Hypatia (d.415 CE) was a Greek reared at Alexandria. She is reported to have been proficient in mathematics and astronomy. She is also associated with Neoplatonism, generally credited as commencing in the third century CE. Over a century before her, Ammonius Saccas had taught in Alexandria; this entity is viewed as the effective founder of Neoplatonism. Ammonius was an obscure philosopher, apparently self-taught, who functioned outside the conventional Platonist curriculum. His pupil Plotinus (c.204-270 CE) appears to have shared the same independent orientation. Plotinus moved from Alexandria to Rome, where he lived for the remainder of his life.

According to the early report of Socrates Scholasticus: “Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she [Hypatia] explained the principles of philosophy” (Ecclesiastical History, VII.15). Hypatia apparently rejected Iamblichus, a theurgist who became very influential at that period. According to Damascius (d.540), Hypatia was not satisfied with her father’s knowledge of mathematics. She committed herself to philosophy, publicly interpreting Plato, Aristotle, and others. However, “the precise content of Hypatia’s philosophy can only be surmised” (Hagith Sivan, review of Dzielska 1995).

Hypatia is now one of the most evocative figures in the history of philosophy. Unfortunately, very little historical information about her survives, in contrast to the surfeit of invention created by modern novelists. Her date of birth is a vexed subject, calculations varying from 355 to 370 CE (and later). The early date of circa 355 means that she was of senior age at her death in 415 CE (Dzielska 1995), a more realistic angle than the fictions widely known. Hypatia was violently murdered by street thugs in Alexandria. Questions of context apply to this event. Hypatia is associated (via a parent) with the Great Library of Alexandria, likewise subject to destruction.

The god Sarapis was earlier eliminated in the wave of Christian violence. The Sarapis cult was apparently established as a patron deity for the Ptolemaic Greeks of Egypt, particularly at Alexandria. The Ptolemaic dynasty (prior to the Roman era) subsequently lost enthusiasm for that god. Other cults and religious fashions became prominent (Fraser 1972:278). Ptolemy welcomed large numbers of Jews to Egypt, appointing many of them to high office. The Jewish population of Alexandria increased substantially (ibid:281ff).

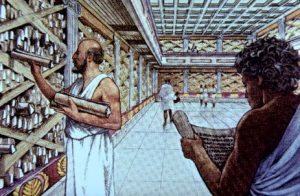

The Great Library of Alexandria

Depiction of the Great Library

The famous Great Library of Alexandria vanished, leaving no trace. Even the architectural style of this edifice is unknown. Built during the reign of Ptolemy II (284-246 BC), the project apparently gained less funding during the Roman era. Diverse interpretation of data relating to the Great Library is “highly controversial.” Very little is reliably known about this institution. There is no direct evidence as to how many libraries existed in Alexandria. Nevertheless, in many fields of science, that city surpassed the achievement of the classical Greek world, and also Rome (Fraser 1972:320ff,336).

In the precinct of the library were two institutions, the Museum and the Library itself, with overlapping purposes but separate jurisdiction – a biblion (or place of books) for scholars and a Mouseion dedicated to the Muses. The precise location remains uncertain. (MacLeod 2004:3)

At Alexandria, Hypatia’s father Theon worked as a mathematician; he produced a new edition of Euclid’s Elements. Theon is associated with the Great Library, being described by some commentators as the last famous member of that institution. A daughter library was located at the nearby temple of Sarapis (Library in the Serapeum). At maximum, the Great Library stored an estimated 500,000 scrolls from different countries. Fraser assessed the holdings at about 490,000 papyrus scrolls; the more traditional figure was 700,000 (Thiem 1979:508). The scrolls represented Greek, Hebrew, Babylonian, and Egyptian heritages.

