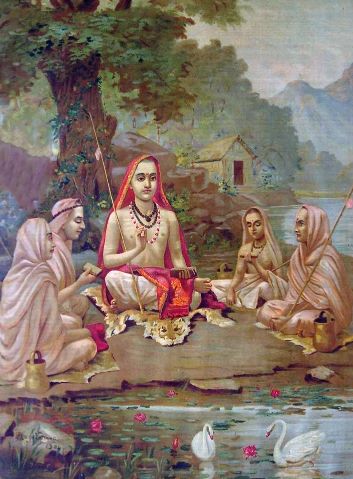

Shankara with disciples, by Raja Ravi Varma (1904)

Advaita Vedanta signifies an Indian philosophy of “non-dualism.” A major exponent was Shankara, of whom very little is reliably known. The investigator has to negotiate hagiographies composed many centuries after the death of this figure. His life is not easy to chart, to say the least, despite conventional depictions that do not question details. The dates of Shankara are sometimes given as 788-820 CE, but this is not definitive. One alternative has been suggested in terms of ranging between 650 and 775 CE (Pande 1994:52). A member of the brahman caste, Shankara was reputedly born at a village in Kerala.

We may believe that he became a renunciate at an early age. Tradition credits Shankara with establishing a monastic organisation. This is known as the Shankara Order. Over the centuries, major monasteries featured abbots bearing the title of Shankaracharya. The Shringeri monastery (in Karnataka) is one of these far-flung centres, gaining the repute of being the first monastery founded by Shankara. This claim has been contradicted by the historical evidence for Shringeri as a centre of Jainism until the fourteenth century (Kulke 1985). At this juncture, Hindu patronage from the kingdom of Vijayanagara was influential. Shringeri emerged as a centre of Shaivism. Land was donated by Hindu monarchs for the purpose of attracting brahmans to that location.

In the traditional version of his life, Shankara is said to have established the group of Shaiva renouncers known as Dashanami sannyasins (and nagas). This contingent, strongly associated with the Shankara Order, gained a militant complexion. A counter-suggestion argues for the late sixteenth/early seventeenth century as a much more probable date of their formation (Clark 2006 and 2016). Mercenary armies of naga (naked) sannyasins were generally recruited from the lower castes.

Traditional ascriptions are reflected in such coverages as: “During his lifetime he [Shankara] managed to compose more than 400 works of various genres and to travel throughout nearly all of South India, edifying disciples and disputing opponents. It is Shankara’s preaching and philosophic activity that, in the eyes of orthodox tradition, accounts for the ultimate ousting of Buddhism from India” (Isayeva 1993:2).

Legendary biographies of Shankara date from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. “Although they have certain broad similarities, they have numerous contradictions in detail, and they are full of miracles and exaggerations” (Pande 1994:4). The accounts vary markedly in relation to diverse journeys, pilgrimages, debates, and the founding of monastic centres (ibid:32). Shankara became celebrated as an incarnation of Shiva, a development of uncertain date. Shankara hagiography involved “the mythical pattern of divine incarnation, disputation with rival sects and schools, the establishment of new temples and monastic centres of worship, and the synthesis of Smarta-Puranic cults under the aegis of Advaita” (ibid:19-20).

Hundreds of works are attributed to Shankara. However, most of these are now thought to have been composed by much later monastic leaders bearing the title of Shankaracharya. Paul Hacker and other scholars have taken a duly critical approach. The fact is that only a small number of Advaita texts can safely be regarded as the output of Shankara himself. In this respect, the basic work is a lengthy commentary (bhashya) on the Vedantic Brahma Sutra. Famous later compositions (even Vivekachudamani) are rejected by some analysts as spurious. Such popular texts were influential in shaping the Advaita doctrine, which developed over a long period of time.

In his commentary known as Brahma Sutra Bhashya, Shankara was in strong opposition to Buddhism and the Purva Mimamsa tradition of Hinduism. He was concerned with the correct interpretation of Vedic scripture, in which direction he sought to reveal opposing views as errors.

