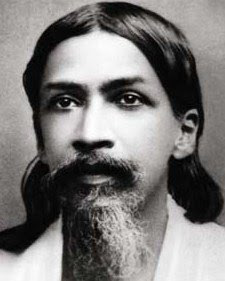

Aurobindo Ghose

An influential guru figure was Aurobindo Ghose (1872-1950). One complaint is that many books on Aurobindo tend strongly to hagiography. Some assessors say that the best biographical portrayal is by Peter Heehs, meaning The Lives of Sri Aurobindo. The author comments: “From 1921 on most descriptions of Aurobindo read as though they were taken out of the puranas or the mythological texts” (Heehs 2008:330). Some devotees blocked publication in India of the Heehs book, which received favourable reviews. A related feature is informative:

Heehs is gently sceptical of the claim that Aurobindo possessed supernatural powers. “To accept Sri Aurobindo as an avatar is necessarily a matter of faith,” he writes, adding that “matters of faith quickly become matters of dogma.” This understated, unexceptionable statement drove the dogmatic followers of Aurobindo bananas. Some devotees filed a case in the Orissa High Court, restraining the Indian publisher from circulating the book in India.” (Ramachandra Guha, Ban the Ban, 2011)

Aurobindo was a Bengali, born at Calcutta (Kolkata). The pater, a surgeon, wanted his children to have a British education. The young Aurobindo (Aravinda) was accordingly despatched, with two brothers, to Manchester, where he was tutored by an Anglican clergyman. In addition to English literature, he also learned Greek and Latin. He entered King’s College, Cambridge, following paternal wishes for a career in the Indian Civil Service. As events transpired, Aurobindo did not take employment under the British.

When he returned to India in 1893, he joined the bureaucracy of the Gaekwad of Baroda, a city of Western India where he resided for thirteen years. Many details of that phase in his life are on record. His patron was the liberal Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III, who favoured reformist activities such as prohibition of child marriage. Aurobindo penned speeches for the Gaekwad, becoming a professor of English at Baroda State College. He made a private study of Bengali literature, and learned Sanskrit without assistance. In 1901, Aurobindo married the daughter of an Indian government official. By 1903, he was evidently a nationalist revolutionary.

In 1906 he moved to Calcutta, where he joined the Indian National Congress. He criticised that Congress for a moderate policy on national education. Aurobindo became one of the extremists. The major issue was now the British partition of Bengal in 1905, effectively separating Muslims from Hindus. This “divide and rule” strategy of Lord Curzon (the Viceroy) was very unpopular with Hindus (eventually the government plan was abandoned). The Bengal Presidency was the largest province in British India, with a population of over 80 million.

Bengal was depicted by Hindus as the Goddess victimised by the British. “Militant political leaders primarily drew upon Shakta symbolism, especially the imagery of the Hindu cult of Kali worship, and they adopted philosophical justifications of nationalism which were based on modernist, neo-Hindu interpretation of Shankara’s Vedanta philosophy” (Barbara Southard, The Political Stategy of Aurobindo Ghosh, 1980).

Aurobindo became a major contributor to the nationalist newspaper Bande Mataram. In 1907, the British government moved to prosecute this bulletin, which they regarded as a goad to violence and lawlessness. That year, Aurobindo was arrested by the police on a charge of sedition. He was subsequently acquitted because of failure to establish his editorship of the insurgent newspaper. By this time, Aurobindo was a major figure in the increasingly militant independence movement, a body prepared to justify murders undertaken by members of the kshatriya class.

The American historian Peter Heehs has revealed how the Indian freedom struggle, of this early phase, had both violent and non-violent aspects. Passive resistance was only part of the story. There was a tendency to terrorism in the 1900-10 decade of the Bengali resistance. Heehs penetrates the hagiography attaching to Aurobindo. At this early period, the future Yogi was a member of the extremist Jugantar party, based in Calcutta, in which his brother strongly figured. These revolutionaries stockpiled weapons and explosives. Moroever, they secretly manufactured bombs in a garden house at Manicktola, located in a Calcutta suburb. Aurobindo was evidently in agreement with violent tactics, though he did not apparently become directly involved in that extension. He is described by some commentators as a strategist or organiser.

During 1907-8, Aurobindo travelled to Poona (Pune), Bombay, and Baroda. As an emissary of the nationalist cause, he was seeking further support. In May 1908 he was again arrested, this time as a suspect in the Manicktola Conspiracy, also known as Alipore Bomb Case. His younger brother, Barindra Kumar Ghose (1880-1959), was Jugantar leader of young Bengali revolutionaries at Calcutta. This group resorted to a bomb attack in April 1908. Their plan was to bomb the horse carriage of a British magistrate, whom they detested for administering harsh sentences. The punitive action miscarried. The insurgents bombed the wrong carriage, killing two innocent British women.

About thirty men were arrested, including Aurobindo. The Manicktola property of the extremists was raided by police, who discovered “inflammatory literature, loads of explosives, arms and ammunition, along with detailed written instructions on the techniques of manufacturing higher explosives” (quotation from Alipore Bomb Case, 2009).

Barindra Ghose admitted to responsibility in the lengthy trial that followed. The verdict of the court initially entailed death sentences. Deportation to the Andaman Islands was the final sentence for a number of the accused. Aurobindo and over fifteen others were acquitted in 1909. Jugantar militants murdered two opponents who had worked against them.

