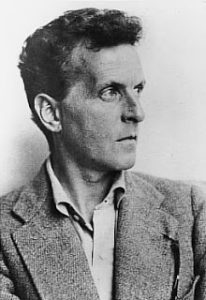

Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1930

One of the most celebrated modern philosophers is Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951). He early wrote the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), believing that he had solved all the outstanding problems of philosophy in this compact work. The Tractatus was much favoured by the Vienna Circle, a group of scientists and philosophers who pioneered logical positivism, and who interpreted Wittgenstein in that light. The Vienna Circle emphasised language, in terms of a presiding insistence that the only meaningful statements are those which are empirically verifiable. In other words, what you cannot prove, never state, because such a statement is worthless. Metaphysics, for instance, is out of bounds.

The Vienna Circle survived their diaspora in the face of the Nazi regime. Logical positivism lived on in America and Britain, later becoming influential. This contingent made a relevant critique of Fascist propaganda, a form of political rhetoric saturating Germany and other countries during the 1930s and early 1940s.

Wittgenstein was born in Austria, coming from a wealthy industrialist family, his father being a steel magnate. However, he became a British citizen, one strongly linked to Cambridge University. When I was a young man (and a resident of Cambridge), the dons would discuss “what Wittgenstein really meant.” There were permutations of this during my temporary employment under Professor J. P. Stern, who enthused about Kant, Wittgenstein, and Nietzsche in our conversations dating to 1973. These talks occurred in his book-lined study, overlooking a panoramic garden in a select area of Cambridge.

Professor Stern (who taught German at London University) was an expert on Nietzsche. I found great difficulty in conceding the importance of Nietzsche. I also found the Tractatus a disconcerting work, though in a different way to Thus Spake Zarathustra. Professor Stern pressed upon me the Tractatus when he grasped that I had an interest in philosophy. He expected me to enthuse over the treatise, as many undergraduates did at that time. I was a citizen exception to the intellectual fashion. I never did find the Tractatus inspiring; to me, the format was obscurantist. That book is generally considered significant in the history of philosophy.

Stern was one of the more liberal academics in Cambridge. Even he could not understand my citizen viewpoint on some matters. He assumed that one had to elevate Wittgenstein and Kant for the purpose of gaining intellectual clarity. I merely regarded these thinkers as interesting, not as figureheads of an ultimate philosophy. In some Cambridge colleges, there was an attitude of semi-worship attaching to Wittgenstein, despite his own aversion to such trends.

Wittgenstein had early read Schopenhauer, whose worldview he apparently believed was to some extent correct. He was impressed by his predecessor’s theory of the “world as idea,” but not the “world as will.” Schopenhauer therefore needed “adjustments and clarifications” (Anscombe 1959:11ff). “Schopenhauer’s influence on Wittgenstein was considerable, but for the most part indirect and negative” (Severin Schroeder, Schopenhauer’s Influence on Wittgenstein, p. 23, online). Nevertheless, Wittgenstein assimilated Schopenhauer’s division between the noumenal and the phenomenal, himself emphasising the phenomenal world in his Tractatus (Magee 1997:310ff). Schopenhauer was acknowledging a theme of Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), who earlier defined the noumenal as the unknowable, using the terminology of Thing-in-Itself (Ding an Sich). In contrast, the Vienna Circle believed that only the phenomenal world existed, seeing support for their ideology in the Tractatus.

Wittgenstein conveyed that any metaphysical reality is beyond conceptual grasp, and therefore a factor of which nothing can be said. Only the phenomenal world can be described. Various objections have been lodged against this perspective. However, in the 1970s, the exegesis of Wittgenstein was very much in the ascendant at Cambridge. When meeting incredulity from academics (as I sometimes did), there is nothing that can usefully be said.

Wittgenstein himself demonstrated a dissatisfaction with the Tractatus at a later phase of his career. By then he knew that he had not solved all the problems of philosophy. The Tractatus had been influenced by theories of the mathematician Gottlob Frege and the author’s own tutor Bertrand Russell. Critics say that the Tractatus is ambiguous and contradictory; they even urge that Wittgenstein’s format of logic made nonsense of his own propositions. He maintained that philosophical problems arose from a failure to understand the logic of language.

Amongst the academic philosophers, Wittgenstein is the one who came closest to being a citizen philosopher. In 1912 he became an undergraduate at Cambridge, but reacted to the example of his tutor Bertrand Russell, who at this time authored The Problems of Philosophy (1912).

