known as Ramanashram. By 1926, the increasing crowd of visitors and devotees was sufficiently large to hinder his customary daily walk around the hill, which thereafter ceased, apparently because nobody wanted to stay behind at the ashram without him.

The concession to public spotlight, at an ashram, was accompanied by some unusual characteristics. Ramana retained a very simple lifestyle. He did not refuse visitors, but could seem indifferent to company. His statements tended to brevity; he seems to have abbreviated his jnani emphases if he considered that the audience was uncomprehending. Preferring informal conversation, he was notably averse to giving initiations, an accepted part of the popular Hindu spirituality.

Ramana was often requested by admirers for permission to adopt the life of renunciation. He generally opposed this desire, a persistent trait which caused puzzlement. According to him, the effort needed was internal, and nothing to do with the formal vow of sannyas (renunciation). He evidently regarded many of the renunciates as distracting sources of misinformation.

He favoured the discipline of vichara (self-inquiry), which he advocated to many visitors in the spirit of Advaita (non-dualism). He disliked the customary expositions of Vedanta associated with pundits, who exercised a rote learning of scriptures. Ramana was completely independent of organisations like the Shankara Order.

Vichara is viewed as an innovative feature of his communications, relating to the “realisation of the Self,” a Vedantic theme prone to abuse and facile interpretation. The protractedly introverted and normalising “realisation” of Ramana, in his early years, contrasts with glib assumptions about achieving “Nondualism” and “Self-realisation.” Those contractions are frequently encountered in both India and the West. The fantasised “short cut” is not convincing to some analysts, though very appealing to overnight gurus. The facile scenario of effortless enlightenment is well known in relation to the American guru Andrew Cohen. Ramana’s emphasis on the constant practice of self-enquiry is often abbreviated to slogans like “Be as you are,” singularly convenient for exploiters. Related mantras have become pervasive in the “new age” of commercial mysticism.

A lop-sided view of Ramana Maharshi in his later years, as an abstracted contemplative, has been corrected by partisan writer David Godman. Ramana industriously prepared food at his ashram for about 15 years; he also closely supervised building work during the 1930s. He was evidently not too keen about having to sit in the audience (darshan) hall where he received all visitors; he often referred to that hall as his prison.

Although an unusual teacher (and one who did not describe himself as a guru), Ramana was not venturesome in the area of social reform. According to a well known commentator, he “did not disapprove of orthodoxy in general” (Osborne 1954:77). Ramana certainly did not condemn caste norms, which were reflected to some extent in the emerging ashram management run on conservative lines. The leader of management staff was his brother, a renunciate who wore the traditional ochre robe. The increasing number of visitors, during the 1940s, imposed changes, including the building of a new and more imposing audience hall to which the sage was averse.

“A brahman code prevailed in the kitchens, where only brahmans could prepare the food” (Shepherd 2004:156). However, free food was dispensed to sadhus and the poor on a daily basis. The formalism of management officials is reported to have been resented by visiting devotees; there was even a request that the management be removed (Osborne 1954:120).

The ashram dining hall was partitioned, the orthodox brahmans sitting to one side, while on the other side sat the lower castes, non-Hindus, and liberal brahmans. “Sri Bhagavan [Ramana] says nothing to induce Brahmins either to retain or discard their orthodoxy” (Osborne 1954:133). Nevertheless, “he often turned a blind eye when devotees violated caste rules” (Godman, Bhagavan the Atiasrami). His perspective is described in terms of: “He had no opinions on these scripted events [occurring in the world], and no desire to change their course” (Godman, Bhagavan and Politics).

This situation can easily disappoint. However, Ramana did make certain gestures in defiance of caste biases. During the daily recitation known as Veda parayana, he allowed all visitors to attend. This was “a flagrant violation of caste rules,” because only the higher castes were entitled to hear scriptural chants. Ramana ignored related complaints from high caste persons. A visitor from North India once disapprovingly confronted him on this issue. Ramana “curtly told him to sit down and mind his own business” (Godman, Atiasrami, linked above).

In some of his statements, Ramana appeared to endorse the political career of his contrasting contemporary Mahatma Gandhi. These two entities never met. Untouchables (Dalits) were not allowed into Hindu temples, including the strongly resistant Shiva temple at Tiruvannamalai. Gandhi attempted to change the conventional high caste attitude. He was murdered by a brahman assassin.

After the death of Ramana Maharshi, the belief developed amongst devotees that the saint “guides whoever approaches him” (Osborne 1954:194). Such beliefs about posthumous guidance are also found in relation to other deceased Indian saints like Sai Baba of Shirdi. Hagiography easily accumulates in such climates of expectancy.