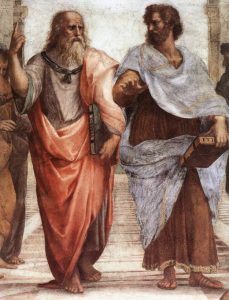

The Museion is described by Fraser as a cult centre intended for worship of the Muses. Greek cities often included a Museion. These shrines were primarily extensions of a literary society, which assembled to hold literary competitions in the shrine. A priest of the Muses presided. During the Roman era, those shrines developed into secular centres of learning, the ancient equivalent of a university. The Museion at Alexandria gained high prestige, deriving from an earlier association of the Muses with philosophy. This association perhaps commenced with Pythagoras, being greatly developed during the fourth century BC. The Academy was apparently organised by Plato as a body of persons associated for a religious purpose, the service of the Muses (this auspice being necessary to gain conventional approval). Evidence that the Lyceum was similarly organised is substantial, although in the Peripatetic tradition, the natural sciences gained predominance over literary activities (Fraser 1972:312ff).

The early research standard of the Library, during the Ptolemaic era, apparently declined in subsequent centuries. A lack of data about the personnel is lamented. Some modern commentators infer a lack of patronage; others suggest that library residents were wealthy men with political influence. According to Fraser, the mere fact that the Great Library was much frequented does not prove that the learning was of a high standard (ibid). At an early date, Timon of Phlius (d.230 BC) is well known for his depreciatory assertion: “In the populous land of Egypt many are they who get fed, cloistered bookworms, endlessly arguing in the bird-coop of the Muses” (ibid). Timon was a Pyrrhonist philosopher and a composer of satirical poetry. He was influenced by a Cynic mode lampooning vanity and dogma.

The factor of two libraries at Alexandria might assist to explain various traditions of three major conflagrations. First, Julius Caesar may have inadvertently burned all or part of the Museion library in 47 BC. Second, the Emperor Theodosius may have provoked the burning of the Serapeum library at circa 390 AC. Third, the Caliph Omar may have ordered the burning of a residual library at circa 642. Specialist scholars have disputed each of these burnings. The posited Arab event has been doubted by most scholars (Thiem 1979:508).

A Neoplatonist Situation

“Teaching in the Plotinian tradition of Platonism, Hypatia attracted elite students of diverse religious affiliations” (Brakke 2018). A sceptical view suggests that Hypatia was basically a Ptolemist rather than a Platonist (Bernard 2010:417). The letters of her famous student, Synesius of Cyrene, “do not contain a single explicit mention of Hypatia’s philosophical allegiance” (ibid:418). The extent to which she was taught by her father Theon is not clear (ibid:419).

None of her writings on philosophy survive. Her mathematics has been reconstructed. According to some commentators, Hypatia viewed geometry as a route to the One (a Neoplatonist objective). This outlook was compatible with celibacy. Astronomy was still a sacred science in her time, often admixed with astrology (which Plotinus rejected). Hypatia was apparently proficient in astronomy, even teaching how to design an astrolabe, a portable brass calculator about six inches in diameter, also helping to determine the hour of day.

Modern scholarship has concluded that Hypatia did not teach theurgy lore, pervading so much of the later Neoplatonism associated with Iamblichus and Proclus. She is instead viewed as a Neoplatonist in the Plotinian sense; an early annalist refers to her in a context of the tradition of Plato and Plotinus. Like Plotinus, her lifestyle was frugal and disciplined; she never married, remaining a virgin. Female philosophers were a rarity. There were a few women amongst the pupils of Plotinus, but they reaped obscurity.

The fifth century annalist Socrates Scholasticus (c.379-450) was a contemporary Greek Christian of Constantinople. His Ecclesiastical History profiles Hypatia as a major philosopher of the time, referring to her as following the Platonist way of thought via Plotinus. Professor J. M. Rist suggested that Hypatia revived interest in Plotinus at Alexandria.

The Platonist curricula relied on students from wealthy families. Hypatia was no exception. Her pupils came from various towns in Egypt, also from further afield in Syria, and even distant Constantinople. There were Christians in her circle; two of these became bishops, including Synesius of Cyrene (d.413), a Greek Platonising Christian who was at first reluctant to become Bishop of Ptolemais (however, he did so in 410).

