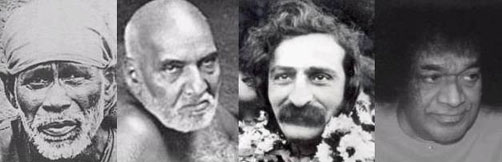

Shirdi Sai Baba, Upasani Maharaj, Meher Baba, Sathya Sai Baba

A phrase that has become fairly well known is not in general duly analysed. This phrase, namely the “Sai Baba movement,” has caused much confusion and misconception. Ignorance of the matter is so pronounced that a Wikipedia editor attributed the origin of this phrase to myself. In reality, I merely wrote a book whose title included the phrase under discussion, over thirty years after the phrase first appeared in academic literature.

The category “Sai Baba movement” was innovated in the early 1970s by Charles White, an American scholar who wrote an article on this subject that can be strongly faulted. White associated two Indian celebrities who had the same name; the resulting confusion became accepted by some academics as a legitimate argument for viewing various events in terms of a “Sai Baba movement.”

Twenty years later, the misconception developed to the stage where a leading American university press published a book with a rather explicit statement on the paperback cover. The State University of New York Press declared that “a vast and diversified religious movement originating from Sai Baba of Shirdi, is often referred to as ‘the Sai Baba movement.’ ” This statement supported the contents of a book by Dr. Antonio Rigopoulos about Sai Baba of Shirdi (d.1918).

Rigopoulos was clearly in support of the “Sai Baba movement” formulation devised by White. Both White and Rigopoulos were partisans of Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011). They evidently wished to support that guru’s lavish claim to be the reincarnation of Shirdi Sai.

Sathya Sai Baba, of Puttaparthi, was believed to be an avatar by his followers. He created an elaborate avataric hagiology that included Shirdi Sai Baba. Sathya Sai categorically claimed to be the reincarnation of Shirdi Sai. However, the claim was elsewhere strongly resisted by followers of Shirdi Sai. The claim was regarded, by the Shirdi contingent, as an opportunist fiction.

One of the more well known instances of disagreement occurred when, in 2006, devotees of Shirdi Sai filed an objection in the court at Rahata (near Shirdi). They requested a permanent injunction on claims made by devotees of Sathya Sai that the latter is a reincarnation. Also at issue here was Sathya Sai lore about the birth of Shirdi Sai, including the purported identity of his mother (Mumbai Mirror, 11/01/2006, “Case filed in India”).

I provided biographical and other materials in the book Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (2005). This volume is annotated and indexed. I covered the three major figures in Maharashtra who were incorporated by Rigopoulos into the “Sai Baba movement” scenario. I am referring to Shirdi Sai Baba, Upasani Maharaj (d.1941), and Meher Baba (d.1969).

On the basis of the actual data available, these three entities do not emerge as part of a conglomerate movement. Rather, each of these mystics created a distinct movement or following in their own name. However, this trio were strongly interconnected, in that they met each other. Moreover, Upasani was the disciple of Shirdi Sai, and Meher Baba was the disciple of Upasani. In contrast, Sathya Sai did not meet any of these three saints, and lived in a different region of India.

Sathya Sai Baba, of Andhra, is viewed by some partisans as the culmination of events in Maharashtra. Critics affirm that this theme encounters a difficulty in sustaining credence. The partisan idea is supported by belief in the reincarnation claim of Sathya Sai, not by any facts of continuum. What we are actually confronted with here is the spectacle of four separate movements, the one based in Andhra having no effective resemblance to the three movements originating in Maharashtra.

When the biographical details are investigated, there may be strong reason to doubt the legitimacy of a reincarnation claim. The ascetic lifestyle of Shirdi Sai features pronounced differences to that of his namesake. Sathya Sai adopted the name of the Shirdi saint in the early 1940s, gaining much popularity as a consequence.

My book included three appendices reporting the disillusionment of Western ex-devotees of Sathya Sai Baba. I also made reference to the leading Indian critic of Sathya Sai, namely Basava Premanand (d.2009), of Indian Rationalist fame (who composed a lengthy book on the notorious bedroom murders at Puttaparthi ashram in 1993).

In 2006, Investigating the Sai Baba Movement was favourably cited in a Wikipedia article about an academic ex-devotee of Sathya Sai. This was Robert Priddy, whose report I had included in my book. The online citation was strongly resisted by a Wikipedia editor, who transpired to be an American apologist for the Sathya Sai movement. SSS108 (alias Gerald Joe Moreno) pressed for deletion of the Priddy article, and also produced a Wikipedia User page dismissing the validity of all my books. It became obvious that Moreno had not read these books, instead reacting from a sectarian stance of strong antipathy towards ex-devotees and anyone who favourably mentioned them. The Moreno internet campaign of defamation lasted until 2010.