“Current Western gurus, influenced by the Ramanashram, have insisted that vichara (self-enquiry) is the ideal approach for all seekers” (Upasani Maharaj and Ramana Maharshi). This contention is not universally agreed upon. The popular Advaita movement in the West has favoured a notion that atma-bodha is “directly experienced by everyone,” a contradiction to the effort mentioned elsewhere. Be as you are, thoroughly lazy and needing improvement. The commercial network urges that everyone is a jnani, a simplistic belief very convenient for predatory gurus. The misleading tide of “nondualism” literature has done nothing to create discernment.

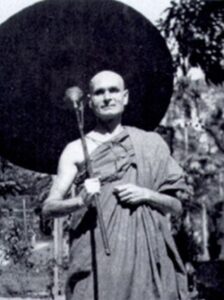

Paul Brunton in India, 1930s

Ramana has been credited with a unique teaching, a theme disputed by others. Adding to confusions was Paul Brunton (1898-1981), a British occultist whose commercial books became famous. There are partisans of Brunton who extol his spiritual connection with Ramana; the evidence confirms something less exemplary.

Brunton early joined the Theosophical Society, from which he later parted company. However, strong Theosophical influences are discernible in his output, along with other related currents of the middle class British “esotericism” of the 1920s. Brunton claimed powers of clairvoyance and clairaudience, including astral travel. He composed numerous articles for the enthusiast periodical Occult Review. The British occultist became fixated on the siddhis (powers) of Yoga, including telepathy. “It seems that one of Brunton’s disappointments with Ramana was that Ramana did not impart more special powers to him” (Friesen 2005:17).

Brunton (then Raphael Hurst) visited the ashram of Ramana for two weeks in January 1931. He moved on to see other teachers and celebrities. After making a second visit to Ramana, he returned to England. Brunton believed that he had experienced samadhi for an hour at Ramanasramam. Yet Ramana himself seemed critical of the account found in Brunton’s A Search in Secret India (Friesen 2005:20). That book is notorious for omissions and misreporting (Shepherd 1988:146-176). The British writer made a “later confession that he used Ramana as a ‘peg’ for his own ideas” (Friesen 2005:22).

Frederick Fletcher, alias Bhikku Prajnananda

In Secret India, Brunton wrote as though he were an objective and critical narrator. Analysis of the underlying situation reveals strong Theosophical, British occult, and Yoga influences upon the astral traveller. His tangible travelling companion in India was Frederick Fletcher (born 1877), an Englishman who had become a Theravada Buddhist monk, assuming the name Bhikku Prajnananda. Fletcher was a fellow ex-Theosophist whom Brunton had met in London years earlier. The monk acted as a guide for Brunton and introduced him to Ramana (whom Fletcher respected). Brunton could not speak any Indian language.

As a consequence of his later story told to a press reporter, Fletcher gained celebrity as the Buddhist adept who had lived for a year (in 1922) at the major Tibetan Mahayana monastery near Shigatse (“British Major, Buddhist Monk,” The Age, December 1941). The report is revealed as being exaggerated. In reality, Fletcher was part of a small British scientific expedition to Tibet, having the role of a geologist and transport officer.

Fletcher invented Theosophical auspices for his secular expedition. The misleading title of Lama Dorje Prajnananda is associated with him. He was supposedly ordained as a Gelukpa novice at Shigatse. If so, he subsequently returned to Ceylon in 1924 (or later), where he took the ordination of bhikku in a Theravada community. A Sergeant-Major in the British army during World War One, he had been upset by the suffering he witnessed, gaining incentive to renounce the world. He subsequently established an “English ashram” at Rangoon in Burma (the details are very vague).

Bhikku Prajnananda is typically missing from Secret India, despite being a major figure in the obscured cast. Brunton instead refers to this companion as a “yellow robed Yogi” named Subramanya (In Search of Brunton’s Secret). The impression was conveyed of an Indian Yogi. This identity switch was probably a result of Brunton’s preference for Yoga and siddhi auspices, anglicised Theravada being much less sensational (cf. Brunton 1934:117-18, 132-3). Nothing in Secret India can be accepted as the truth unless corroborated by other sources. The vaunted colonial esoteric expert was very unreliable (in contrast, Fletcher did commit himself to a monastic discipline, unusual in such circles).

The foil to Brunton’s deception is found in another account of his first visit to Ramana. This relevant alternative identifies the companion as Fletcher, who founded “the English Ashrama in Rangoon.” The key report was published, in September 1931, by the Peace magazine of Swami Onkar’s Shanti Ashrama in Andhra (Friesen 2005:22-24). That was three years before the innovative Secret India appeared.

The supposed academic status of Dr. Paul Brunton has often been used to deflect criticism. The reality is not flattering. In 1938, he obtained a correspondence degree from a fraudulent diploma business in America created by McKinley-Roosevelt Incorporated. This enterprise was subject to government proscription, leading to closure in 1947. Brunton’s spurious “doctoral degree” has no academic relevance whatever, being part of the commercial fantasy he projected. Many thousands of readers were deceived (including those at Ramanashram, or Ramanasramam). Brunton’s publisher Rider was tireless in broadcasting the impressive credential of Ph.D.