This was a difficult time for the surviving paganism, now increasingly the minority in lands ruled by Christianity. Persons from wealthy Christian families still learned Greek philosophy. However, theological dominance meant that Platonism and Neoplatonism were on the defensive, both at Alexandria and Athens. In the early fourth century CE, nearly 2,400 temples existed in Alexandria. That means roughly one temple for every twenty houses (Watts 2017:9). Nevertheless, Christians rapidly gained the upper hand. The divide was pronounced, in social terms, between many of the townspeople and the Graeco-Roman upper class.

Hypatia lived largely in an Alexandria dominated by wealthy, well-educated, Greek-speaking city councillors who owned luxurious townhouses and enjoyed urban gardens. She died at the hands of people who lived in a different Alexandria. Theirs was a dirty, dangerous, and often disgusting city that offered none of the space or security that Hypatia enjoyed. (Watts 2017:7)

Hypatia was murdered by a low class mob. There are different versions of her death in the antique reports. “Each author has his own version of these events, most often related to a moral apologue” (Bernard 2010:418). With regard to more recent Hypatia literature, scholarship has to be distinguished from novelism. Eighteenth century writers like Voltaire and Gibbon stand accused of creating a literary legend. Nineteenth century embellishments followed. The twentieth century added a further round of Hypatia lore influenced by contemporary preference. “Many resurrections of Hypatia are often idealised and romanticised” (Birkman, n.d.).

An early sixth century report was supplied by Damascius, a Neoplatonist who studied in Alexandria two generations after the death of Hypatia. This source affirms that Hypatia gave public lectures on Plato and Aristotle. More ominously, the Alexandrian Patriarch Cyril (in office 412-44) became envious of Hypatia, plotting her murder.

Cyril was a Christian Archbishop (or Patriarch) who later gained repute as the persecutor of pagans. He also opposed Jews and heretics. Hypatia was on cordial terms with the governing secular prefect Orestes, a rival of Cyril in the political power stakes, an official who resisted clerical attempts to gain secular control. Orestes was a Christian; thus the issue was not paganism versus Christianity, but civic versus ecclesiastical interests. Hypatia might have expressed some degree of opposition to the church hierarchy. However, she was not anti-Christian and cared for her Christian students, who perhaps included Orestes.

Violence at Alexandria

From the late third century CE, recurrent violence was a major problem at Alexandria. “Repeated violence created a volatile atmosphere in which mob action could easily be incited, whatever the cause, real or imaginary” (Whitfield 1995:16).

Christianity became the official religion of Alexandria, agitating against the pagan and Jewish inhabitants. Street fights were frequent by 364 CE. In this ongoing struggle, much of the content in the Great Library was destroyed. The damage apparently culminated in 391, when Archbishop Theophilus destroyed all pagan temples, under orders from the Roman Emperor. Theophilus eliminated the temple of Serapis, which may have accommodated the last library scrolls. In 412, Theophilus was succeeded as Patriarch by his nephew Cyril (376-444), whose political rival was Orestes, Roman prefect of the city (meaning leader of the civil government).

The struggle for urban power climaxed in a massacre of Christians by Jewish extremists. In retaliation, Cyril led a mob against the synagogues, inviting his followers to loot these religious centres. Many Jews were expelled from Alexandria, their homes being pillaged. The indignant Orestes protested to the Roman government at Constantinople. Cyril then summoned hundreds of orthodox Coptic monks from Nitria, persuading them to take action. Supporters of Cyril then tried to assassinate Orestes, who protested that he was a baptised Christian. The agitators confronted Orestes in the street, while he was riding his chariot. A man named Ammonius hit the prefect with a stone he threw. The attacker was captured by Orestes and tortured to death in a public spectacle.

Roman tortures were notorious, the victims generally being low class people and slaves. Many Coptic Christians had suffered those tortures, imposed by the upper class Graeco-Roman colonialists. Many Coptic monks were low class men (some of the earlier ones were apparently ex-Egyptian priests). Crucifixion, being thrown to lions, and immersion in boiling oil were only three of the elitist afflictions in the Roman Empire. Wheel breaking and the rack were horrific additions to the ancient ordeals of agony favoured by Rome.

