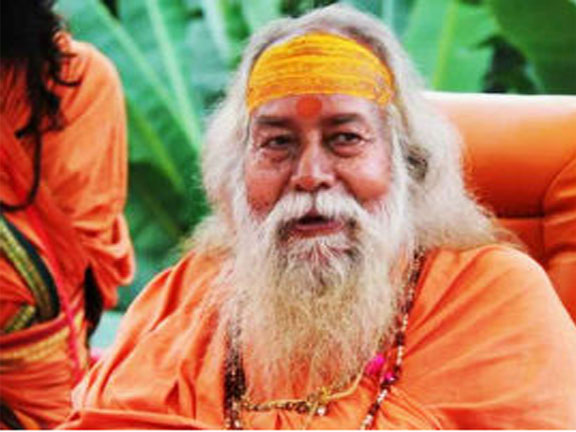

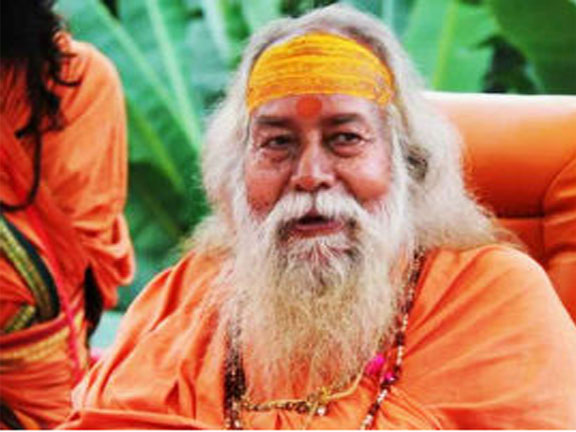

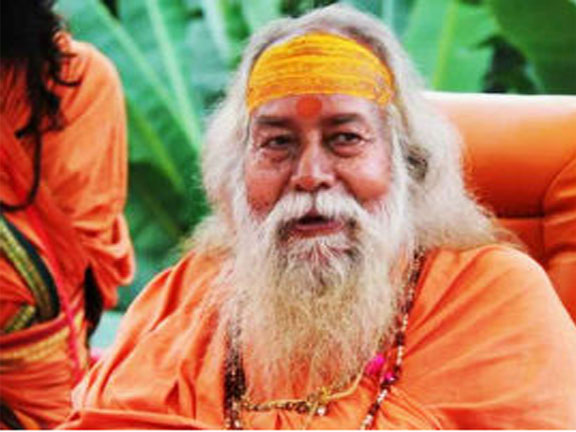

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda SaraswatiIn June 2014, Swami Swarupananda Saraswati commenced an ideological campaign against the deceased Shirdi Sai Baba (d.1918) and his living devotees. Many television newsreels and national newspapers profiled the relevant events.

The Swami is a figurehead of the monastic Shankara Order, whose leaders are known as Shankaracharyas and jagadgurus (Cenkner 1983). In 1973, he became Shankaracharya of the monastery known as Jyotir Math, at Badrinath. In 1982, he also became the Shankaracharya of Dwaraka Math, located in Gujarat. These two monasteries have a high repute, being amongst the five major mathas of the Shankara (or Dashanami) Order. That organisation has strong traditional ballast, reputedly being a continuation of the activity of Shankara, the famous exponent of Advaita Vedanta who lived over a thousand years ago (Pande 1994).

Shirdi Sai Baba

Shirdi Sai Baba was a faqir living at a rural mosque in Maharashtra. He gained an inter-religious following of Hindus, Muslims, and Zoroastrians. This saint often resorted to allusive speech; he was not in any way doctrinaire. Some hagiology does attend his profile; careful investigation of background details is important in such instances. Sai Baba of Shirdi is sometimes confused with Sathya Sai Baba (d.2011), a very different entity who lived in Andhra, claiming to be a reincarnation of the Shirdi mystic.

After the death of Shirdi Sai, temple worship of his image was introduced at Shirdi. Other Shirdi Sai temples also appeared. Swami Swarupananda insisted that Shirdi Sai was a Muslim faqir, not a god or a guru, and therefore could not be worshipped in the manner of a Hindu deity. He declared that images of Shirdi Sai were to be removed from temples. Swarupananda described his campaign in terms of protecting Hindu religion. He urged that Shirdi Sai temples should not be constructed. The critic also described the worship of Shirdi Sai in terms of a conspiracy to divide Hindus. The assertions of this Swami were strongly repudiated by Shirdi Sai devotees. Complaints were already being made against him, in June 2014, at Shirdi, Indore, and Hyderabad.

