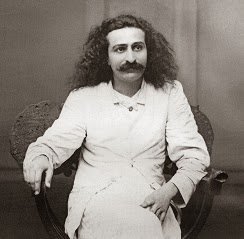

Meher Baba, 1930; Paul Brunton in India

Paul Brunton wrote the book called A Search in Secret India (1934). This became a bestseller. Reprints were eventually adorned with the credential of Dr. Paul Brunton. The British author became regarded by many as an authority on Indian religion.

I have talked with people who are under the impression that Secret India is a reliable document. Any suggestion to the contrary can be met with incredulity and outright denial.

In my early years, I met two persons of a literary ability who were able to analyse Secret India, though in different ways. The first was a teacher of English (at Cambridge) who found Brunton’s style deficient, a style which he associated with low grade journalism as distinct from scholarship. Indeed, he laughed at some phraseology he found. This academic was nevertheless inclined to believe a popular view that the contents were accurate, because of the doctoral status claimed.

The other analyst had actually met Paul Brunton (1898-1981). This critic denied the validity of Secret India in relation to Meher Baba. Charles Purdom (d.1965) was a literary man who had daringly ventured into biography of Meher Baba, despite the relatively marginal Western interest in his day. Purdom wrote that Brunton, “then known as Raphael Hirsch, came to see me in London some time after his visit” to the ashrams of Meher Baba. On that occasion, Brunton “said he had no doubt [Meher] Baba was false, as he, Raphael Hirsch, had asked him to perform a miracle but Baba could not” (Purdom 1964:128).

In brief, Purdom had deduced that restraint from performance of a “miracle” is no proof of falsity. On the contrary, he believed that Brunton’s attitude was confused and misleading. Purdom was also very sceptical of the doctoral status advertised by Brunton’s publisher. The background of the Ph.D. credential proved exasperatingly obscure.

Purdom was a follower of Meher Baba, very closely acquainted with how that entity lived and taught. He early wrote a biography, published in 1937, that was overshadowed by Brunton’s commercial “Secret.” Purdom’s book is today cited by commentators who can discern that he was attempting an objective report of his subject. The sub-title is The Life of Shri Meher Baba, revealing the idiom in which the subject was then known.

Many years ago, I researched the Brunton problem, discovering materials that Brunton had omitted from his book. The missing data, and loss of context, invalidate Brunton’s report of Meher Baba to a very substantial extent.

Secret India is noted for a rejection of Meher Baba (1894-1969) in favour of Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950). Both of these figures are now famous twentieth century mystics, associated with rather different teachings. There is no indication that Brunton actually understood the teaching of Meher Baba; however, he did assimilate Vedantic emphases of Ramana. Indeed, to such an extent that he eventually became notorious as a plagiarist, with the consequence that he was banned from the ashram of the Advaita sage in 1939.

Paul Brunton can scarcely be gauged without reference to his background in Western occultism. During the 1920s, he was part of the avant garde “bohemian” scene in London, strongly influenced by Theosophy and numerous “esoteric” trends, some of these so dubious that even the enthusiasts rejected them. Yoga was a fashion to which Brunton became very partial. The subject of Yogic siddhis (powers) excited Western occultists. Brunton believed that he himself early gained occult powers and abilities. According to his own report, he was able to miraculously extinguish lighting at the lecture hall of an opponent.

Brunton’s business as a “freelance journalist” failed in 1929. The following year, he travelled to India as an enthusiastic follower of Shri Meher Baba. He visited two ashrams of the latter, and in between, he undertook a tour of various places at the instruction of Meher Baba. At Madras he ventured a public declaration of his purportedly “telepathic” experiences concerning Meher Baba. In a subsequent letter sent from Calcutta to his inspirer, Brunton mentioned that he was looking forward to “receiving spiritual enlightenment at your hands.”

These are some of the realistic details. A major problem for unwary readers is that Brunton, in his bestselling book Secret India, omits crucial reference to the context. Presented instead is a deceptive narrative in which Brunton was a sceptical enquirer; he demeans the two non-Hindu ashrams he visited, writing as if he conducted the tour of his own volition, with the objective of visiting Yogis possessing hermetic knowledge. Relevant documentation is scrupulously missing. Brunton’s travelogue is undated, assisting the impression of a lengthy search in “secret India” that actually lasted only a few months. Brunton also supplied a very misleading description of Meher Baba’s facial appearance.

As a consequence of these varied flaws, the book A Search in Secret India cannot be taken seriously as an accurate report, only as a testimony to what can go wrong in accounts deriving from pique and attendant emotions of a suspect nature.