The Coptic population resented Roman colonialism. The Diocletian persecution exercised a harsh repression in Egypt. Over 600 Christians were reputedly killed at Alexandria during the period 303-311. Subsequently, during the fourth century CE, Christian virgins (parthenoi) in Egypt are known to have been publicly scourged and imprisoned by the high class Greeks and Romans, whose “contempt for inferiors and slaves is not attractive; many Copts must have loathed the sight of them” (Christian Virgins). In 359/60, the Alexandrian virgin Eudemonis was “cruelly tortured” by imperial officials, including Duke Artemius (Brakke 1995:130). This was a sequel to earlier afflictions. Numerous parthenoi lived at Alexandria, of diverse social background. “Some were wealthy, owning property and slaves, while some of the less elevated were themselves slaves” (article last linked above). Hypatia may likewise have owned slaves, a common acquisition of the colonial upper class.

The identity of the tortured victim Ammonius is confused. He may have been one of the Parabalani, not a Nitrian monk as is sometimes claimed. The former were low class assistants of Cyril in the city. Some fifteen years earlier, Archbishop Theophilus persecuted about 300 liberal monks of Nitria as heretical Origenists. Theophilus actually marched against these monks with his soldiers. The attackers burned the huts of the monks, who were taken prisoner and ill-treated. The dispossessed party fled to Palestine. Their teachings included allegorical explanation of the Resurrection and pre-existence of the soul (an Origenist theme associated with reincarnation). Church officials were resistant to Origenists, whose teaching ran counter to such orthodox doctrines as creation of the world ex nihilo. The bishops increasingly encouraged literal exegesis amongst the monks, creating an insular mood of dogmatism that was easy to manipulate by ecclesiastics.

Hypatia became part of the political struggle, when rumours of a pact with Orestes incited hostility against her. She was killed by a Christian mob, apparently while lecturing in a public place. She may have been a random victim of the violence (Donovan 2008:13). The earliest and most reliable account is that of Socrates Scholasticus (d.450), who was writing about 25 years after her death. His Ecclesiastical History relates that Hypatia had frequent meetings with the imperial prefect Orestes. As a consequence, Christians believed that she prevented Orestes from being obedient to Cyril. A mob, under the leadership of Peter the Lector, dragged Hypatia to the church called Caesareum, where she was brutally murdered, her corpse being burnt.

Some commentators have attributed the murder of Hypatia to Christian monks. That is a theory, not proven fact. A more pressing interpretation is that Christian laymen were the murderers. Some scholars emphasise that Cyril utilised a private cadre known as the parabalani (parabolans). This grouping comprised about 800 young men employed by the Alexandrian Patriarch in the service of the church. The parabalani were recruited from the lower classes, sometimes serving as bodyguards. They have been compared to a brigade of ambulance personnel, removing lepers and other helpless persons from city streets for treatment in Christian hostels. The parabalani are described in terms of tough, low class Christian social workers. They may have included minor clerics or dependents of monasteries. They had to be “poor and representative of the entire city’s indigenous population” (Bowersock 2010).

It looks as if the miscreants who destroyed Hypatia all came from the ranks of [the] city’s poor, and all owed their services under the patriarch to enrollment in a charitable organisation dedicated to helping the needy and the sick. (Bowersock 2010:45)

The parabalani are described, by some scholars, as soldiers in the private army of Cyril. They were the most likely tool of the former Patriarch Theophilus in the earlier destruction of the Serapeum and other pagan temples. This cadre were almost certainly involved in the fanatical attack on the Jewish quarters at Alexandria in 414, a molestation inseparably associated with Cyril.

Professor Maria Dzielska concluded that these young men were incited to spread adverse rumours about Hypatia, subsequently causing an Alexandrian mob to kill her in 415 (Dzielska 1995). She was depicted as a witch; the unreasoning attitude is evident in a seventh century version of events by Bishop John of Nikiu, who describes Hypatia as a witch deserving to be killed.

