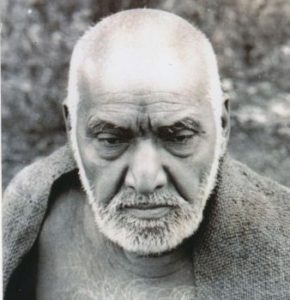

Upasani Maharaj

Upasani Maharaj (1870-1941), also known as Upasani Baba, was a brahman ascetic of Maharashtra, gaining the repute of a satpurusha. He is little known by comparison with popular gurus who have since flooded global media and markets. Nevertheless, the difference between his example and the sequels is potentially instructive.

Born at Satana, his grandfather was a pundit learned in Sanskrit texts. Upasani himself did not opt for the pundit career, instead choosing the role of an Ayurvedic doctor at Amraoti. After ten years as a vaidh, he moved north to Gwalior, intending to improve his finances as an estate owner. This plan crashed as a consequence of unforeseen complications. He afterwards removed himself from mundane pursuits. At Omkareshwar, he contracted a severe breathing problem, the precise cause now difficult to confirm. The Yogic practice of pranayama is partially implied in this setback.

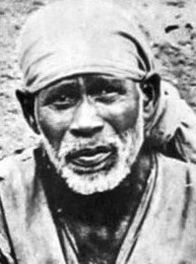

The complex train of events led him to Shirdi, where he encountered the faqir Sai Baba (d.1918), who lived in a rural mosque. The Muslim identity of Sai Baba initially repelled Upasani, a strict brahman elitist in religious outlook. His subsequent phase of discipleship under Sai Baba is frequently misrepresented, as a consequence of misunderstandings and sectarian fervour on the part of B. V. Narasimhaswami, a sannyasin from Madras who appeared on the scene many years later.

At the Khandoba temple in Shirdi, Upasani became indifferent to scorpions and snakes. He experienced a state of unmatta, a form of acute introversion in which he made no response to external events. This state became intermittent, permitting him to accomplish manual work which assisted his physical ballast. He was nevertheless considered crazy by local opponents, meaning devotees who resented his close link with Sai Baba.

In 1914, the temple dweller departed for a time to other places, including Kharagpur, in West Bengal. There he became a focus for devotees in a very unusual setting. He lived for months in a bhangi colony, inhabited by Dalit sweepers and scavengers. He assisted these people in various ways, performing much menial work. Eventually, conservative opposition caused him to depart from Kharagpur. High caste hatred of suppressed Dalits was (and is) an ugly feature of Hindu society.

When Upasani returned to Shirdi on later visits, he was becoming famous, a factor of increasing concern to zealous devotees of Sai Baba. The facts were squashed and eliminated in well known devotee accounts. Neglected reports restore the balance.

In 1918, at the village of Sakori, Upasani selected a local cremation ground as his home. At first, there was no accommodation for visitors in this bleak location. Subsequently, an ashram began to form. In 1922, he resorted to confinement in a bamboo cage. He remained completely unwesternised. The spartan existence of Upasani Maharaj contrasts with the comfortable ambience preferred by more recent Indian gurus of commercial orientation. Upasani wore sackcloth, not an ochre robe, nor an opulent gown in the Rajneesh style.

During the 1930s, he established at Sakori the Kanya Kumari Sthan. This distinctive community comprised kanyas or nuns, including Godavari Mataji (d.1990). The project was resisted by brahmanical orthodoxy, who customarily curtailed the activity of women and denied them the attainment of spirituality. Upasani Maharaj survived court cases launched by detractors, emerging as the victor. In 1935, his opponents were set at nought by a high court judge of Ahmednagar.

The Sakori nuns eventually achieved widespread respect from Poona to Varanasi. Upasani commenced their education in Sanskrit and ritual. After his death, the Kanya Kumari Sthan exercised a unique role, also being discernible as the inspiration for a much later trend of Hindu female priests gaining nationwide acceptance.

Meanwhile, the popular British occultist Paul Brunton (1898-1981) was contradicted by events which he omitted from a suspect travelogue (Shepherd 1988:146-176). He misconceived Upasani in a book entitled A Search in Secret India (1934), via a brief passage invoking a Parsi sceptic. Brunton associated the Hindu ascetic with the Bombay Stock Exchange and a Parsi speculator (Brunton 1934:63). Upasani was totally indifferent to the financial desires of those Indians trapped in the Western obsession with monetary gain. Many readers of Brunton had no idea what really happened in “secret India,” a commercial phrase of compromised factual relevance.

Bibliography

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

Narasimhaswami, B. V., Life of Sai Baba (4 vols, Mylapore, Chennai: All India Sai Samaj, 1955-56).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Gurus Rediscovered: Biographies of Sai Baba of Shirdi and Upasni Maharaj of Sakori (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1986).

———Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

———Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (New Delhi: Sterling, 2015).

———Sai Baba: Faqir of Shirdi (New Delhi: Sterling, 2017).

———Upasani Maharaj, Radical Rishi Biography (in four parts, 2020, online)

Tipnis, S . N., Contribution of Upasani Baba to Indian Culture (Sakuri: Shri Upasani Kanya Kumari Sthan, 1966).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 77

Copyright © 2020 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

Shirdi Sai Baba

Shirdi Sai Baba