The disapproving Swami enjoined Shirdi Sai devotees to ensure their purification by fasting on Ekadashi day and bathing in the Ganges. He condemned the government minister Uma Bharti, alleging that she was not a true Rama bhakta after Bharti spoke publicly in support of Shirdi Sai. Swarupananda demanded an apology from Bharti, on the grounds that Shirdi Sai was a meat-eater and did not bathe in the Ganges. He also urged that Shirdi Sai devotees should not worship Rama.

In July 2014, a law court at Indore issued a summons to the Swami, requesting him to appear before the judge, because of a complaint filed against him for making controversial statements. The Swami was able to postpone a legal confrontation for some time thereafter. He meanwhile urged the government to probe an alleged flow of foreign funding into the bank accounts of Sai devotees. Swarupanand insinuated that a foreign power was attempting, in this manner, to distort the sanatana dharma (true religion, i,e, Hinduism). There was no proof or confirmation for that extremist theory.

A degree of conflict occurred between followers of the Swami and devotees of Shirdi Sai. Supporters of Swami Swarupananda notably included Dashanami ascetics or sannyasins, strongly associated with the Shankara monasteries (Clark 2006). The Dashanamis are divided into ten sub-groupings, including the Giris, the Puris, the Bharatis, and Saraswatis. The format has proved complicated for many Westerners to understand, involving different historical phases, and various other ascetic identities. For instance, the Naga (naked) sannyasins, or sadhus, gained a strong militant complexion in former centuries, becoming organised into akharas or “regiments.” They fought in diverse battles, a military scenario which often astonishes readers (Pinch 2006). “The Nagas were also involved in warfare between rival princely states, usually fighting on opposite sides. Moreover, they fought for control of religious centres, since these constituted ever-flowing sources of revenue and solid bases of power” (Hartsuiker 1993:35).

Many of the Nagas cultivated ascetic feats and Yogic practices. Nagas still display weapons, especially the trident (trishul), at religious festivals such as the famous Kumbh Mela. “The Akharas attribute their origin to the great Shankara, an attempt no doubt to gain more respect and credibility” (Hartsuiker 1993:33).

The Baghambari monastery (matha) was strongly influenced by Swami Swarupananda. The leader (mahant) of that monastery was Swami Narendra Giri, who “vowed to deface Shirdi Sai Baba’s temples, and let loose Naga Sadhus on the sect’s followers” (Chandan Nandy, Let Dialogue Prevail, 2014). Many observers in North India feared that the conflict between Nagas and Shirdi Sai devotees could get out of control. Fortunately, this did not happen. However, the tensions were dramatic enough. Indignant Shirdi Sai devotees responded to the threats by burning effigies of Swarupananda in the holy city of Varanasi (Benares).

Swami Swarupananda verbally attacked the Shirdi Sai Baba Trust, based in Shirdi. He accused this body of regarding the Shirdi saint as superior to Hindu deities like Hanuman. In October 2015, the Hindustan Times reported that Swarupananda “also claimed that there were no followers of Sai Baba in the country,” a theme which blatantly contradicted facts. The critic is reported to have described visitors to Shirdi as “mean, selfish and only want their wishes to come true.” The Swami expressed his belief that Hanuman had instructed his followers to build a Hanuman temple near every Shirdi Sai temple, with the intention of driving “the spirit of Sai” out of India.

Shirdi Sai devotees countered the opponent with legal petitions, emphasising his “deliberate intent to hurt religious sentiments.” As a consequence, in September 2015, Swami Swarupananda prudently tendered an apology for controversial statements he had made. He requested Madhya Pradesh High Court to dispose of a petition made against him.

While staying in Bhopal during 2015, the Swami created a poster portraying Lord Hanuman attacking Shirdi Sai with a tree trunk. This pictorial gesture was considered extremist by some Hindu observers. A disciple of Swarupananda was reported, on the media, as saying that the influence of Shirdi Sai would be driven out of India in the next three years by the grace of Hanuman.

In April 2016, The Hindu reported reactions of Shirdi Sai devotees to the orthodox critique. Swarupananda had interpreted the temple worship of Shirdi Sai in terms of creating a drought in Maharashtra. Officials of the Shirdi Sai Baba Trust countered that the Shankaracharya appeared to be suffering from a feeling of insecurity. This was because so many devotees were visiting Shirdi, instead of seeking the darshan of Swami Swarupananda.