Writing over a century after Hypatia’s death, the pagan philosopher Damascius (d.540) says that Cyril plotted her murder. Violent men killed her; no identity for these men is supplied. The source is Philosophical History, a work of Damascius surviving only in reconstruction from fragments. Content relates to the contemporary Neoplatonists of Alexandria and Athens (Athanassiadi 1999). A brief report of Hypatia was here included, later reproduced in the Byzantine Suda, a compilation which erroneously describes her as the wife of Isidore of Alexandria (c.450-c.520). This philosopher was born after her death; hindsight can too easily blur details. More reliably, Isidore reluctantly accepted the Athenian succession (diadoche). The Athenian school was closed down in 529 by the hostile Emperor Justinian.

While some commentators conclude that Cyril was responsible for the death of Hypatia, others blame the violent tendencies of Alexandrians on a more general basis. Christian rioters afflicted some of their own bishops in the same callous manner.

Interpretation

A late seventh century source is John, Bishop of Nikiu, whose Chronicle reflects a theological bias against Hypatia. Many centuries later, the sceptic Voltaire employed the figure of Hypatia as a means to attack the Christian church. History can be elusive in ideological programmes.

“Her mutilation in the streets of Alexandria has generated a continuing violence at the hands of numerous historians” (Whitfield 1995:14). Villains are here identified as Charles Kingsley, Edward Gibbon, and Carl Sagan. These writers gave the impression that philosophy was snuffed out by Christian bias. They ignored a significant continuation of the Alexandrian philosophical tradition over the generations prior to Islam.

The typical discussions of Hypatia’s death are characterised in terms of (a) overstating the role of Cyril (b) ignoring the continuation of Alexandrian Neoplatonism after 415 CE (c) misrepresenting Hypatia as an opponent of Christianity (Whitfield 1995). A preference to depict Cyril as the agent of murder is now popular. However, the Suda relays that some parties attributed the murder to a seditious tendency amongst Alexandrians.

Damascius has been accused of depicting Hypatia as a martyr of Hellenism. Edward Gibbon (1737-94) was eager to vilify Cyril in his defence of paganism against Christianity. His Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire gained both partisans and critics. Gibbon’s principal source for Hypatia was the Suda, a tenth or eleventh century Byzantine lexicon of orthodox complexion. In other instances, Protestant writers employed Hypatia as a literary weapon in their polemic against Catholicism. Charles Kingsley continued the anti-Catholic stance in his novel Hypatia, or New Foes with an Old Face (1853).

Professor Rist drew attention to the problem created by Gibbon, whose account of Hypatia was designed to arouse “emotional hostility” to Christianity (Rist 1965). Bertrand Russell approvingly quoted from Gibbon’s narrative, adding in his own words: “After this, Alexandria was no longer troubled by philosophers” (Russell 2000:365). The British analytical philosopher has been strongly criticised for his failure to register the ongoing tradition of Neoplatonism at Alexandria after the death of Hypatia. The complement was substantial (Watts 2006).

Professor Dzielska speculates on the subject of why Hypatia stopped writing to her Christian associate Synesius of Cyrene. This theme suggests that the philosopher had changed her earlier non-political stance via her liaison with Orestes. The indications are that Hypatia was accepted in some liberal Christian circles, not being an agitator against religion. She wore the tibon, a cloak associated with Cynic philosophers, a category to some extent tolerated by Christians. The cloak is awarded another interpretation:

The tibon was something like a distinguished professorial toga, as distinct from the earlier short, rough-woven, threadbare Doric cloak of peasants or such philosophers as Socrates or the Cynics. (Dzielska 2013:70)

Soon after the death of Hypatia, the alarmed city council of Alexandria made repeated petitions to the court at distant Constantinople. They wanted imperial intervention in the scenario of violence. Moreover, a widespread reaction emerges:

Christians throughout the [Roman] empire erupted in condemnation of Cyril and the Alexandrian church for the ways in which their leadership had enabled such uncontrolled violence. Because this violence happened on his watch, the murder of Hypatia apparently ended the public career of Orestes. (Watts 2017:3)

As a consequence, the following year (416) Cyril was divested of his authority over the parabalani, whose numbers were reduced to 500 by an imperial ordinance. The gesture to public order is deemed superficial in some accounts. Only two years later, Cyril regained his leadership of the parabalani. However, the imperial ordinance restricted the movements of this grouping, who were prohibited from public places like theatres and courts. Their terrorist potential was now effectively disabled. Nevertheless, Cyril gained ascendancy in the political climate.

