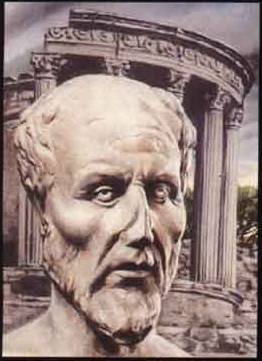

Representation of Plotinus

A biography of Plotinus was composed by his disciple Porphyry many years after his death. The famous Vita Plotini (Life of Plotinus) is regarded as a basically reliable report; some hagiology may have infiltrated. Porphyry was also the redactor of the Enneads, representing the formerly secretive writings of Plotinus.

His date of birth is uncertain, and likewise his racial origin. Plotinus would not refer to his early years, nor allow his birthday to be celebrated. As a consequence, the date and place of his birth passed into obscurity. His world-renouncing outlook was basically a mystery to commentators like Bertrand Russell. The “moderate ascetic” orientation of Plotinus decodes to a gulf between him and most modern commentators, including even Pierre Hadot.

When Ammonius died circa 242 CE, Plotinus had been his pupil for a decade. The latter departed from Alexandria in 243, joining an ill-fated expedition (possibly as a court philosopher) of the Roman emperor Gordian III against the Persians. Gordian was murdered in Mesopotamia by rebellious soldiers; this situation was part of the political problem afflicting Rome. Plotinus fled to Antioch, subsequently moving on to Rome by 245. There he settled, gaining followers in senatorial ranks. Plotinus eventually became well known. He maintained a cautious tactic of guarding his unpublished manuscripts, which were available only to committed students like Amelius and Porphyry. His circle were cosmopolitan, including Syrians, Alexandrians, and at least one Arab. Also, three women are fleetingly mentioned, two of them apparently Romans.

Plotinus disliked the rhetoric favoured by orators. He also detoured the set speeches maintained by Platonist convention, preferring an informal procedure involving the discussion of texts. He did not claim originality in his version of Plato. However, the Enneads are clearly innovative in a number of respects.

He endorsed study of the sciences, in a Platonist manner. He was evidently familiar with geometry, mechanics, optics, and music (then regarded as a science). Plotinus would not himself practise those pursuits, which he viewed as a secondary support for training the mind. In the Neoplatonist view, too much attention given to scientific activity is a distraction from the philosophical quest. There are differences with Aristotle, an authority whom Plotinus frequently contested. Some elements of convergence are also evident. In another direction, “the writings of Plotinus apparently contain strong repudiation of Stoic doctrines, as well as tacit acceptance of some of them” (Graeser 1972:xiii).

He is noted for opposing astrology, regarding horoscopy as deceptive. Plotinus taught freewill as distinct from determinism. His objective was to live in accordance with the standards of “virtue,” a complex theme associated with his elevation of the “Divine Mind” or Intellect. The strongly mystical element in his teaching emphasised a purification and illumination far removed from the convenient routines of orators and pedants. Plotinus contested the persuasions of Diophanes, an orator in Rome who favoured pederasty.

“We must break away towards the High,” was a Plotinian theme. Then as now, such emphases were unwelcome in many directions. A wealthy Roman pupil of Plotinus was Rogatianus, who declined the office of praetor pressed upon him by the Senate. The pupil renounced all his property and set free all his slaves. Under the influence of Plotinus, Rogatianus chose a simple lifestyle forsaking all social status and elitism.

Plotinus was opposed to the excessive wealth and slavery in the Roman environment, trappings which accompanied military prowess. One may conclude that he scored over Aristotle, who had endorsed slavery in a conciliatory gesture to the ruling class. Science might do little to remove social problems, whereas diligent mysticism may move a lot further.

Plotinus gained a reputation for austerity. Amongst his admirers were the Roman Emperor Gallienus and his wife Salonina. Gallienus was an intellectual type, with a taste for Greek culture; he was not popular with military commanders, despite his victories in battle. Plotinus advised that Gallienus should rebuild a ruined city in Campania, one that should be renamed Platonopolis, and accordingly governed according to the laws of Plato. This proposal was opposed at court, probably by the military. The details are vestigial.

The treatise entitled Against the Gnostics (Ennead II.9) is a well known feature of the Enneads. The protest was made on grounds of Platonist tradition, reason, and morality. The Gnostics were present in Rome; there are implications of flawed doctrines and behaviour. Gnostics were claiming a secret knowledge facilitating a short and easy path to the Divine. Plotinus contrasted this with the long, difficult, and necessary route involved in the Platonist practice of virtue and the due exercise of philosophic intelligence. He repudiated a resort to magic and ritual in the popular Gnostic sector, usages amounting to theurgy (theourgia).

Gnosticism, like Platonism, was a variegated phenomenon, one causing extensive confusions in the modern day. Popular Gnosticism rivalled both Platonism and orthodox Christianity. Gnostic adherents were spread throughout different countries, with diverse figureheads in the vista of “ascetics and libertines” discussed by scholars. Plotinus himself has some similarities to the ascetic wing; he claimed a “mystical union” in his version of philosophic rationalism. These subtleties are difficult to convey in the current climate of misconception caused by “new age” thinking, which includes the disputed integralism.

At the end of his life, Plotinus suffered a severe illness in the onset of an epidemic created by war and social unrest. The distinctive Emperor Gallienus was assassinated by military schemers. A mood of anarchy was prevalent, Rome was beset by troubles. Plotinus retired from Rome to the countryside, possibly afflicted with leprosy, stoically awaiting his end. The man who had rejected his birthday could also transcend death.

Bibliography

Armstrong, A. H. ed. and trans., Plotinus (7 vols, Harvard University Press, 1966-88).

——–“Plotinus” (195-268), in The Cambridge History of Later Greek and Early Medieval Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1967).

Gerson, Lloyd P., ed., The Cambridge Companion to Plotinus (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Graeser, Andreas, Plotinus and the Stoics: A Preliminary Study (Leiden: Brill, 1972).

Hadot, Pierre, Plotinus or the Simplicity of Vision, trans. M. Chase (University of Chicago Press, 1993).

MacKenna, Stephen, trans., The Enneads, ed. John Dillon (London: Penguin, 1991).

Narbonne, Jean-Marc, Plotinus in Dialogue with the Gnostics (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

Rist, J. M., Plotinus: The Road to Reality (Cambridge University Press, 1967).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 42

Copyright © 2011 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.