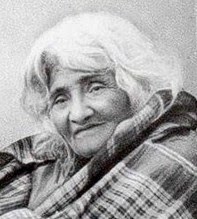

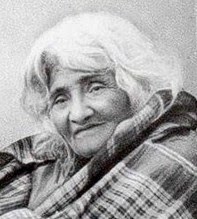

Hazrat Babajan

Hazrat BabajanHazrat Babajan (d.1931) was born in the Afghan territories at an unknown date. A Pathan (Pashtun), and a Sunni Muslim, she spoke Pashtu, Persian, and Urdu. Her early life transited from the purdah of an aristocratic milieu to the renunciate career of a faqir. Babajan lived in the Punjab for many years. She was reputedly buried alive by fundamentalists who objected to her ecstatic utterances, also to her public focus as a saint who received worship from local Hindu people.

Obscure journeys brought her south to Bombay, from where she undertook a pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca in 1903. When Babajan arrived back in India, she moved to Poona, a centre of the British Raj, where a military cantonment existed. She settled in Poona (Pune) by 1905.

Babajan at first lived as a street mendicant in Poona, afterwards staying near a mosque in the suburb of Rasta Peth. Here formed a nucleus of Muslim devotees. The vicinity of the mosque became crowded with her visitors. This was apparently the reason why she eventually moved on. At circa 1910, she settled permanently under a neem tree in Char Bawdi (Bavadi), on the outskirts of the cantonment.

She demonstrated a rigorous faqir lifestyle, refusing to keep money or other gifts, and declining to acquire possessions or live in comfort. She lived under the tree, sitting on the bare ground, exposed to all weathers. She would only consent to a simple awning made of gunny (sack) cloth. Unlike many other faqirs, Babajan was not an exhibitionist. She did not perform ascetic stunts. Although she is associated with a Sufi outlook, Babajan was not a member of any Sufi order. She did not teach any doctrine. Garbed in simple attire, she did not wear a veil.

Persons in this independent category (from official Sufism) were often called majzub. This Persian word generally signified God-absorption. Many different temperaments were represented; in this respect, the label of majzub is very much a blanket term.

The environment at Char Bawdi was initially semi-rural, the adjacent slum area featuring ramshackle buildings. Babajan’s presence strongly contributed to a major upgrading of the locale, which became increasingly urbanised. Motor traffic intensified after the First World War of 1914-18. This was a welcome development to the cantonment authorities. Babajan was the major focus of attention in the area, gaining hundreds of devotees by 1920. The British did not understand why a homeless faqir gained so much esteem.

Amongst the early Muslim visitors were Pathan soldiers (sepoys) from the cantonment barracks. They became her devotees, acting as bodyguards. The sepoys provided protection against the intrusion of drunkards and thieves, who at first congregated after nightfall in Char Bawdi. The interlopers soon dispersed. However, beggars were a frequent sight in the locality. The sepoys served and died in the First World War.

During her early years at Poona, orthodox parties could not understand the independent orientation of Babajan. Conservative Zoroastrians were disapproving of any departure from religious orthodoxy; the mere fact of her being a Muslim was cause for censure. Similarly, some Muslims were also very insular. Hostile Muslims and Zoroastrians initially tended to regard Babajan as a witch. The situation was potentially dangerous. At that period, women could be burnt as witches in rural India; old women (or widows) were particularly vulnerable. The fate of some women could be tragic, as in medieval Europe. Babajan had to endure stone-throwing from some families (apparently not Hindus). The sepoys were probably defensive on this account. The increasing number of her devotees meant that she could no longer be regarded as a “witch” by circa 1920.

The stone-throwers were children influenced by their parents. Muslim families apparently started this hostility, viewing Babajan as an eccentric nonconformist or even a witch. Belief in sorcery was certainly widespread in Islam, where magic is forbidden. Sorcerers and fortune tellers did exist amongst Muslims, but Babajan was not one of these. Talismans and amulets were popular accoutrements, missing in the case of Babajan.

The persecution of witches in India is now considered a form of lethal misogyny. Hinduism harbours extremist tendencies against the witch (dayan). A strong “evil eye” folklore revolves around the dakini, a female spirit believed to drink the blood of men (the dakini is associated with Shaivism, also Tantric Buddhist mythology). In parts of India (mainly Central India), grim occurrences are on recent record. Severe beatings and lynchings (and even beheadings) are not an attractive tourist feature. Low caste women are often the targets of this fanaticism. Indian police records have suggested that more than 150 women are killed every year as witches in the twenty-first century. The details can cause shock.

They are burned, hacked or bludgeoned to death, typically by mobs made up of their neighbours and, sometimes, their own relatives. Ritual humiliation often precedes death. (Witches are still hunted in India, The Economist, 21/10/2017)

Babajan was successful in her counter strategy to religious hate. Her memorable interactions with Zoroastrian women indicate a dimension of cross-cultural empathy quite alien to Eastern fundamentalists and white supremacists. The insular religious mentality was graphically demonstrated by an Irani Zoroastrian family of the 1920s, who hated both a Hindu guru and an Irani nonconformist (and also Babajan). The bias here employed a recourse to appropriate the money of a victimised relative, perhaps similar to cases of Hindu “witches” who are molested because they own desirable land. The urban victim at Bombay was Kaikhushru Masa Irani (d.1931). He and his wife Soonamasi were amongst the liberal Zoroastrians who amenably encountered Babajan at Char Bawdi.

