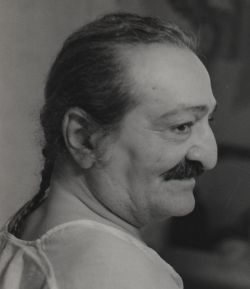

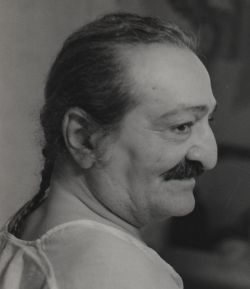

Meher Baba 1957

Meher Baba 1957Errors of assessment are a common occurrence in the contemporary field of “new religious movements.” Such matters necessitate due information rather than hearsay and assumption. The historical angle is necessary with the subject of Meher Baba (1894-1969), as with other figureheads of well known religious movements. The alternative is lore.

The Wikipedia lore interpreted a Hindu disciple of Meher Baba as being a rival “spiritual teacher” to the Irani mystic. No contextual information was supplied, only a variant of anecdotal calumny sustained for decades. The Hindu disciple and scientist was never a rival of Meher Baba, instead being a regular donor to the latter’s Meherazad ashram, located in Maharashtra.

The Hindu disciple lived for ten years in England at the instruction of Meher Baba. Possessing a degree in physics, this man worked as a salaried professional. As a consequence, he was able to send to India regular donations, amounting in total to thousands of pounds sterling. His level of commitment was very high, far more so than most other adherents of Meher Baba.

The experiences and viewpoint of this Hindu disciple are not without an interest of their own. However, obscuring biases of the Myrtle Beach Centre worked against any accurate knowledge of the subject. Instead of registering complaints and explanations provided in a former lengthy document, the prestige Centre ignored the document and opted to impose an unofficial ban on a book about Meher Baba that was published in 1988. As a consequence of this censorship, the stories about a rival spiritual teacher continued. Nor was there any rectification of other serious errors involved in the misrepresentation.

The literature on cults is now prodigious. Two of the basic problems, typical of “cults,” are misrepresentation and suppression of relevant details. The American branch of the Meher Baba movement achieved both of these undesirable drawbacks. An extension of this muddle infiltrated Wikipedia, a web venue notorious for troll activity and other complications. The rather basic sectarian issue is obvious to a number of observers.

Pseudonymous Wikipedia supporters of Meher Baba were keen to elevate a lengthy work entitled Lord Meher, presenting this as reliable fact eclipsing any other version, and more especially, my own book Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal. In the devotee presentation, an outsider book could only amount to deficient opinion as compared with the surpassing authenticity of a canonical work. Indeed, Meher Baba trolls were known to appear at different Wikipedia articles with the intention of removing non-canonical content. This action occurred even in an instance relating to transcription of antique Zoroastrian history (the Kaivan school), of which they knew nothing whatever. These people also disdained reference to a valid source in the canonical Meher Baba literature, preferring instead an inaccurate passage in Lord Meher.

My book included an unprecedented critique of the two major detractors of Meher Baba, primarily Paul Brunton. The latter’s book, A Search in Secret India, is still influential after eighty years of circulation. However, my critique (based on factual sources) was early ignored by the Myrtle Beach Centre, and many years later, was merely opinion according to devotee assessment. The hostile party on Wikipedia was unintentionally validating the travesty of Brunton’s deviation. Trolls do not read books, but merely debunk them in convenient online graffiti of two or three lines, in this instance supporting ideology of the Meher Baba Centres about canonical works.

The storytelling of Paul Brunton was here effectively justified by the ideological reflex. I had proved that Brunton’s hostile report of Meher Baba was unreliable, a factor which serious readers recognised (including some Brunton partisans). However, my substantial critique of Brunton, in Wikipedia troll assessment, amounted to the mere opinion of an outsider to the infallible canon extolled by the Meher Baba movement. This episode cannot be disregarded, because the troll action was closely linked, via editorship, with the Meher Baba article on Wikipedia.

The multi-volume Lord Meher has seldom been duly analysed. An extensive editorial process was involved. A relatively minor consideration is that Bhau Kalchuri was not the sole author of this work, despite the contrary impression conveyed for over thirty years by devotee media. The Reiter edition of twenty volumes, on all the title pages, presented Kalchuri as the sole author. Feram Workingboxwala was very unpopular, while the American editor and compiler David Fenster was in low profile for many years.

Lord Meher does not contain due information about the misrepresented Hindu disciple and donor who lived in England until 1964. This work is not comprehensive, despite the length. A number of passages in Lord Meher identify the followers of Meher Baba as “lovers.”

During the mid-1960s, I attended meetings of the London group of Meher Baba supporters. At that time, the subscribers did not refer to themselves as “lovers” of Meher Baba. This identity tag did not become prevalent until 1967, being favoured by the new generation of devotees associated with Pete Townshend and the American influx. The rather more conservative and vintage British devotees called themselves the “friends of Meher Baba.” Although Meher Baba himself used the (mystical) word “lover,” he did not stipulate that his followers should describe themselves in this manner.

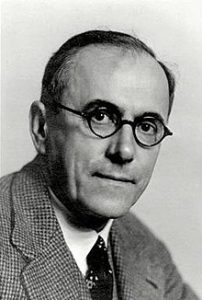

Charles Purdom

A representative of the older trend was author Charles Purdom (d.1965), a figure in reaction to some devotee tendencies. Purdom achieved a degree of objectivity that is comparatively rare in religious movements. It would not be fair to place him in the same category as the trolls and storytellers of the Meher Baba movement.