I contributed a book including a confrontation with the Brunton problem. Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (1988) was the first published account to divulge what Brunton omitted, and to reconstruct what really happened. The responses were mixed. Some followers of Brunton were prepared to concede that he had made a mistake in his assessment. However, they were unable to accept the overall implications, instead affirming that Brunton’s lengthy Notebooks of a later period were a redeeming feature.

Some American devotees of Meher Baba unofficially banned Iranian Liberal because of some (relatively mild) criticisms of their own spokesmen (I am not a devotee of Meher Baba). They consigned to oblivion the only published account vindicating the reputation of their own figurehead in the face of “Secret India” opportunism.

Very briefly, Paul Brunton effectively associated Meher Baba with Yoga, together with the desired powers and experiences that he was so fixated upon. Meher Baba was not in fact a Hindu and never taught Yoga; he was an Irani Zoroastrian with a teaching sometimes described as eclectic. Meher Baba was opposed to any occultist pursuit of siddhis. In his early years he wore his hair long; this trait doubtless assisted certain “hermetic Yogi” impressions in Brunton’s mind. The visitor wanted “spiritual” experiences; he triumphantly aired his telepathic prowess. Telepathy is a Yogic power, as Brunton knew very well. For reasons that are not too difficult to fathom, the Irani mystic disconcerted the expectations.

The frustrated British occultist chose to depict his former host and inspirer as an obsessive messiah figure who promised him powers, but could not supply them. The Irani is made to look so ridiculous that readers are led to believe he was a hopeless fraud. That version of events made Paul Brunton, in commercial estimation, the great British critic of Secret India.

The popular writer produced further books such as A Search in Secret Egypt and The Secret Path. These confirmed to critics that Western occultism is not basically secretive, whatever the mysteries proclaimed; the secrets exist to be disclosed or advertised, and perhaps even exploited. In this trend, the supposed adept of Vedanta eventually wrote The Hidden Teaching beyond Yoga (1941), a book including controversial criticisms of Ramana Maharshi, from whose ashram he had been banned.

Followers of Brunton have celebrated his association, in the late 1930s, with the milieu of Krishnaraja Wadiyar (d.1940), the Maharaja of Mysore. At the court of this royal celebrity, Brunton gained servants and material assistance. His new counter-ideal to Ramana was apparently the Maharaja, whose family derived support from British colonial power. The Maharaja favoured industry and technology. A tutor of the Maharaja was Subrahmanya Iyer, a neo-Vedantin brahman associated with modernist ideas and Western philosophy. In the company of Iyer, Brunton represented for partisans a new Plato at the court of a philosopher king, dispensing The Wisdom of the Overself (1943). This doctrine has elsewhere been considered eccentrically mentalist, with elements of Theosophy implied.

A major drawback, in critical estimation, is that the Wisdom teacher opted to claim a Ph.D, enthusiastically advertised by Rider and Company. Brunton’s books were now unassailable, in commercial theory at least. The lofty credential was subsequently revealed to be a deception. When pinned down on the issue, Brunton claimed a Ph.D. from Roosevelt University in Chicago. No record of this credential could be found in university precincts (Masson 1993:161-3).

A “doctoral” certificate later appeared online, dating to 1938. What Brunton actually acquired was a spurious degree from a very commercial correspondence school, on the basis of a short book lacking annotations. This “school” was launched by McKinley-Roosevelt Incorporated, not Roosevelt University. The corporate name of McKinley-Roosevelt University was a rank deception. None of the commercial staff were qualified to teach the numerous subjects for which they received payment from clients like Brunton. The devious and unscrupulous enterprise had to be closed down by the American government in 1947. The superficial tag of Dr. Paul Brunton is meaningless in the academic sense, fitting only the make-believe scenario of fashionable occultism and mentalism.

This presumed esotericist and hermetic philosopher also claimed to reach the end of the spiritual path. At one point, Brunton even called himself Jupiter Rex, signifying king of all the gods. His American secretary defected, becoming a follower of Meher Baba, who claimed the non-academic status of avatar (a Hindu word) from 1954 onwards. The Irani mystic is not associated with royal courts, technology, the British Raj, or Theosophy. He might nevertheless be relevant for study, a consideration which is perhaps even a necessity for the British sector as a foil to Brunton’s caricature. The literature on Meher Baba is now extensive; the primary sources do not include A Search in Secret India.

Bibliography of Works Cited Above

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

——–The Hidden teaching Beyond Yoga (London: Rider, 1941).

——–The Wisdom of the Overself (London: Rider, 1943).

Masson, Jeffrey, My Father’s Guru: A Journey through Spirituality and Disillusion (London: HarperCollins, 1993).

Purdom, Charles, The Perfect Master: The Life of Shri Meher Baba (London: Williams and Norgate, 1937).

——–The God-Man: The life, journeys and work of Meher Baba with an interpretation of his silence and spiritual teaching (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 61

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.