Shankara argued against the ritualism of Mimamsaka exponents. He supported a version of religion associated with the Upanishads or jnana-kanda. An Advaita priority was discrimination (viveka) between the real and the false. Whereas ritual priests elaborated a belief system based on merits derived from Vedic ceremonies, which supposedly led to heaven. Shankara emphasised the attainment of self-knowledge, meaning knowledge (jnana) of the atman.

The Vedantic doctrine of maya (illusion) has excited varying responses, including denial. Renouncers or sannyasins viewed the householder ritualist lifestyle as being bound by maya. The sannyasin sought freedom through knowledge of the atman (a term variously translated). The various texts do not satisfactorily explain how the self-knowledge is achieved. The mere affirmation of Upanishadic slogans like Tat tvam asi (You are That) is not the most convincing rationale. This famous phrase is found in some Shankara texts, along with modifications.

Absolute liberation does not arise when one is told, ‘Thou art That.’ One should, therefore, have recourse to the reiteration (of the idea, ‘I am Brahman’) and support it with reasoning. (Upadeshasahasri, trans. Jagadananda 1961:207)

“The Brahma Sutra has actually become the basis upon which we learn the philosophical thought of the early Vedanta school. Since, however, the style of this work is concise to a fault, omissions in it are many and to interpret the text is not at all easy” (Nakamura 1983:425). The brevity is pronounced. “Each sutra usually consists of two to ten words at the most, and it is rare to find one that is longer” (ibid:440).

Shankara contributed an Advaitic interpretation of the Brahma Sutra. A discrepancy requires attention. “The theory of absolute identity of the individual self and Brahman, taught by Shankara, is contrary to the thought of the Brahma-sutra itself” (ibid:427). Paul Deussen and other scholars tended to conflate the two interpretations, leading to some confusion (e.g., Deussen 1912).

The early Vedanta was not a unified tradition of exegesis. “Scholars have frequently asserted that the thought of Shankara has the closest connection with the atman theory of Yajnavalkya in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad” (Nakamura 1983:430). The Brihadaranyaka is one of the earliest Upanishads, substantially antedating the Brahma Sutra, which may date to the fifth century CE in the extant form of that terse treatise.

The obscure author, or authors, of the Brahma Sutra, were defending the old Vedic religion against the Buddhists, Jainas, Sankhya rationalists, and others. “The evident preference of the authors of the Brahma Sutra was for the daily performance of the Vedic ritual to be maintained along with the meditations on more symbolic aspects of etiquette” (Shepherd 1995:642).

Shankara likewise sustained a contest with rival religious doctrines. However, he differed from the Brahma Sutra by contesting the ritualist mentality evident in that version of early Vedanta. He awarded a secondary status to Vedic texts depicting meditation on rituals (those texts referred to deities presiding over specific ceremonies).

Shankara’s classic Brahma Sutra Bhashya includes a critique of the Yoga and Sankhya systems of philosophy. However, Shankara is traditionally credited with a commentary on the Yoga Sutra. The anomaly has aroused differing explanations, including one which suggests that Shankara transited from the standpoint of a Yoga expositor to Advaita comprehension. Another interpretation denies the authorship of Shankara in relation to that commentary (Rukmani 2001).

“In his commentary on the Chandogya Upanishad (8.12.1), he [Shankara] refers to the Paramahamsa monks who transcended caste and ashrama in their pursuit of the non-dual knowledge. These ascetics are identified with the ‘true tradition’ which he says Gaudapada followed. For Shankara, they alone represented the ultimate level of truth” (Shepherd 1995:666). Shankara’s monastic ideal of the Paramahamsa involved criteria of “actual spiritual attainment, not his formal membership of a social group” (Pande 1994:247).

The name of Gaudapada is inseparably associated with Shankara, as a predecessor. A distinctive early Advaitin, Gaudapada may have lived during the sixth century CE. He composed an unusual commentary on the Mandukya Upanishad, exhibiting a familiarity with Mahayana thought associated with exponents like Nagarjuna and Asanga (Nakamura 1983:51). The fourth chapter is rich in Madhyamaka and Yogachara terminology, prompting a suggestion of authorship by another writer (King 1995).