The Swami is reported to have said, while staying at Hardwar: “The unworthy Sai is being worshipped while the real Gods are ignored. This is happening in Maharashtra, and particularly in Shirdi. Hence, Maharashtra is facing drought.” Shirdi Sai devotees responded that Swarupananda only wanted publicity. They pointed out that drought was also prevalent in Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and the Punjab. A social worker, active at Shirdi, informed the press that the Sai Baba Trust had donated crores of rupees as charity aid whenever floods, earthquakes, and other calamities had struck Maharashtra and surrounding regions (The Hindu, “Sai Baba devotees fume over Shankaracharya’s remarks,” 2016).

Another pronouncement of the Swami, not relating to Shirdi Sai, was strongly resisted. In April 2016, he complained against the termination of a four hundred year ban on the entry of women to the Shani Shingnapur temple in Maharashtra. Feminists were very indignant at his verdict. A human rights lawyer said that Swami Swarupananda should be charged with contempt of court (Shriya Mohan, “Shankaracharya is a misogynist,” 2016). Swarupananda was contradicting a judgement of the Bombay High Court.

The depiction of Shirdi Sai Baba, as a Muslim outsider to Hinduism, neglects due context of a very liberal attitude on the part of this faqir towards Hindus, and also to the members of other religions (Shepherd 2015). Shirdi Sai was not a preacher or political agitator. He lacked any sectarian bias. In this respect, his eccentricities may be considered refreshing. Shirdi Sai is described by a Western scholar as a Sufi mystic (Warren 1999). However, he did not project any separatist attitude in his predominant encounters with Hindus. His origins are obscure. An influential theory of his Hindu birth at Pathri remains unconfirmed (Kher 2001:1-14).

An account of Shirdi Sai’s devotional following, during the past century since his death, relays that the pilgrims to Shirdi are primarily Hindus, while also including Muslims, Sikhs, and Christians (McLain 2016).

Very much neglected, in Swarupananda’s version of events, is the instance of Upasani Maharaj (d.1941). This entity was a major disciple of Shirdi Sai, subsequently establishing an ashram at nearby Sakori. The brahman saint Upasani is still largely obscure, as a consequence of abbreviated and distorted reports commonly known. A paradigmatic Hindu ascetic, he was completely unwesternised.

During an evocative episode occurring at Benares in 1920, Upasani strongly defended Shirdi Sai, while in bold confrontation with an assembly of orthodox brahman priests and pundits. “He did not deny that Sai Baba was a Muslim, but maintained that the deceased saint was above religious distinctions, existing as much for brahmans as for Muslims” (Shepherd 2005:79). Upasani would not defer to the biases of that prestigious assembly, who were sustaining habitual religious discrimination against Muslims.

Moving to more general matters, some Indian intellectuals have expressed concern at national trends. For instance, the British-Indian sculptor Sir Anish Kapoor referred to a recent development in which “dozens of Indian writers handed back their literary awards in protest, following communal violence against Muslims and attacks on intellectuals” (Anish Kapoor, India is being ruled by a Hindu Taliban, 2015). The “militant Hinduism” of the nationalist Indian government, led by Narendra Modi, was here seen to be at risk of “marginalising other faiths” (ibid). The population statistics in India comprise about 965 million Hindus and 170 million Muslims.

Some Indian writers emphasise the extremely shocking 2002 attack on Muslims (by Hindus) in Gujarat, a tragedy in which “more than 2,000 Muslims were murdered, and tens of thousands rendered homeless in carefully planned and coordinated attacks of unprecedented savagery” (Pankaj Mishra, Gujarat Massacre, 2012).

The long-standing friction between Hinduism and Islam is a disconcerting drawback to Indian cultural unity and the history of religions.

Bibliography:

Cenkner, William, A Tradition of Teachers: Sankara and the Jagadgurus Today (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1983).

Clark, Matthew, The Dasanami Samnyasis: The Integration of Ascetic Lineages into an Order (Leiden: Brill, 2006).

Hartsuiker, Dolf, Sadhus: Holy Men of India (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993).

Kher, V. B., Sai Baba: His Divine Glimpses (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2001).

McLain, Karline, The Afterlife of Sai Baba: Competing Visions of a Global Saint (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016).

Pande, G. C., Life and Thought of Sankaracarya (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994).

Pinch, William R., Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

——–Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2015).

Warren, Marianne, Unravelling the Enigma: Shirdi Sai Baba in the Light of Sufism (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1999; revised edn, 2004).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 71

Copyright © 2017 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati

Swami Swarupananda Saraswati