“ ‘How few there are who do not lose their own soul,’ remarked Wittgenstein one day. Russell felt obliged to tell Wittgenstein that he would not get his degree unless he learnt to write ‘imperfect things,’ a constraint which incurred the junior’s displeasure.” (Shepherd, Meaning in Anthropos, Cambridge 1991, p. 149)

Neglecting the degree, Wittgenstein moved back to the Continent. At this time he became a rich man, gaining the fortune of his deceased father, an industrialist tycoon. Yet he retired to Norway, building himself an isolated hut near Skjolden, his intention being to live in complete seclusion. The First World War changed his plans; he then volunteered to join the Austrian army, and fought on the Russian front. After the war, he became a schoolmaster, teaching at various remote villages in Austria. At a school in Otterthal, he gained a reputation for administering severe corporal punishment to pupils finding difficulty with mathematics, in which he was himself very competent. He subsequently became a gardener and an architect. He later expressed a discontent with scientism.

Two of his friends criticised the Tractatus. Wittgenstein is said to have abandoned his earlier views. In 1929 he returned to Cambridge, quickly acquiring a Ph.D. (on the basis of the Tractatus) after his lengthy absence of sixteen years in obscurity. He thereafter did much writing, but without publishing the result, apparently because he did not wish to be misunderstood. Dr. Wittgenstein was noted for his unconventional lectures uttered in a mood of deep concentration.

The advantages of his transition to academic status are not totally convincing. He remained a virtual alien within academic life; his aversion to appearing in the college dining room is a well known detail. Wittgenstein regarded all the talking as superficial. He frequently visited the local cinema in an effort to suspend his prolonged concentration on philosophy; he could appear quite desperate not to be distracted while watching the film (he was partial to Hollywood westerns and musicals). During the 1930s, he escaped for nearly a year to his distant hut in Norway. In 1947, he ceased to lecture at Cambridge, instead moving to Ireland, where for a time he lived alone in a hut beside the sea in Galway (for a partisan account, see Malcolm 1958; for a more detailed biography, see Monk 1990).

Some critics accuse Wittgenstein of being idiosyncratic, self-absorbed, suicidal, and homosexual. He certainly possessed a strong personality; he criticised both himself and colleagues. “His sexuality was ambiguous but he was probably gay; how actively so is still a matter of controversy” (Duncan J. Richter, “Ludwig Wittgenstein,” Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy).

After his death, many of his writings surfaced in print. The most famous of these later works became his Philosophical Investigations (1953). Wittgenstein was here committed to what is known as linguistic philosophy. He emphasised language as a tool, and introduced the concept of “language game.” A number of differing interpretations of his ambiguous output have emerged. Wittgenstein regarded philosophy as a therapeutic activity for dispelling linguistic confusions. Critics say that his treatment of philosophy as language can be considered more of a philosophical problem than a solution.

The meaning of life remains a mystery to much contemporary philosophical language. Wittgenstein failed to describe his own notable striving for experiential equipoise. The new language philosophy did not describe, for instance, the hut in Norway or his recurring thought of entering a monastery. His frustration with artificial surface discourse is evident. Wittgenstein is unusual in this respect.

The intrinsic struggle to penetrate “philosophical problems” is a feature of mind rather than language. This factor appears to be confirmed by what Rudolf Carnap described as “an act of inspiration,” referring to the manner in which Wittgenstein communicated:

When he started to formulate his view on some specific problem, we often felt the internal struggle that occurred in him at that very moment, a struggle by which he tried to penetrate from darkness to light under an intensive and powerful strain, which was even visible on his most expressive face. (Carnap Meets Wittgenstein)

Bibliography

Anscombe, G. E. M., An Introduction to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus (London: Hutchinson, 1959).

Frongia, Guido, and Brian McGuinness, Wittgenstein: A Bibliographical Guide (Oxford: Blackwell, 1990).

Klagge, James C., ed., Wittgenstein: Biography and Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Magee, Bryan, The Philosophy of Schopenhauer (1983; revised edn, Oxford University Press, 1997).

Malcolm, Norman, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir (Oxford University Press, 1958).

McGuinness, Brian, Wittgenstein: A Life, The Young Ludwig, 1889-1921 (University of California Press, 1988).

Monk, Ray, Ludwig Wittgenstein: The Duty of Genius (London: Cape, 1990).

Redpath, Theodore, Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Student’s Memoir (London: Duckworth, 1990).

Sluga, Hans, and David G. Stern, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein (second edn, Cambridge University Press, 2018).

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, trans. D. F. Pears and B. F. McGuinness (London: Routledge, 1961).

——–Philosophical Investigations, trans. G. E. M. Anscombe (Oxford: Blackwell, 1963).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

November 17th 2009 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 2

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.