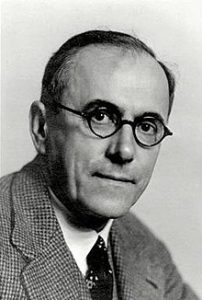

Meher Baba, 1950

The subject of Meher Baba (1894-1969) has dimensions that are frequently missing in standard portrayals. The factor of Zoroastrian background is relevant. However, Meher Baba did not teach Zoroastrian doctrines. This matter has caused confusion, leading some people to mistakenly believe that he taught Hinduism.

His ancestors came from the Yazd plain in Central Iran, a region notable for one of the two surviving Zoroastrian populations in that country. The Zoroastrian minority in Iran were afflicted with stigmas imposed by Shia Islam. Many Irani Zoroastrians chose to emigrate. The father of Meher Baba, namely Sheriar Mundegar Irani (1853-1932), was initially trained as a salar, or custodian of a local dakhma (burial place). Sheriar emigrated to India, eventually settling at Poona (Pune), where he gained literacy in Arabic and Persian (and reputedly Hebrew). His son Merwan Irani (Meher Baba) was born at Poona.

When he was nineteen, Merwan became a follower of Hazrat Babajan (d.1931). This Pathan matriarch lived under a tree at Poona (Shepherd 2014). The faqir Babajan exerted a strong influence upon the young Irani, who became inwardly absorbed and oblivious to his surroundings. Orthodox Zoroastrians were averse to Babajan, because she was a Muslim. These critics regarded Merwan’s unconventional and neutral tangent as aberrant.

Meher Baba created an ashram at a desolate site becoming known as Meherabad, situated a few miles south of Ahmednagar, a city in the Maharashtra territory. In 1925 he commenced silence, one of his major distinguishing characteristics. There was no vow involved; he merely continued his silence year by year. For communication purposes, he resorted to the use of an alphabet board, featuring letters of the English language.

His ashram contingent became known as mandali, many of them Zoroastrians. Wearing ordinary clothes, they did not resemble the staff of Hindu ashrams. Strongly opposed to caste distinctions, Meher Baba supported the untouchables (Dalits). He generally restricted facilities for darshan, meaning public audience, which he evidently regarded as an interruption. There should be no confusion with some well known Hindu gurus, who tended to favour daily darshan and a considerable number of attendees.

Opposition to Meher Baba, from orthodox Zoroastrians, was strong during the 1920s. They did not actually know what he taught. His discourses to devotees were privately recorded, and not publicly available. He is on record as referring to Zarathushtra (Zoroaster), but not in the conventional religious sense. Some analysts have described his teaching as eclectic. However, adequate analysis has scarcely begun.

In the late 1920s, Meher Baba conducted a school for boys known as Meher Ashram. The inmates included Hindus, Muslims, and Zoroastrians. In 1929, he undertook a visit to Iran. Some acclaim occurred at Yazd, where he was welcomed by both Shia Muslims and local Zoroastrians. Despite the enthusiasm in evidence, Meher Baba declined to meet the Shah of Iran, instead ending his tour with a renewed incognito policy (Shepherd 2005:116-120).

In 1931, he commenced a series of journeys to Europe and America, ending in 1937. In 1932, some of his British devotees desired publicity for his arrival in London. He consented to their request, briefly appearing on a Pathe newsreel with Charles Purdom. His first visit to England (the previous year) had been conducted without publicity. He resumed his standard incognito approach after the “world tour” in 1932. Meher Baba evidently did not desire public profile. Numerous private photographs attest the incognito tendency of this Irani mystic. He frequently wore a Western suit; contemporary European headgear concealed his long hair.

The major critic of Meher Baba was a British occultist with a disposition for Yoga. Paul Brunton (d.1981) gained commercial status with a popular book entitled A Search in Secret India (1934). Some contents of this narrative do not withstand critical examination. Brunton gives a distorted and partial version of some events in 1930-31. He subsequently encountered Charles Purdom (d.1965), a major British supporter of the Irani. Purdom relates how Brunton complained to him that Meher Baba could not perform a requested miracle, and therefore Baba was a fraud (Purdom 1964:128,440). Brunton’s publisher eventually advertised his identity in terms of Dr. Paul Brunton. This credential also proved misleading, being derived from a correspondence course that was closed down by the Federal Trade Commission. The critique of Brunton by Dr. Jeffrey Masson is revealing (Masson 1993).

A new project in 1936 was the Rahuri ashram for the mad. This activity underlines the philanthropic dimension of Meher Baba’s outlook. He personally ministered to the mad, plus other inmates, of this unusual ashram (Donkin 1948:95-104). One of his daily tasks was “to scour the ashram latrine” (ibid:96), an accomplishment seldom in evidence amongst gurus. During subsequent years, he created seven temporary centres which have been called “mast ashrams” (ibid:105-149). These phenomena have no known relation to any aspect of the Hindu ashram tradition.

During the Second World War, and also later years, Meher Baba was active in a distinctive undertaking known as “mast work.” The masts were Indian saints and related examples of a “God-intoxicated” category. Meher Baba sought out many of these entities (both Muslims and Hindus) in arduous journeys undertaken throughout India. He was assisted by Baidul Irani and other Zoroastrian mandali. The commitment is notable for a complete absence of publicity. There is no known counterpart of this activity in the careers of Hindu gurus. The mast work was reliably documented by a British medical doctor (Donkin 1948), who became one of the mandali.

The subsequent New Life phase has often caused perplexity. Commencing in 1949, Meher Baba described this phase in terms of a “new life of complete renunciation and absolute hopelessness.” The New Life opened with his injunction that “no one should try to see Baba or his companions for any reason whatsoever, as Baba will not see anyone of them, nor allow his companions to do so” (open communication via Adi K. Irani dated October 1949). This was another incognito exercise.

A further development has been the subject of misunderstandings. In 1952, Meher Baba applied his signature to a Charter for the American organisation known as Sufism Reoriented. The leader of that contingent was Murshida Ivy O. Duce, who became his devotee. Meher Baba did not compose the Charter, but checked the content and made suggestions. At this period, he made clear that his approach was neutral to all religions, also that contact with him could be made independently of all “isms.”

Murshida Duce claimed that Meher Baba promised, for Sufism Reoriented, a perpetual series of illumined murshids for centuries to come (Duce 1975:123). This extravagance was strongly contradicted by her dissident colleague Don Stevens, who soberly emphasised that Meher Baba never made any such promise.

During the early 1950s, the Irani mystic gained many new Hindu devotees in Hamirpur and Andhra. He undertook darshan tours in both of those regions; he had formerly declined repeated requests, made since 1947, to visit Andhra. During a darshan tour in 1954, for the first time he publicly affirmed his role as “avatar of the age.” This avatar identity is the most controversial aspect of his career. Meher Baba had made private references to such a role in former years. “He was well aware that avatars are as common as mud in India, and was known to remark that they exist in every other village. To the best of my knowledge, a Zoroastrian avatar on Indian soil is unique” (Shepherd 1988:50).

Meher Baba suffered two motor accidents, in 1952 and 1956. He himself did not drive a car. The second accident left him with an injured hip that affected his walking ability. His last years were spent in retirement at Meherazad, his second ashram near Ahmednagar. There was a more convivial extension each summer at the venue known as Guruprasad, in Poona. Visiting devotees generally went to Poona, attending sahavas programmes which Baba at times permitted.

Extant films reveal situations at Meherazad and Poona. The most significant film, with a soundtrack, dates to 1967. This is the Gasteren footage Beyond Words. Meher Baba is here shown bathing lepers at Meherazad, and also reiterating his well known warning against the use of drugs. In his various messages, LSD and cannabis were both targeted as harmful distractions.

Hindu gurus were not noted for imparting any such message. Some observers say that the Hindu perspective on drug issues was compromised by a widespread usage of cannabis amongst the sadhu population in India. Whatever the case here, Meher Baba did not hestitate to criticise the psychedelic holy men, whose tendencies he described in terms of a recurring (or perennial) problem.