Ramana remained silent when introduced to Brunton and Fletcher (alias Subramanya) in 1931. Deceptions were created by Secret India. The suspect account of Brunton is embellished. “We have every reason to distrust what Brunton says, since he has admitted that he was only using Ramana for his preconceived ideas” (Friesen 2005:25). Another factor is urged:

Not only did Brunton interpret Ramana through his previous Theosophical ideas, but he in turn influenced Ramana and his disciples to interpret the [Advaita] experience in the same way. (Friesen 2005:46)

Brunton gave the impression that he achieved an enlightenment at Ramanasramam. His subsequent books do not confirm his pretension. He continued to be fascinated by occult powers or siddhis. His Search in Secret Egypt (1936) is a bizarre showcase of British neo-Theosophical speculation. For instance, Brunton believed that spiritual adepts from ancient Egypt were still alive in their tombs via a fully conscious trance. He also evidently believed that occult masters with great powers existed in the Himalayas, an influential theme of Blavatsky. The Irani mystic Meher Baba (1894-1969) repudiated this theory in a conversation with Brunton: “You will find nothing but dust and stones in their supposed abodes” (Brunton 1934:60). This denial was probably one reason for Brunton’s hostility to the Irani in Secret India. Certainly, Meher Baba was wrongly depicted by the occultist as having a receding forehead indicative of deficient thinking (ibid:48).

Brunton became notorious as a plagiarist of Ramana. He was banned from Ramanasramam in March 1939, by the managerial brother of the Advaita sage, who resented the fact that Brunton had copied so many sayings of Ramana as his own. An elementary factor should be grasped: “Brunton’s philosophy is not nondual” (Friesen 2005:84). Brunton was a stranger to Advaita, a teaching he confused with Yogic powers.

The British occultist was evidently proud of his ESP achievements. He even stated, in a book, that he sent telepathic messages, instead of written replies, to some letters he received (Brunton 1937:65). He evidently believed that he surpassed Ramana, expressing a public criticism of the Tamil sage in his book The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga (1941). Brunton had now transcended Yoga and Ramana in his speculations on the Overself, a favoured term that was not a translation from Sanskrit. Brunton apparently derived this new European (and American) word from a 1932 book by Gottfried de Purucker, a leader of the Theosophical Society who was here expounding The Secret Doctrine of Madame Blavatsky (Friesen 2005:7-8).

Brunton’s book Wisdom of the Overself (1943), gaining several reprints, was one of those to display the credential of Ph.D. on the title page. He claimed that “hundreds of texts were examined in the effort to trace and collate basic ideas.” Another description used by the author reads: “An exposition in such an ultra-modern form was until now quite non-existent.” Brunton even writes: “It would have been more self-flattering to parade the breadth of my learning by peppering both volumes with a thousand Sanskrit, Tibetan and Chinese quotations, names or words” (Brunton 1943:7ff; cf. Shepherd 1988:173-4). The phraseology could imply that Brunton was familiar with these languages.

A subsequent critic, Dr. Jeffrey Masson (having a Ph.D. in Sanskrit from Harvard), revealed that the bogus academic Brunton had no knowledge of Sanskrit or other Eastern languages. “He could not read the alphabet, any Indian alphabet, nor a single sentence in Sanskrit…. He was completely ignorant of the language” (Masson 1993:162). Many years later, in 1967, the occultist fraud was forlornly attempting to deceive a private gathering with his ruse of causing a heavy oak table to levitate. Brunton “was now nothing more than a charlatan, reduced to attempting carnival tricks for what he hoped would be a gullible audience” (Masson 1993:165).

Bibliography

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

——–A Search in Secret Egypt (London: Rider, 1936).

——–A Hermit in the Himalayas (London: Rider, 1937).

——–The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga (London: Rider, 1941).

——–The Wisdom of the Overself (London: Rider, 1943).

Chadwick, A. W., A Sadhu’s Reminiscences of Ramana Maharshi (1961; Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramanasramam, 1994).

Friesen, J. Glenn, Paul Brunton and Ramana Maharshi (2005).

——–Ramana Maharshi: Hindu and Non-Hindu Interpretations of a Jivanmukta (2006, online).

Godman, David, ed., Be As You Are: The Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi (1985; Penguin, 1988).

——–An Introduction to Sri Ramana’s Life and Teachings.

Masson, Jeffrey, My Father’s Guru (London: HarperCollins, 1993).

Narasimhaswami, B. V., Self Realization: Life and Teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi (1931; fourth edn, Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramanasramam, 2002).

Osborne, Arthur, Ramana Maharshi and the Path of Self-Knowledge (London: Rider, 1954).

Osborne, Arthur, ed., Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi (London: Rider, 1959).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

——–Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2004).

Venkataramiah, Munagala, Talks with Sri Ramana Maharshi (1955; Tiruvannamalai: Sri Ramanasramam, 2003).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

December 24th 2010 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 35

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.