Unlike the authors of the Brahma Sutras, Gaudapada insists very strongly on the illusory or phenomenal character of the world, and claims that in this he is only following an earlier tradition for the interpretation of the Upanishadic texts. The existence of earlier followers of the Upanishads who held this view is confirmed by Bhartrhari, late fifth century…. Gaudapada says: ‘Those who are experts in the Upanishadic wisdom look upon this world as if it were a cloud-city seen in a dream.’ The sages who have gone beyond fear, attachment and anger have the direct experience of the truth of non-duality, in which all plurality and illusion vanishes. (Alston 1980:24-25)

Bibliography:

Alston, A. J., Samkara on the Absolute (London: Shanti Sadan, 1980).

Cenkner, William, A Tradition of Teachers: Shankara and the Jagadgurus Today (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983).

Clark, Matthew, The Dasanami Samnyasis: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order (Leiden: Brill, 2006).

——–“Religious Sects, Syncretism, and Claims of Antiquity: The Dashanami-Sannyasis and South Asian Sufis” in Raziuddin Aquil and David L. Curley, eds., Literary and Religious Practices in Medieval and Early Modern India (New York: Routledge 2016).

Cole, Colin A., Asparsa Yoga: A Study of Gaudapada’s mandukya karika (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 2004).

Deussen, Paul, Das System des Vedanta, 1883; The System of the Vedanta, trans. Charles Johnston (Chicago: Open Court, 1912).

Gambhirananda, Swami, trans., Brahma Sutra Bhasya of Shankaracharya (Calcutta: Advaita Ashrama, 1965).

Halbfass, Wilhelm, ed., Philology and Confrontation: Paul Hacker on Traditional and Modern Vedanta (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995).

Isayeva, Natalia, Shankara and Indian Philosophy (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993).

Jagadananda, Swami, trans., Upadeshasahasri of Sri Sankaracharya (third edn, Madras: Ramakrishna Math, 1961).

King, Richard, Early Advaita Vedanta: The Mahayana Context of the Gaudapadiya Karikas (State University of New York Press, 1995).

Kulke, Hermann, “Maharajas, Mahants and Historians: Reflections on the Historiography of Early Vijayanagara and Sringeri” (120-143) in A. L. Dallapiccola and S. Zingel-Ave Lallemant, eds., Vijayanagara, City and Empire: New Currents of Research (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1985).

Nakamura, Hajime, A History of Early Vedanta Philosophy, Parts 1 and 2 (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983-2004).

Nikhilananda, Swami, trans., The Mandukyopanishad with Gaudapada’s Karika and Sankara’s Commentary (third edn, Mysore: Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama, 1949).

Pande, G. C., Life and Thought of Sankaracarya (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994).

Potter, K. H., ed., Advaita Vedanta Up to Samkara and his Pupils (Princeton University Press, 1981).

Rukmani, T. S., text and trans., Yogasutrabhasyavivarana of Sankara (2 vols, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2001).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Minds and Sociocultures Vol. One: Zoroastrianism and the Indian Religions (Cambridge: Philosophical Press, 1995).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 70

Copyright © 2016 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

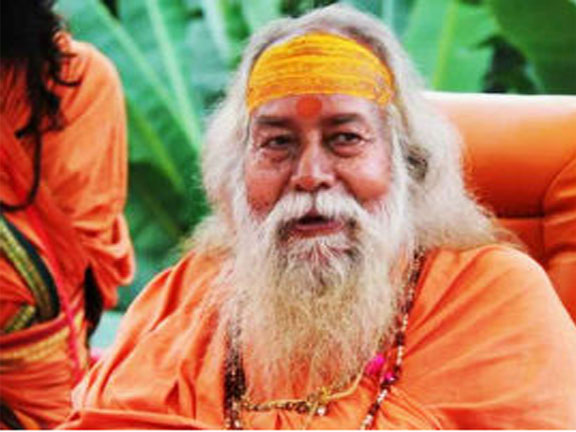

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati