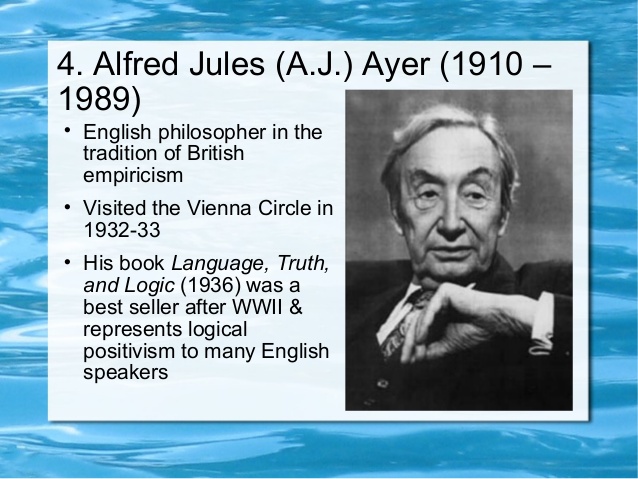

Moritz Schlick

In addition to the Vienna Circle, there was a similar gathering in Germany known as the Berlin Circle, inspired by Hans Reichenbach. However, the Vienna Circle gained more fame, assisted by the publication in 1929 of a German pamphlet often known as the Vienna Circle manifesto. The English translation of the pamphlet title is The Scientific Conception of the World: The Vienna Circle.

This document amounted to a summary of the formulations favoured, including a reliance upon empiricism or “knowledge gained by experience.” There was strong opposition to metaphysics and the doctrine of synthetic a priori truths associated with Immanuel Kant. The contention here is that a uniform scientific language should be the medium for all knowledge. The manifesto defers to the Tractatus of Wittgenstein, a book originally published in German as Logisch-philosophische Abhandlung (1921).

The contribution of Wittgenstein was here problematic. The logical positivists favoured his critique of language; ironically, some of them are said to have disliked the Tractatus, deeming that work to be metaphysical. On his own part, Wittgenstein transpired to be in reaction to logical positivism in his later career.

In 1924, Schlick contacted Wittgenstein, who eventually agreed to meet him (and Waismann) to discuss the Tractatus. However, Wittgenstein subsequently concluded that the Vienna Circle were not representing his ideas correctly (Stadler 2015:219ff). He refused to attend further meetings, although he maintained a correspondence with Schlick.

The logical analysis, in favour with Schlick and his colleagues, deemed metaphysical statements to be meaningless. Such statements were said to be irreducible to statements about experience, i.e., not empirically verifiable. This meant that many traditional philosophical problems were rejected as fallacies resulting from mistakes in logical and verbal applications. However, other “problems” were awarded a reinterpretation as empirical statements, and thus deemed worthy of scientific investigation. The Vienna Circle validated statements in accord with their logical and mathematical code of “materialist” rationalism. They insisted upon a criterion of “verifiability” to determine the relevance of meaning.

A tragedy occurred when the Nazis gained power in Germany and Austria. Science could not compete with Fascism at this juncture. The Vienna Circle dispersed, a fair number of the members emigrating to America, where they became influential in universities. Schlick chose to stay in Austria, where he was murdered in 1936 by a fanatical student at the University of Vienna (Stadler 2015:597ff). The killer later became a member of the Austrian Nazi party.

Meanwhile, Friedrich Waismann (1896-1959) had extensive conversations with Wittgenstein, who influenced him to some extent. Nevertheless, Waismann came to believe that Wittgenstein had betrayed logical positivism with a diverging argument. Waismann became a lecturer at Oxford University. He is noted for his radical paper of 1956 entitled How I See Philosophy. In this article, Waismann arrived at the conclusion that philosophy is “very unlike science in that in philosophy there are no proofs, no theorems and no questions that can be decided.”

Philosophy cannot accurately be reduced to either science or language, despite many attempts of conceptualists in those directions. A question may be resolved in ways that are elusive of association with scientific procedure and not determined by modes of language.

Rudolf Carnap

The German philosopher Rudolf Carnap (1891-1970) was especially influential amongst the logical positivists. His early book Pseudoproblems in Philosophy (1928) maintained that many traditional “philosophical problems” were meaningless, being the result of faulty language. Carnap advocated the elimination of metaphysics from philosophical discourse, an emphasis which became a characteristic of his circle. He envisaged a new democratic and rational society enlightened by scientific knowledge (Carus 2007).