Meanwhile, Aurobindo was detained in solitary confinement for one year at Alipore jail; there he studied the Bhagavad-Gita. He subsequently reported a number of spiritual experiences during his incarceration. After being freed, he commenced two new weekly journals, promoting his radical ideas on national education. His anti-British tendency caused the Viceroy Lord Minto some misgivings. In private correspondence dating to 1910, Lord Minto described Aurobindo as “the most dangerous man we now have to reckon with.”

That same year, Aurobindo retired from the political arena. He took refuge in the French colony of Pondicherry (in Tamil Nadu), after receiving news that the Indian police were looking for him again. Now he opened a new chapter in his career, devoting himself to Yoga (one of his former subsidiary interests). Some critics have viewed this phase as an escape route from political problems. However, Aurobindo was evidently quite sincere in the subsequent and extensive cycle of mystical writings, appearing in his new monthly journal Arya from 1914 onwards. In that mode, his major works first emerged in a serialised format, notably including The Life Divine and The Synthesis of Yoga.

The former political agitator was now the exponent of an avant garde Hinduism, “developing a philosophical system inspired by Vedanta, but integrating elements from Yoga, Tantra and the theory of evolution” (Flood 1996:270).

Afterwards, in 1926 was founded the Aurobindo Ashram, with a core of 24 disciples. That same year, Aurobindo withdrew into seclusion, appointing a woman as the ashram leader. Mirra Richard, also called Mirra Alfassa (1878-1973), became known as “the Mother.” She was a Parisian of Turkish and Egyptian parentage. Aurobindo acknowledged her as his major disciple.

During the 1930s, a correspondence with disciples formed the main literary output of Aurobindo, eventually becoming the Letters on Yoga (3 vols). He also worked on a lengthy poem entitled Savitri. Aurobindo did not revert to political agitation. During the Second World War, he supported the Allied cause against Hitler, whom he described as an oppressor.

His major work is The Life Divine, first published in 1914-19 in serial form, later revised and enlarged for publication in book format (2 vols, 1939-40). The lengthy contents expound his version of spiritual evolution. An accompanying work, The Synthesis of Yoga, formulates what is known as Integral Yoga, which Aurobindo regarded as a unique innovation. The declared objective is transformation of the individual, including physical, psychic, and mental dimensions. The acquisition of an “inner Yogic consciousness” has the objective of “supramentalisation.” This version of Yoga is often described as uniting the dispositions of bhakti, jnana, and karma yoga as mentioned in the Bhagavad-Gita, a popular Vedantic text of Hinduism.

Aurobindo opposed aspects of Advaita Vedanta, including mayavada, the doctrine that the world is an illusion. He also diverged from the Vedantic belief that an ascetic life of withdrawal is the means to liberation. Aurobindo improvised the theme of Supermind, which he also described as gnosis. He has been credited with introducing the concept of evolution into Vedantic thought. However, his version of evolution was not that of Darwinism, which Aurobindo regarded as a materialist limitation.

A disputed feature of his doctrine is that of a new supramental or gnostic human species envisaged for the future. This theme became influential in the subsequent American “new age” variation associated with the Esalen Institute of California (Aurobindo and Esalen). Some think that Aurobindo was more realistic in referring to the “intermediate zone,” meaning a danger area of deceptive spirituality, located between mundane consciousness and genuine spiritual achievement. One surely sees far more of this drawback than anything “gnostic” in the pretentious new age.

Specialist scholarship, in Vedic texts, has disagreed with Aurobindo’s theme of an esoteric meaning in the ancient RigVeda. Via such works as The Secret of the Veda and Hymns to the Mystic Fire, Aurobindo asserted that the Rig was composed in a symbolic language. The outer meaning is here conceived as relating to religious rituals, while the inner meaning pertains to a spiritual knowledge. In contrast, Professor Jan Gonda viewed this as an erroneous interpretation. For Aurobindo, the Vedic sacrifices are all symbolic, the Rig ritualism being regarded as an “infallible authority for spiritual knowledge.” The critical Indologist did not deny an intuitive dimension to the poetry of the Rig rishis (Gonda 1975:53-4). Gonda was not the only sceptical scholar. The RigVeda context is still emerging (Jamison and Brereton, 2014).

After Aurobindo’s death, the town of Auroville was founded near Pondicherry in 1968. The ideal was an international habitat transcending creed and politics. Auroville gained nearly 3,000 inhabitants from many countries, mainly Indians, French, and Germans.

Bibliography

Aurobindo, The Life Divine (first edn 1939-40; seventh edn, Pondicherry, 2006).

——–The Synthesis of Yoga (Pondicherry, 1996).

——–Secret of the Veda (Pondicherry, 1995).

Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo (30 vols, Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1972).

Flood, Gavin, An Introduction to Hinduism (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Gonda, Jan, Vedic Literature (Wiesbaden: Harrasowitz, 1975).

Heehs, Peter, The Bomb in Bengal: The Rise of Revolutionary Terrorism in India, 1900-1910 (Oxford University Press, 1993; second edn, 2004).

——–The Lives of Sri Aurobindo (Columbia University Press, 2008).

Jamison, Stephanie W., and Joel P. Brereton, trans., The Rigveda (3 vols, Oxford University Press, 2014).

Purani, Ambulai B., The Life of Sri Aurobindo (1978; fourth edn, Pondicherry: Aurobindo International Centre for Education, 1987).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

August 2010 (modified 2018, 2021)

ENTRY no. 30

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.