Research into the “movement,” or rather movements (in the plural), is not so easily to be eliminated by ideological conveniences preferred by “crowdsourcing” (to borrow a description of Wikipedia process favoured by academic affiliates of the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy).

In another camp, some Western devotees of Meher Baba, acting as editors on Wikipedia, refused to acknowledge the relevance of Investigating the Sai Baba Movement. They likewise had evidently not read the book; they only knew of the title. One of them mistakenly insinuated that I had coined the phrase “Sai Baba movement.” Until such denominational antipathies and errors of judgment are improved, Wikipedia and other internet media are likely to remain afflicted by misinformation. The suppression of relevant reports, on whatsoever pretext, is no effective substitute for due evaluation.

Some partisans of Sathya Sai Baba refer to the “Sathya Sai movement.” This is quite a different idiom, and equivalent to “Meher Baba movement” or “Shirdi Sai movement.” Identification of these trends, in terms of separate movements, is surely preferable to the umbrella phrase “Sai Baba movement,” which has logical difficulties of exegesis. See further Sai Baba Movement at Issue.

Misconceptions are evident, even in some academic books, about the actions of Shirdi Sai. For instance:

Many were suspicious of his claims… but he [Sathya Sai] reportedly substantiated his claims with miraculous acts. For example, Sathya Sai Baba, as he had come to be known, regularly materialised healing vibhuti, sacred ash which devotees imbibe and/or apply to their foreheads. These materialisations established Sathya Sai Baba’s connection to Shirdi Sai Baba, who had also materialised vibhuti for his followers. (Srinivas 2010:9, and citing Srinivas 2008)

Such statements attest a pronounced confusion about the supposed similarity between Shirdi Sai and Sathya Sai. In reality, the Shirdi saint did not materialise sacred ash, nor did he claim to do so. Instead, Shirdi Sai merely took ash from his dhuni fire, located inside the mosque where he lived (Shepherd 2015:398-399 note 730). In contrast, Sathya Sai claimed to miraculously materialise ash from thin air. Indian critics like Basava Premanand have described (and demonstrated) the action of Sathya Sai in terms of sleight of hand, a perspective differing radically from the deceptive version.

One interpretation has emphasised the term avatar in terms of an advantage for the Sathya Sai movement. This is not agreed upon by all parties. An academic review states:

Whereas Shirdi Sai Baba mixed elements of a Sufi faqir, Hindu guru, and devotional sant, Sathya Sai Baba consistently adopts the term avatar, a divine being who descends from above at a time when truth and righteousness are threatened. [Smriti] Srinivas proceeds to argue that his identification as an avatar increases Sathya Sai Baba’s scope of travel and creates a greater capacity to reach devotees, in contrast with an identification as a faqir, guru, or sant. (Loar 2009:1)

Some discrepancies are discernible. The conception of Shirdi Sai as a devotional sant is misleading. The Shirdi saint has been depicted as both a Sufi faqir and a Hindu guru. A substantial number of portrayals limit the attention to detail that is possible in this instance.

The claim of Sathya Sai to avataric status does not establish any priority in communication over Shirdi Sai in relation to devotee followings. The guru of Puttaparthi contributed a lavish puranic mythology of Shirdi Sai, this development assisting a general tendency to marginalise historical dimensions of the latter. The overall consequence of this preference was to obscure contextual data relating to the Shirdi saint, who furthered an eclectic approach to Sufism and Hinduism.

Bibliography:

Loar, Jonathan, review of Smriti Srinivas, In the Presence of Sai Baba, in Practical Matters: A Journal of Religious Practices and Practical Theology (2009, Issue 2, 1-3).

Premanand, Basava, Murders in Sai Baba’s Bedroom (Podanur, Tamil Nadu: B. Premanand, n.d., but 2001).

Rigopoulos, Antonio, The Life and Teachings of Sai Baba of Shirdi (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

——Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2015).

Srinivas, Smriti, In the Presence of Sai Baba: Body, City, and Memory in a Global Religious Movement (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

Srinivas, Tulasi, Winged Faith: Rethinking Globalization and Religious Pluralism Through the Sathya Sai Movement (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

Warren, Marianne, Unravelling the Enigma: Shirdi Sai Baba in the Light of Sufism (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999; new edn, 2004).

White, Charles S. J., “The Sai Baba Movement: Approaches to the Study of Indian Saints,” Journal of Asian Studies (1972) 31:863-878.

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 68

Copyright © 2016 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.