The inter-religious nature of Babajan’s following is notable. The majority were Muslims, but Zoroastrians and Hindus were also in evidence. The most famous of the Zoroastrian contacts was Meher Baba (1894-1969), who first met Babajan in 1913, later forging an independent career in the Ahmednagar zone.

A minority of Hindu women became the equivalent of faith healers, using mantras and other techniques. Some Muslim male faqirs displayed elaborate healing rites that were evidently designed to impress their audience, converging with ostentatious “miracles” of Hindu holy men. The various types of healer generally received money for their services. Babajan was not in this category. Dr. Ghani briefly records that petitioners would approach her for a cure. She responded in an idiosyncratic manner, apparently obliging the sufferers by her “funny operation” of tweaking the “painful or diseased” portion of flesh (Ghani 1939:35-36). No money was requested, no mantras were employed. The frequency of such episodes is not on record. Other accounts have no reference to this feature of her interaction with visitors.

In the early 1920s, Babajan’s exposure to the weather was a matter of concern to devotees. They decided that a proper shelter must be constructed for her at the neem tree. The British at first resisted this incentive. The cantonment authorities wanted to move the faqir elsewhere, because her assemblies were tending to obstruct the traffic on an increasingly busy road. However, the Cantonment Board eventually reconsidered the matter; they conceded a new shelter at Raj expense. A drawback was that Babajan herself proved reluctant to accept the modification of her faqir lifestyle. She had to be persuaded to do so by devotees.

Despite her age, Babajan remained healthy. Her basic fitness was demonstrated in brisk walks that occurred frequently until her last years; sometimes she walked for miles across Poona. She disliked medicaments and drugs, which she avoided. Her diet was simple, including tea frequently offered by visitors. When devotees plied her with too much tea, she would give this away, as she did with everything else. Redistribution was a basic habit of hers, quite distinct from hoarding.

From about 1926, she was chauffeured in a motor car around the city. However, she often used a tonga or horse cab. In April 1928, she travelled outside Poona for the first time since she had arrived there. On that occasion, Babajan made an unexpected journey by car to Meherabad, the distant ashram of Meher Baba situated near Ahmednagar. No publicity was involved. Babajan afterwards repeated her visit (Shepherd 2014:89-90).

Such details are lacking in the well known book, by the British occultist Paul Brunton, entitled A Search in Secret India (1934). This provides a brief depiction of Babajan that is to some extent misleading (Shepherd 1988:148; Shepherd 2014:91-3, 94). Brunton conceded that “some deep psychological attainment really resides in the depths of her being” (Secret India, p. 64). However, the same writer misrepresented Meher Baba’s physiognomy. His account of that “messiah” entity is unreliable. Brunton later became known as a plagiarist of the Advaita Vedanta exponent Ramana Maharshi.

The ashram of Ramana Maharshi eventually turned against Brunton, despite the latter’s celebration of the former in Secret India. In a later book, The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga (1941), Brunton criticised Ramana as a self-absorbed mystic. The British writer also defensively asserted that he had already known about meditation and yoga before encountering Ramana. He subsequently resorted to the spurious academic credential of Dr. Paul Brunton, which is no proof of authority (the credential was derived from a correspondence course).

Hazrat Babajan had no doctrine anyone could steal. Her form of indirect tuition was concealed in asides to visitors and expressed in different languages. She sidestepped both Vedanta and institutional Sufism, neither of those traditions being favourable to women.

The commercial Secret India of Brunton was not the best guide to that country. The traveller briefly met Babajan in 1930, but needed an interpreter. Brunton’s commentary posed the theme of “a genuine faqueer [sic] with wondrous powers” (Secret India, p. 64). The would-be Yogi desired to find evidence of powers, which are considered a distraction by other parties.

Babajan did not claim powers. The only claim discernible is represented by her obscure ecstatic utterances implying an identity with the divine (Shepherd 2014:41-2). Such utterances, associated with her early years at Poona, were not in general well understood. Instead, some devotees chose to emphasise “miracles” attributed to her. The indications are that devotees, and other visitors, varied greatly in their assessment of events.

At the time of Babajan’s death, the press reported some popular beliefs: “It is claimed that she was 125 years of age, and the possessor of magical powers in addition to her powers of sight into the future” (“Poona’s Homage to Famous Muslim Woman Saint,” The Evening News of India, September 23rd, 1931). The historian can reckon more easily with the fact that her funeral was attended by thousands of Muslims and Hindus, and on a scale not formerly known in Poona. An extant newspaper photograph confirms the large number of people attending the procession of her coffin.

The shrine of Hazrat Babajan was constructed by Muslims at the neem tree in Char Bawdi. This monument has since been rebuilt, with Chishti Sufi associations attendant upon the annual celebrations.

Bibliography:

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

Ghani, Abdul, “Hazrat Babajan of Poona,” Meher Baba Journal (1939) 1 (4):29-39.

Kalchuri, Bhau, et al, Lord Meher Vol. 1 (Reiter edn, Myrtle Beach SC, 1986).

Purdom, Charles B., The Perfect Master: Life of Shri Meher Baba (London: Williams and Norgate, 1937).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., A Sufi Matriarch: Hazrat Babajan (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1986).

—— Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

—— Hazrat Babajan: A Pathan Sufi of Poona (New Delhi: Sterling, 2014).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

February 2014 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 59

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

Hazrat Babajan

Hazrat Babajan