Aftermath

The death of Hypatia did not mean the termination of classical education at Alexandria. Philosophical instruction continued in this city until the Arab invasion (Brakke 2018). The ongoing Alexandrian tradition included Ammonius (d.526) and Olympiodorus (d.c.570). Ammonius, a commentator on Aristotle, was skilled in geometry and astronomy. He may have been coerced to pay lip service to Christianity via an arrangement with the Bishop. His strategy ensured survival. Olympiodorus taught both Aristotelian and Platonist doctrines during a period when the number of Christian students in this school greatly increased. Classes in rhetoric and philosophy were a means for young Christian students to enter the clergy or serve in the Byzantine court. The Neoplatonist school at Athens was closed in 529 by Justinian; the Alexandrian counterpart fared much better. Despite strictures, a classical education was considered essential for Christian theology.

A leading scholar emphasised that Hypatia continues to be a subject for novelists and playwrights. The annual spate of literary fiction is regarded by some as a distraction with tendentious content. In new age fantasy lore, Hypatia has been contacted by a spiritualist medium. The many inaccuracies in the film Agora are no reason to applaud commercial misrepresentation (Dzielska 2013).

Bibliography:

Athanassiadi, Polymnia, Damascius: The Philosophical History (Athens: Apamea Cultural Association, 1999).

Bernard, Alain, “The Alexandrian School: Theon of Alexandria and Hypatia” (417-436) in Lloyd P. Gerson, ed., The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity Vol. One (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Birkman, Gabrielle, Hypatia: The First Female Mathematician, Scientist, and Philosopher (n.d., academia.edu, online).

Booth, Charlotte, Hypatia: Mathematician, Philosopher, Myth (Stroud: Fonthill Media, 2017).

Bowersock, Glen W., “Parabalani: A Terrorist Charity in Late Antiquity,” Anabases (2010) 12:45-54.

Brakke, David, Athanasius and the Politics of Asceticism (Oxford University Press, 1995).

——–“Hypatia,” Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia, 2018 (online).

Deakin, Michael A. B., Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr (New York: Prometheus, 2007).

Donovan, Sandy, Hypatia: Mathematician, Inventor, and Philosopher (Minneapolis: Compass Point, 2008).

Dzielska, Maria, Hypatia of Alexandria, trans. F. Lyra (Harvard University Press, 1995).

——–“Once More on Hypatia’s Death” (65-74) in Dzielska and K. Twardowska, eds., Divine Men and Women in the History and Society of Late Hellenism (Cracow: Jagiellonian University Press, 2013).

Fraser, P. M., Ptolemaic Alexandria (3 vols, Oxford University Press, 1972).

MacLeod, Roy, ed., The Library of Alexandria: Centre of Learning in the Ancient World (London: I. B. Tauris, 1999; new edn 2004).

Rist, J. M., “Hypatia,” Phoenix (1965) 19(3):214-225.

Russell, Bertrand, History of Western Philosophy (1946, second edn, 1961; London: Routledge, 2000).

Thiem, J., “The Great Library of Alexandria Burnt: Towards the History of a Symbol,” Journal of the History of Ideas (1979) 40:507-526.

Watts, Edward J., City and School in Late Antique Athens and Alexandria (University of California Press, 2006).

———Hypatia: The Life and Legend of an Ancient Philosopher (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Whitfield, Bryan J., “The Beauty of Reasoning: A Reexamination of Hypatia of Alexandria,” The Mathematics Educator (1995) 6(1):14-21.

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

Depiction of Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens, by Raphael

Depiction of Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens, by Raphael