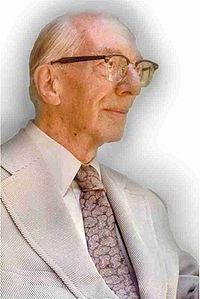

A political philosopher, Eric Voegelin (1901-1985) has the reputation of being a philosopher of history. His magnum opus Order and History is regarded as comprising an early phase (the first three volumes) and a later phase (the last two volumes).

Eric Hermann Wilhelm Voegelin was born in Cologne and subsequently educated at Vienna, where he gained a doctorate in political science. His professorial role at the University of Vienna was terminated in 1938, because he resisted association with the Nazi cause of Adolf Hitler. He had written two books criticising the Nazi “master race” theory. Voegelin narrowly escaped the Gestapo, who were very disapproving of dissidents.

Fleeing with his wife to America, he continued an academic role, becoming an American citizen in 1944. He became a professor of political science at Louisiana State University, which continues to honour his memory (see also The Voegelin Enigma).

During the 1940s, his outlook moved at a tangent to the history of political ideas, in which he had written extensively. His new orientation involved a form of existentialism, in reaction to Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) and the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl (1859-1938). Voegelin’s existentialism was very unusual, exhibiting a Platonist complexion, further associated with a Christian background. Hence my description in terms of an existential Christian Platonism. However, he did mute certain Christianising tendencies in his later years.

Voegelin is also unusual for his linguistic affinities. He learned both Greek and Hebrew, acquisitions by no means common amongst philosophers. He was thus able to read Plato in the original, while studying the Old Testament in depth.

By the 1950s, he had developed a theme of rediscovering the philosophical quest via an experiential mode, meaning that philosophy was not just a format of ideas but an existential process of experience. He also railed against the influence of positivism and scientism. Voegelin became noted as a critic of modernity. These tendencies became controversial. His enduring opposition to Fascism was accompanied by a strong reaction to both G. W. F. Hegel and Karl Marx, not to mention various other modern exponents. Voegelin classified all these figures under the generalising term of Gnosticism. His idiom is considered by some analysts to comprise an extreme usage of that word, perhaps reflecting to some extent his Christian upbringing.

The first volume of Order and History afforded a coverage of ancient Israel. This version of Biblical events drew upon scholarly sources available by the 1950s. Many of those are now outdated. Since that time, archaeology has uncovered numerous details formerly unknown. This development led to a basic rift between differing approaches to the Old Testament. What emerges today is that the Hebrew Bible is basically a late post-exilic composition, including some earlier components much debated.

Voegelin argued that the ancient Israelites did not progress to the “noetic differentiation” in process amongst the Greeks. The presumedly “compact” nature of the Israelite experience of spiritual life was here viewed as preventing the development of philosophy, which for Voegelin, involved “the explicit experience of divine presence as an ordering force within the individual psyche of the philosopher” (quote from Christian neoexistentialist). However, intrinsic existence would always remain a mystery, he believed. In this context he stressed resort to the language of myth.

Some attention was given by Voegelin to the Israelite prophets. The books attributed to prophetic entities like Amos, Isaiah, and Jeremiah are the focus of detailed scholarship. How far such texts represent the entities named is an elusive matter. They were cast in the form of a post-exilic Jewish understanding, in the early centuries BCE, though earlier themes and content may intervene.

In volume two of Order and History, the author surveys trends in early Greek literature and philosophy; he analyses features of the polis or city-state. Voegelin continues this treatment in volume three, devoted to Plato and Aristotle. A fairly detailed version of Greek events does emerge, quite distinctive in certain respects, with room for disagreement on some points. See Voegelin and Plato.

From Homer to Aristotle, Voegelin pursued his favoured themes attendant upon the key feature of order in the soul or psyche. This leitmotif was purportedly evolved by philosophers in opposition to the political activities of the polis. The philosophical process could not be institutionalised like the rival, being dependent upon individual contributions and achievements. In this way, Voegelin counters conventional conceptions of philosophy as an “intellectual” activity concerned with mere ideas and arguments.

He clearly preferred Plato to Aristotle, while attempting to give the Stagirite a due credit. Voegelin celebrated Plato’s Dialogues and the attention given to philosophical mythic formulation. He analyses the Timaeus, the Republic, and the Laws, all of these works demanding a more than casual attention from the modern reader. The contrasting, or complementary, bios theoretikos of Aristotle also gains profile.

So far Voegelin had inserted a number of Christianising comments, leading some readers to expect a culminating coverage of Christianity in terms of the desired order. Yet in volume four, published in 1974, the author frustrated those assumptions. He admitted to encountering a problem in his conception of history. Voegelin now viewed a linear time scheme as an error. Proliferating researches were revealing the complexity of world history. Even New Testament scholarship was adopting new criteria. Voegelin learned with dismay that the Gospel of John was now considered to exhibit Gnostic tendencies.

The rigidity attaching to orthodox Christian ideas of Gnosticism was substantial until the late twentieth century. Discovered in 1945, the Nag Hammadi texts challenged some entrenched notions, giving scholars a far more accurate idea of early Gnostic beliefs, which circulated amongst different groupings. Translations did not become readily accessible until the 1970s, when Voegelin had already formulated his basic outlook. The Nag Hammadi Library in English (Leiden, 1977) made available the “Coptic Gnostic library.”

The tendency of Voegelin, to use Gnosticism as a blanket term for modern ideological trends, is discrepant to some contemporary readers. Both Hegel and Marx were designated as Gnostics by the existential Christian Platonist. Hegel was a Protestant Christian; the iconoclastic atheist Karl Marx does not equate with Gnostics of the Roman era. Hegel’s “science of logic” affords a contrast to the “neo-Thomist” deliberations of Voegelin. However, both of these exponents can be considered philosophers of history. See Voegelin and Gnosticism.

Voegelin’s “non-linear” tangent touched upon Pauline Christianity, while ranging into differing eras of world religion. He found some Eastern religions defective in comparison to (Greek) philosophy. He tended to favour some religious phraseology of Thomas Aquinas, the neo-Aristotelian with a strong Dominican profile. In contrast, Joachim of Fiore and Siger of Brabant were two of the many stigmatised “Gnostics” in the neo-existential panorama.

The relatively brief volume five (curtailed in size by the author’s death) was subtitled In Search of Order. Hegel is again one of the ingredients, apparently regarded by Voegelin as the major modern predecessor and rival.

Bibliography:

Trepanier, Lee, and Steven F. McGuire, eds., Eric Voegelin and the Continental Tradition (University of Missouri Press, 2011).

Voegelin, Eric, Order and History (5 vols, Louisiana State University, 1956-87).

———The New Science of Politics (University of Chicago Press, 1952; repr. 1987).

———Anamnesis: On the Theory of History and Politics (Collected Works of Eric Voegelin Vol. 6), ed. David Walsh (University of Missouri Press, 2002).

Webb, Eugene, Eric Voegelin: Philosopher of History (University of Washington Press, 1981).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd (2011, slightly modified 2020)

ENTRY no. 40

Copyright © 2020 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.