Purdom’s preface to his book The God-Man (1964) does not mention the word avatar. The author here says that he has done his best “to maintain the necessary degree of detachment of mind.” Compared with other partisan recommendations, the appraisal of Meher Baba by Charles Purdom is restrained:

I do not think one can find any parallel in modern times with the life of this simple, subtle, innocent, unpredictable, alarming and engrossing man. (Preface, unpaginated)

Over the years, I have found that devotionalism is a distorting factor in relation to the record of Meher Baba. For instance, the attendant dogmatic approach obliterated details of the abovementioned Hindu donor and certain other entities, including myself. I decline to be eliminated by the dogmatists, and will resist misinformation. Democracy is a farce at places like the Myrtle Beach Centre, where a process of suppression has been operative for many years.

My interest in Meher Baba applies to ascertaining historical dimensions of his biography, as distinct from the lore and confusion that is too frequently found. I have no interest in promoting exclusivist avatar themes, which evidently encourage some devotees to adopt a status profile as followers of Avatar Meher Baba. I have no interest in promoting “lover” clichés, these also being objectionable in acts of misrepresentation and suppression. The vaunted love can easily become hate campaign.

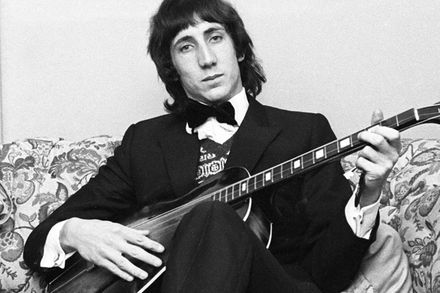

Pete Townshend

The phase of ascendancy achieved by Pete Townshend, during the 1970s, is perhaps instructive. That rock star became the focus of adulation for numerous new “Baba lovers” in different countries. He has since admitted the limitation of his self-appointed role as a leader and organiser within the Meher Baba movement. Townshend has been honest in a number of ways, a refreshing contrast with troll activities presuming an unassailable spokesmanship for Meher Baba. Townshend’s own reflection, found at his website, is relevant here:

What was clear to me in early 1980 was that I could no longer stand as any kind of public representative for Meher Baba with such recent alcohol and drug-abuse problems. Meher Baba Oceanic, the pilgrim centre I had run, had in any case slowed down to a crawl while I descended into self-obsession. Several of my employees there had gone through problems of their own, and some time in 1982 I impolitely sacked everyone.

These references indicate serious problems. Townshend nearly killed himself on alcohol and drugs. Yet he had been exalted by many devotees even before he created, in 1976, the ill-fated centre known as Meher Baba Oceanic. Townshend was initially influenced by Purdom’s book The God-Man (1964), and describes the author as “an eminent British journalist of the Thirties” (Who I Am, p. 110). That is a contraction of identity, because Purdom was also a garden city pioneer and author, and still leading the London group of “friends” in 1965, only two years before the new wave appeared. Townshend and other “lovers” reversed the sober approach of Purdom into cliché, guitar music, and devotee poetry.

The new wave of “lovers” were frequently afflicted by proximity to the drug infraculture, so pervasive in Western countries since the 1960s. In America, many of them were content with such slogans as “Don’t worry be happy.” This theme comprised an acute reductionism, not reflecting Meher Baba’s rather distinctive metaphysical teaching. The happy lovers were averse to complexity.

An eccentric rune of the Townshend era was “Baba’s love game.” The rock star and his colleagues were viewed by their own camp as avant-garde representatives of the unique Avatar. Townshend acknowledged the American inspiration of Murshida Ivy Duce, leader of Sufism Reoriented. He was perhaps influenced more by Adi K. Irani (d.1980), the former secretary of Meher Baba, who had gained a limelight role as exegete of the Avataric cause. The love game ended with Townshend’s addiction to large quantities of brandy, accompanied by an afflicting ingestion of cocaine and heroin. His version of “Baba’s Umbrella” was not waterproof.

A major influence, upon the new wave of Baba lovers, were newsletters dating to the 1960s. These were composed by Mani, the sister of Meher Baba who lived at Meherazad ashram. Mani S. Irani (d.1996) favoured an influential vocabulary of “lovers” and the “Beloved.” The newsletters were regarded as canonical texts at Meher Baba Centres. However, a literary critic said that these writings were gushing and sentimental, not profound. Even some of the happy lovers were worrying that insufficient information about Meher Baba was being conveyed by Mani. They were puzzled to find frequent descriptions of secondary matters. Apologists excused Mani by saying that she was not allowed to describe more about Baba, who was in seclusion. Mani did relay messages from, and some details about, the figurehead. However, there are distinct gaps in coverage.

Insofar as some basic events were concerned, the Mani “family letters” amounted to a detour. For instance, a more recent and lengthy account of 1960s events provided descriptions very different to those of Mani, including details of how Meher Baba strongly rebuked argumentative mandali, including Mani herself (Kalchuri Fenster 2009). The disparity is too revealing to ignore. Essential traits and methods of Meher Baba (silent since 1925) remained obscure, overlaid by preferences of the far more vocal lovers.

Bibliography:

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

Irani, Mani S., 82 Family Letters (Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Press, 1976).

B. Kalchuri, F. Workingboxwala, D. Fenster et al, Lord Meher (Reiter edn, 20 vols, 1986-2001).

Kalchuri Fenster, Sheela, Growing up with God (Ahmednagar: Meher Nazar, 2009).

Parks, Ward, ed., Meher Baba’s Early Messages to the West (North Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Foundation, 2009).

Purdom, Charles B., Life Over Again (London: Dent, 1951).

——–The God-Man (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964).

Shepherd, K. R. D., Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

———Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

Townshend, Pete, Who I Am (London: HarperCollins, 2012).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 66

Copyright © 2015 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

Meher Baba 1957

Meher Baba 1957