Carnap met Wittgenstein in the 1920s. In his autobiography, Carnap describes his encounter with the Tractatus author at Vienna:

The impression he made on us was as if insight came to him as through a divine inspiration, so that we could not help feeling that any sober rational comment or analysis of it would be a profanation. Thus, there was a striking difference between Wittgenstein’s attitude to philosophical problems and that of Schlick and myself….Wittgenstein, on the other hand, tolerated no critical examination by others, once the insight had been gained by an act of inspiration. (David Auerbach, Carnap Meets Wittgenstein)

In The Logical Syntax of Language (1934), Carnap reformulated the concept of logical syntax proposed in the Tractatus. Carnap stressed philosophy as “the logic of the sciences,” which some critics say is too narrow a definition. His subsequent book Philosophy and Logical Syntax (1935) again rejected metaphysics, favouring the concept of verifiability in strict positivist idiom (see further Schilpp 1963).

Carnap emigrated to America, for many years being a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Chicago. “Since ordinary language is ambiguous, Carnap asserted the necessity of studying philosophical issues in artificial languages, which are governed by the rules of logic and mathematics” (see Mauro Murzi, “Rudolf Carnap,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

After Wittgenstein, the second complication for logical positivism was the contribution of Karl Popper, who became famous as a critic of the positivists. His early work Logik der Forschung (1934) disputed the verifiability criterion, urging that this should be replaced by a criterion of falsifiability to compensate for excesses. This conflict has been much discussed; strong arguments are lodged against Popper’s tendency to diminish the importance of induction. However, Popper was nevertheless concerned to separate scientific from pseudoscientific statements, without insisting that metaphysical statements are necessarily meaningless.

In his autobiography, Popper says that he heard about the Vienna Circle in 1926 or 1927. He read the books of Carnap as these were published. “They [the Circle] were trying to find a criterion which made metaphysics meaningless nonsense, sheer gibberish, and any such criterion was bound to lead to trouble, since metaphysical ideas are often the forerunners of scientific ones” (Popper 1992:80).

Popper preferred the guideline that “scientific theories always remain hypotheses or conjectures” (ibid:81). He furnished an illustration via the Einsteinian revolution in physics, which “had shown that not even the most successfully tested theory, such as Newton’s, should be regarded as more than a hypothesis, an approximation to the truth” (ibid).

In contrast, Carnap became noted for asserting that metaphysicists are like musicians with no musical ability. Metaphysics was here relegated to the status of an art, not a science, and one amounting to poetry.

Is the relegated art in all cases the same poetry? Are dogmatic theologians really demonstrating the same artistry as metaphysical philosophers like Plotinus and Spinoza, or a linguistic “contemplative” such as the aphoristic Wittgenstein? Certainly, the Tractatus was at the root of logical positivism; this ambiguous work can be interpreted as an opposing factor to the format upon which it was grafted.

At the opposite extreme are those who deny all relevance to logical positivism, a significant minority movement of scientific intellectuals, attempting to negotiate Kantian and Hegelian arguments (positivists did not reject all the Kantian repertory by any means). Logical positivism was the ideological counter to Fascism, losing out to “ordinary language,” afterwards surviving in the intellectual language of analytical philosophy.

Bibliography

Ayer, Alfred J., Logical Positivism (Glencoe, Illinois: Free Press, 1959).

Carnap, Rudolf, The Logical Syntax of Language, trans. R. Smeaton (London: Kegan Paul, Trench Trubner, 1937).

Carus, A. W., Carnap and Twentieth Century Thought: Explication as Enlightenment (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

McGuinness, Brian, ed. and trans., Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle: Conversations Recorded by Friedrich Waismann (Oxford: Blackwell, 1979).

Popper, Karl, Logik der Forschung (Vienna, 1935), trans. as The Logic of Scientific Discovery (London: Hutchinson, 1959).

——–Unended Quest: An Intellectual Autobiography (1974; new edn, London: Routledge, 1992).

Schilpp, Paul A., ed., The Philosophy of Rudolf Carnap (La Salle, Illinois: Open Court, 1963).

Stadler, Friedrich, The Vienna Circle: Studies in the Origins, Development, and Influence of Logical Empiricism (2001; new edn, Vienna: Springer, 2015).

Waissmann, Friedrich, Philosophical Papers, ed., B. McGuinness (Vienna: Springer, 1977).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness (London: Routledge, 1961).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

January 16th 2010 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 9

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.

J. L. Austin

J. L. Austin