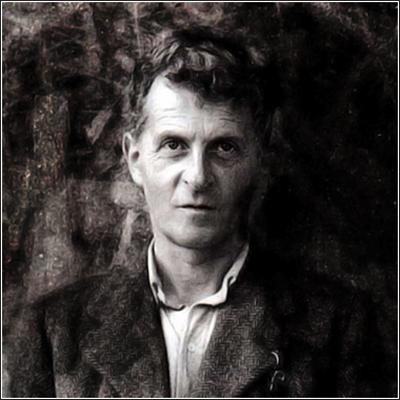

Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1947

Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1947

There are some very different interpretations of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). The Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) was an influential work receiving much commentary over the years. A key sentence of the Tractatus is well known. “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” Much depends upon what we really can speak about.

There is still no definitive or standard view of what the Tractatus means. Contrasting interpretations of this salient text can evoke irritation. The ambiguity discernible here perhaps underlines Wittgenstein’s own statement, made to his publishers, that what the Tractatus did not contain was more important than what it did contain. This paradox is sometimes interpreted in the context of a “metaphysical” dimension which Wittgenstein regarded as being beyond speech. While one version tends to interpret him as a sceptic, others find in him a strong religious streak of a nonconformist complexion.

“The idea that philosophy is not a doctrine, and hence should not be approached dogmatically, is one of the most important insights of the Tractatus” (Anat Biletzki, “Ludwig Wittgenstein,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). However, by 1931, the author was referring to his Tractatus as “dogmatic” (ibid).

Wittgenstein recognised deficiencies of the Tractatus in his later years. “It was above all [Piero] Sraffa’s acute and forceful criticism that compelled Wittgenstein to abandon his earlier views and set out upon new roads” (Von Wright 1958:15).

Another interpretation suggests that he was less discontented with the Tractatus in his mature years than is often believed. The crux here is that Wittgenstein was more dissatisfied with the assumptions he probed, not with his actual conclusions. The basic confrontation transpired to be with logical positivism. He examined the belief that an entirely empirical language is possible. Adherents of this explanation say that the Tractatus proved the positivist proposition about language to be untenable.

From this angle, his main point of disagreement was with what other philosophers made of the Tractatus, especially the Vienna Circle, who were enthusiastic about this work. Wittgenstein is said to have perceived that Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, Rudolf Carnap, and others did not fully understand the arguments involved. In this version, the flawed interpretation of the Tractatus, by the Vienna Circle, was the main reason for Wittgenstein’s return to Cambridge in 1929, likewise his subsequent application to the Philosophical Investigations (1953).

Wittgenstein wrote as though philosophy, prior to his time, amounted to a hopeless confusion. The traditional “problems of philosophy” were mere pseudo-problems arising from a lack of attention to the employment of language. How we use language is here the denominator. Language gains a monumental significance for Wittgenstein. “The limits of language are the limits of my world.” He restricted attention to the “language games,” a straitjacket which is not inevitable outside his worldview.

Some commentators explain the situation by claiming that Wittgenstein transited from logic to ordinary language in his rejection of dogmatism. He preferred an aphoristic style of composition to anything systematic.

Investigators have found a contradiction in Wittgenstein’s so-called “contemplative philosophy.” His form of verbalism avoided “metaphysical” identifications. However, he did at least once express a positive view about the conception of God. There are different commentarial statements about whether he actually believed in God. In theory, he should have remained silent about such beliefs, in accord with his austere discussion of language philosophy as represented in the Tractatus.

The memoir by Professor Norman Malcolm states: “Wittgenstein frequently said to me disparaging things about the Tractatus. I am sure, however, that he still regarded it as an important work” (Malcolm 1958:69).

Malcolm also penetrated the difficult subject of religion in this instance. Wittgenstein told Malcolm that he had been contemptuous of religion in his youth; at about the age of 21, a change occurred in him, when “for the first time he saw the possibility of religion” (ibid:70). Then during his service in the First World War, he was strongly influenced by Tolstoy’s writings on the Gospels (ibid). He nevertheless produced such an ostensibly “positivist” work as the Tractatus, from which Malcolm cites 6.44: “Not how the world is, is the mystical, but that it is.” Like other aphorisms of Wittgenstein, special interpretation is needed.

Wittgenstein was impatient with declared proofs of the existence of God. He disliked the writings of Cardinal Newman, “but revered the writings of St. Augustine” (Malcolm 1958:71). However, he cannot be called a Christian. The verdict of Malcolm was:

I believe that he looked on religion as a ‘form of life’ (to use an expression from the Investigations) in which he did not participate, but with which he was sympathetic and which greatly interested him. Those who did participate he respected – although here as elsewhere he had contempt for insincerity. I suspect that he regarded religious belief as based on qualities of character and will that he himself did not possess. (Malcolm, Memoir, p. 72)

Wittgenstein has been described as a tortured genius, subject to bouts of depression and suicidal tendency as a consequence of his homosexual disposition (Monk 1990). One interpretation is that he was ashamed of the disposition, from which he wanted to escape. He contrasts with the more suave and socialising heterosexual figure of Bertrand Russell (1872-1970), his former tutor who became a figurehead of the radical liberalism gaining popularity at the end of Russell’s long life. Both of these entities can be criticised for lifestyle problems without denying their intellectual merits.

To his credit, Wittgenstein evidently believed that philosophy is useless unless facilitating a morally superior lifestyle. To him, the routine profession of philosophy amounted to a “living death.” This perspective contradicts the status profile frequently awarded that profession elsewhere. His reaction to British Empire academic philosophy is memorable. He exhorted his students to apply themselves to a practical pursuit, such as medicine or manual labour, implying this to be the best resort if they were serious about philosophy.

Bibliography

Malcolm, Norman, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir (Oxford University Press, 1958).

McGuinness, Brian, ed., Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911-1951 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995; second edn, 2008).

McNally, Thomas, Wittgenstein and the Philosophy of Language: The Legacy of the Philosophical Investigations (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Monk, Ray, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius (London: Jonathan Cape, 1990).

——–Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness (London: Jonathan Cape, 2000).

Oskari, Kuusela, and Marie McGinn, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Wittgenstein (Oxford University Press, 2011).

Sullivan, Peter, and Michael Potter, eds., Wittgenstein’s Tractatus: History and Interpretation (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Von Wright, G. H., “Biographical Sketch,” in Malcolm, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir (Oxford University Press, 1958).

Von Wright, G. H., and Friedrich Waismann, Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle (Oxford: Blackwell, 1979).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness (London: Routledge, 1961).

——–Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Blackwell, 1963).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

January 11th 2010, modified 2021

ENTRY no. 8

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.