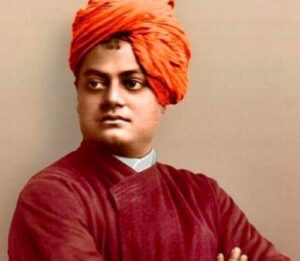

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902) was anti-caste in many of his recorded emphases. He was an unusual mystic, of the more daring and radical kind, in terms of social extension. Yet he identified with the traditional philosophy of Advaita Vedanta, strongly associated with Shankara (c.800 CE), a legendary exponent whose extant and attributed treatises are a subject of complex scholarly appraisal.

Vivekananda, alias Narendra Nath Datta, was born in Calcutta, where he attended college. He studied European history and philosophy, gaining a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1884. Narendra came from a low class background, being a kayastha by birth. That sub-caste gained an increased status in Bengali society under British rule, often working as clerks and secretaries. His father was a prosperous attorney at the Calcutta high court. A strong influence upon Narendra was the Brahmo Samaj, a reforming movement advocating belief in a formless God; the Brahmos were in opposition to popular Hinduism.

In 1881, Narendra encountered Ramakishna of Dakshineswar (1836-1886), a brahman saint who lived in a Kali temple near Calcutta. Ramakrishna was not typical of the priestly caste; he would not touch money and spoke in very simple language, as distinct from the formal didactic of the pundits. The tendency of Ramakrishna was eclectic with regard to Hinduism, including reference to Advaita Vedanta.

Narendra at first rejected Advaita, deeming this an extremist philosophy. Ramakrishna’s esteem for the goddess Kali was also repugnant to reformist tastes. However, the consequence was that Narendra changed orientation completely, becoming a full-fledged disciple of the mystic.

Vivekananda as wandering sannyasin in 1892

The young disciples of Ramakrishna opted for a monastic existence at his death, living in a dilapidated house at Baranagore. A number of them took formal vows; Narendra assumed the name of Swami Vivekananda. In 1888, he left Baranagore to live as a wandering monk (sannyasin). For several years he travelled throughout India, frequently travelling on foot; he resorted to the railway when given tickets by wellwishers. He encountered priestly pundits and maharajas; he also saw at firsthand the widespread poverty and suffering of the masses, which evidently weighed upon him deeply.

At the end of 1892, he arrived at Cape Comorin (the southern tip of India). There he gained a much reported insight: the situation of so many wandering renunciates, teaching religion, was seriously discrepant. Instead the objective should be one of raising the masses from ignorance and hunger.

In 1893, Vivekananda visited America as an outspoken teacher of Vedanta and Yoga. He first lectured at the Chicago Parliament of Religions, gaining both admirers and critics, the latter including missionaries to India. For over three years he stayed in the West, lecturing in America and England; he suffered poor health as a consequence of the strain. He declined two offers of an academic chair in Eastern philosophy at Harvard and Columbia Universities, explaining that he could not accept such a career role in his vocation as a wandering monk.

In early 1897, Vivekananda arrived back in India, being welcomed as a national hero on account of his recent fame. He travelled nationwide from Colombo to Calcutta and Almora, frequently giving lectures that included exhortations to an upliftment of the masses and the elimination of caste stigmas. He also favoured the study of Western science in addition to Vedanta. The implications of a national reorientation were taken seriously in some directions; later political figures like Mahatma Gandhi and Radhakrishnan acknowledged Swami Vivekananda as an inspiration. Independence from British rule was one repercussion. However, Vivekananda did not mount a nationalist campaign. Instead, his immediate opponent was the conservative priestly caste. Subsequent nationalists, who favoured violent agitation against the British, were not compatible with the monastic ahimsa of Vivekananda.