Meher Baba died in January 1969 at Meherazad, while suffering severe muscular spasms. His condition was a source of puzzlement to medical doctors in attendance. The medics said that he should have been in a coma, but he showed no sign of mental disturbance. His body was buried on Meherabad Hill, where a tomb had been constructed many years before.

After his death, the surviving mandali presided at the ashrams of Meherabad and Meherazad. The chief spokesmen were Adi K. Irani (d.1980) and Eruch B. Jessawala (d.2001). In 1980, a disagreement arose between Eruch and Sufism Reoriented. Eruch agitated against the new Murshid of that organisation, namely James Mackie (d.2001), whom Ivy Duce had appointed as her successor. For several years during the 1980s, in reaction to mandali critique, the supporters of Mackie stopped visiting the ashrams and the tomb of Meher Baba.

The mandali are now extinct. Some devotees refer to the current phase in terms of “post mandali” events. Eruch and his colleagues certainly did exercise a strong influence upon devotees at large. Mandali views were frequently represented as authoritative.

The sources on Meher Baba are many and varied. Considerable diligence is now required in tracking all the documentation. I contributed the first critical bibliography (Shepherd 1988:248-297). By far the longest work available is Lord Meher (Meher Prabhu), a multi-volume biography. That celebration is commonly attributed to Bhau Kalchuri, of the mandali. However, Kalchuri was only one of the authors/compilers at work in this project. A number of errors can be found in the Reiter edition, partly arising from the translation efforts involved.

Bibliography:

Brunton, Paul, A Search in Secret India (London: Rider, 1934).

Deitrick, Ira G., ed., Ramjoo’s Diaries 1922-1929 (Walnut Creek, CA: Sufism Reoriented, 1979).

Donkin, William, The Wayfarers: An Account of the Work of Meher Baba with the God-intoxicated, and also with Advanced Souls, Sadhus, and the Poor (Ahmednagar: Adi K. Irani, 1948).

Duce, Ivy Oneita, How a Master Works (Walnut Creek, CA: Sufism Reoriented, 1975).

Jessawala, Eruch, That’s How It Was: Stories of Life with Meher Baba (North Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Foundation, 1995).

Kalchuri, Bhau, Feram Workingboxwala, David Fenster et al, Lord Meher (20 vols, Reiter edn 1986-2001).

Masson, Jeffrey, My Father’s Guru (London: HarperCollins, 1993).

Natu, Bal, Glimpses of the God-Man, Meher Baba (6 vols, various publishers, 1977-94).

Parks, Ward, ed., Meher Baba’s Early Messages to the West: The 1932-1935 Western Tours (North Myrtle Beach, SC: Sheriar Foundation, 2009).

Purdom, Charles B., The Perfect Master: The Life of Shri Meher Baba (London: Williams and Norgate, 1937).

———The God-Man: The life, journeys, and work of Meher Baba with an interpretation of his silence and spiritual teaching (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1964).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Meher Baba, an Iranian Liberal (Cambridge: Anthropographia, 1988).

———Investigating the Sai Baba Movement (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2005).

———Hazrat Babajan: A Pathan Sufi of Poona (New Delhi: Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 2014).

Stevens, Don E., ed., Listen Humanity (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1957).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 72

Copyright © 2017 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

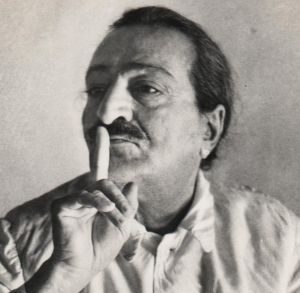

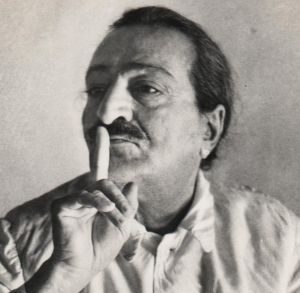

Meher Baba 1957

Meher Baba 1957