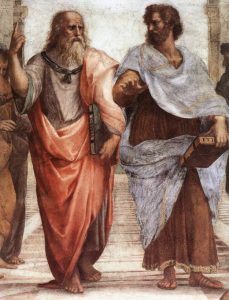

Depiction of Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens, by Raphael

Depiction of Plato and Aristotle, The School of Athens, by Raphael

The most well known disciple of Plotinus was Porphyry (c.232-c.305 CE), a Phoenician from Tyre, whose parents are often described as Syrians. Before meeting Plotinus, he originally studied at Athens under the Platonist Longinus. Possessing the disposition to study different languages and religions, he developed a polymathic ability.

When Porphyry moved to Rome in 263, he became a pupil of Plotinus. He was at first disconcerted by differences with the “official” Athenian format. The method of Plotinus contrasted with that of Longinus. Plotinus was far more informal and unorthodox. Longinus had composed two works of note; however, Plotinus classified him as a scholar or literary man, not as a philosopher.

Plotinus did not write commentaries on Plato; his exposition, preserved in the Enneads, was in the Platonist spirit but altogether more free-ranging. Both he and Longinus had been students of the deceased Ammonius Saccas in Alexandria. They were nevertheless in disagreement. Porphyry at first expected technical perfectionism from Plotinus. He found instead that Plotinus was not concerned about grammatical niceties in his usage of Greek. Like Ammonius, Plotinus was outside the official Platonist curriculum, whereas Longinus had become part of this convention.

Porphyry inherited the private manuscripts of Plotinus, which he considered defective in terms of format, though not in respect of ideational and experiential content. Porphyry eventually edited those manuscripts, publishing the result some thirty years after the death of his teacher. The Plotinus texts became known as the Enneads.

The output of Porphyry is different to that of Plotinus. He was an industrious writer, evidently believing in a reconcilement of the teachings of Plato and Aristotle. Porphyry wrote commentaries on Aristotle that Plotinus might have deemed too academic. These included the famous Isagoge, a preparation for the study of Aristotelian logic, well received by the Christian Schoolmen centuries later.

About sixty works are attributed to Porphyry. Most of these are lost or extant in a fragmented form. The subjects covered include history, mathematics, Homeric literary criticism, and metaphysics. There are scholarly uncertainties in confirming a number of the attributions.

The uncertainties have contributed to a mixed assessment of Porphyry’s role. He may have deliberately composed for different readerships, given the diverse nature of attributions. Modern scholars have credited Porphyry with a basically rational orientation. However, he diverged into what some commentators have deemed an idiosyncratic preoccupation with religious matters (and even astrology).

One view is that he validated the Chaldean Oracles for the common worshipper, while himself remaining aloof from theurgy. Augustine of Hippo presented Porphyry in terms of an anomaly; Pierre Hadot concluded that Porphyry tried to find a universal denominator in varied religious phenomena, including the Indian “gymnosophists.”

His lengthy work Against the Christians survives only in fragments; this critique was denounced by Christianity, being burned in 448 by Byzantine decree. Porphyry was a defender of paganism, more specifically the philosophical tradition of Plato and Aristotle. During his lifetime, the spread of Christianity was slow by comparison with fourth century developments after the reign of Constantine.

One aspect of his mentation was a “Pythagorean” disposition associated with vegetarianism, which he advocated in the treatise On Abstinence from Killing Animals. Like Plotinus, Porphyry believed in a contemplative and ascetic lifestyle. Nevertheless, at about the age of sixty, he married Marcella, whose interest in philosophy was commemorated in his Letter to Marcella.

Perhaps the most evocative writing of Porphyry is the Letter to Anebo, extant in fragments. This work has been assessed in terms of critical reference to the ritualist version of Mysteries, as a device to turn the attention of distracted readers to philosophy. The anonymous epistle is addressed to an Egyptian priest. The author was evidently averse to divination and theurgy.

The Letter to Anebo complains about Egyptian religion, and the priests who acted as astrologers, teaching an inflexible astrological fatalism. The document has been interpreted as an attack on Iamblichus, apparently a former pupil of Porphyry, who became an influential advocate of theurgy.

Iamblichus (c.245-325) is a disputed subject. “Hailed by some as the most sublime and dazzling metaphysician who changed the course of Platonism, he is deprecated by others as the most obscure though prolific author, who imported into his texts all sorts of superstition, oriental beliefs and magic, and eclectically fitted all this into his own bewildering metaphysical schema with a heavy reliance on triadic subdivisions” (Afonasin et al 2012:1).

A Syrian from a wealthy family of aristocratic association, Iamblichus taught a version of Neoplatonism at the Syrian town of Apamea. He was an enthusiast of Pythagoras, whom he revived in a theurgic context that is controversial. In his De Vita Pythagorica, Iamblichus attempted a new programme for philosophy via his interpretation of the Pythagorean way of life. The De Vita “can be seen as a kind of protreptic summation of the whole ethical tradition of Greek philosophy, a tradition in which all the schools agreed that philosophy was not simply a set of doctrines, but a whole way of life” (Dillon and Hershbell 1991:29).

Iamblichus is credited with authorship of On the Mysteries (De Mysteriis); the attribution has not been universally accepted. That treatise was composed under the pseudonym of Abammon, signifying a putative Egyptian priest. De Mysteriis was evidently intended as a response to Porphyry’s anti-theurgy composition. Iamblichus here “concentrates on highlighting the signs by which Porphyry would be able to recognise true theurgy when he sees it, and argues that the only way Porphyry will gain the understanding which he seeks is by participating in the divine rites” (Clarke et al 2003:xlix-l).

There is no doubt that the issue of theurgy was attended by a strong disagreement. Porphyry was furthering the outlook of Plotinus on this point, while Iamblichus and his school were in support of ritual sacrifices, divination, trance, invocations, ritual mysteries, talismans, and other trappings.

This issue remains an important significator of orientation, both in respect of the Neoplatonist exemplars and the contemporary responses.

Bibliography

Afonasin, Eugene, John Dillon, and John F. Finamore, eds., Iamblichus and the Foundations of Late Platonism (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

Barnes, Jonathan, trans., Porphyry: Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2003).

Clark, Gillian, trans., Porphyry: On Abstinence from Killing Animals (Cornell University Press, 2000).

Clarke, Emma C., John M. Dillon, Jackson P. Hershbell, trans., Iamblichus: De Mysteriis (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003).

Dillon, John, and Jackson Hershbell, ed. and trans., Iamblichus: On the Pythagorean Way of Life (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 1991).

Finamore, John F., and John M. Dillon, Iamblichus, De Anima: Text, Translation, and Commentary (Leiden: Brill, 2002).

Hoffman, R. Joseph, Porphyry’s Against the Christians: The Literary Remains (New York: Prometheus, 1994).

Smith, Andrew, Porphyry’s Place in the Neoplatonic Tradition (The Hague: Nijhoff, 1974).

Wallis, R. T., Neoplatonism (London: Duckworth, 1972).

Wicker, Kathleen O’Brien, Porphyry the Philosopher: To Marcella (Atlanta: Scholar’s Press, 1987).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

October 10th 2011, modified October 2021

ENTRY no. 43

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.