This monk detested what he called the “kitchen religion” of the brahman caste, a belief system entailing a taboo on food being defiled by the shadow of any untouchable. “Kick out the priests who are always against progress,” said Vivekananda. A British archaeologist, Frank Allchin (1923-2010), commented of this Hindu radical: “The modern student of sociology may well be surprised at the depth and objectivity of his observations” (quotes from Allchin 1968:89ff,102). Dr. Bhimrao R. Ambedkar, the Dalit leader, is known for asserting that Vivekananda was the greatest man in India during recent centuries.

At Calcutta in 1897, Vivekananda founded at Belur the Ramakrishna Math (monastery). This was accompanied by the Ramakrishna Mission, an extension in social service. Some Christian critics say that the Mission was inspired by Christian models. The new Hindu monastic organisation later gained a centre in Madras.

During 1899-1900, Vivekananda again visited America and Europe, creating Vedanta centres in San Francisco and New York. He also attended the Paris Congress of Religions (1900). Because of his failing health, he was unable to meet an invitation to the subsequent Congress of Religions in Japan. Vivekananda died peacefully at the Belur monastery, while lying down after meditating.

An Indian historian (Amiya Prosad Sen) observes that Vivekananda “was often strongly anti-Brahmin, if not also anti-Brahmanical, and held saints and sadhus no less responsible for the continuing oppression of the masses. Reformers, in his view, never really touched the pulse of India…. Vivekananda’s panacea for India’s several ills was mass education: training in useful sciences and crafts, manual skills, and manufacture” (Sen 2006:33-4).

A generally obscured matter is that Vivekananda drew from both the Sankhya and Vedanta systems of philosophy. He emphasised features of Sankhya psychology, while admitting the indebtedness of Vedanta to Sankhya. Substantial doctrinal differences existed between those two traditions (ibid:40).

A Western scholar has commented:

Although the Ramakrishna movement is not considered an orthodox sampradaya [religious tradition] by the more conservative Hindus, it has nevertheless captured the imagination of a great many modern and progressive Hindus and is held to be a non-sectarian and universal expression of a new, reformed Hinduism. (Klostermaier 1989:45)

The Ramakrishna Order now claims over 200 branch centres, mainly in India. There is an online partisan biography of Vivekananda by Swami Nikhilananda. A critical version states that some biographies “contain a lot of misinformation, tendentious statements, apologetics and plain lies” (Chattopadhyaya 1999:vii). Certain “corrective” treatments are clearly biased against the celibate monastic lifestyle, a factor not necessarily conducive to accuracy.

There is a well known instance of an academic who encountered homosexuals in a Christian monastery, afterwards projecting his “homoerotic” obsession upon Ramakrishna, while implying that Vivekananda was misled. This eccentric exegesis was supported by a Christian theologian, whose biases likewise prove nothing about Indian mystics.

Bibliography

Allchin, Frank Raymond, “The Social Thought of Swami Vivekananda,” in S. Ghanananda and G. Parrinder, eds., Swami Vivekananda in East and West (London: Ramakrishna Vivekananda Centre, 1968).

Burke, Marie Louise, Swami Vivekananda in the West: New Discoveries (2 vols, 1957; 6 vols, Advaita Ashrama, 1983-96).

Chattopadhyaya, Rajagopal, Swami Vivekananda in India: A Corrective Biography (Banarsidass, 1999).

Dhar, Sailendra N. A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda (2 vols, 1975-6; second edn, 3 vols, Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 2012).

Klostermaier, Klaus K., A Survey of Hinduism (State University of New York Press, 1989).

Sen, Amiya P., Swami Vivekananda (2000; second edn, Oxford University Press, 2013).

——–Social and Religious Reform: The Hindus of British India (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Sen, Amiya P., ed., The Indispensable Vivekananda: An Anthology for our Times (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2006).

Sil, Narasingha P., Swami Vivekananda: A Reassessment (Susquehanna University Press, 1997).

Vivekananda, Swami, Complete Works (nine vols, Advaita Ashrama, 2001).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

August 6th, 2010 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 28

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.