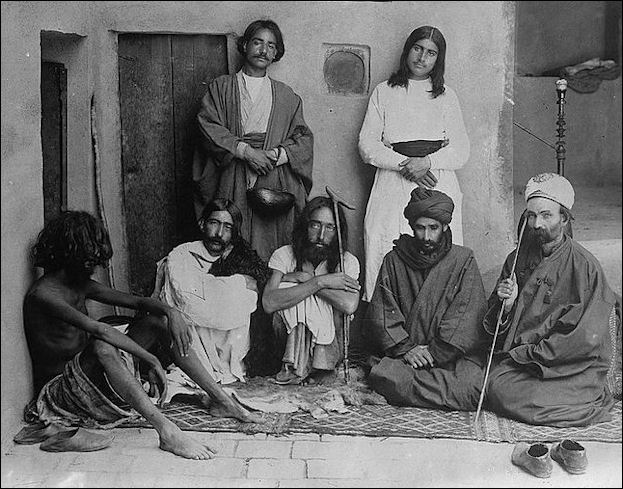

Persian Dervishes

This site has been commenting on diverse angles of analytical academic philosophy and the unofficial conceptualism of citizen philosophy. The Cambridge and Oxford traditions were profiled (entries 2-8), with some Continental extensions in logical positivism.

My own angle has been broached, in the form known as interdisciplinary anthropography, or philosophy of culture. The distinction between different forms of independent philosophy requires recognition, contrasting with the frequent enclosed preferences for Nietzsche.

Factors involved in controversy about the influential integral theory of Ken Wilber are relevant. Reservations are expressed about contemporary mindset in the commercial guise of Mind, Body, Spirit, a phenomenon contributing to the decline in literature. Manifestations of contemporary pseudomysticism are repudiated, including the symptoms of “cult” thinking that have become notorious.

The citizen way forward must be far more disciplined than panaceas offered by the commercial mindset of pop-mysticism. For instance, in referring to the history of religion, due critical ballast should be provided by recourse to specialist sources.

The history of philosophy is not popular today. No apology need be offered for approaching that subject in a more rigorous sense than is evidenced by new age dismissals, often promoting so-called “holistic” conveniences omitting analysis in favour of fantasy.

With regard to the history of religion, I have proffered the online article Early Sufism in Iran and Central Asia (2010). The subject here is distanced from the field of conventional philosophy, but does not comprise an insurmountable problem for the independent thinker. One may emphasise the relevance of investigating an international phenomenon extending from the Near East to Central Asia (and India in later centuries). Analysis of the topographical and conceptual features of the early Islamic cultural landscape is a challenge. There are varied explanations for Iranian mystical religion (now known as Sufism) amongst Islamicist scholars. The “Persian dervishes” are a subject evidencing a wide variety of temperaments and teachings over many centuries.

Sheriar Mundegar Irani

An unusual instance of the “Persian dervish” was Sheriar Mundegar Irani (1853-1932), a Zoroastrian of Yazd who became a mendicant at an early age. His distressed community on the Yazd plain was afflicted by Islamic prejudice. Although Sheriar is often described as a dervish, he remained a Zoroastrian. He eventually emigrated to India, where after further wanderings, he settled at Poona. See further Shepherd, From Oppression to Freedom; A Study of the Kaivani Gnostics (1988).

Shirdi Sai Baba

The equivalent “dervish” population in India included the diverse categories of faqir, a word that became largely meaningless in British colonial usage. The term is frequently associated with snake charmers and exhibitionists lying on a bed of nails. I have contributed studies of two faqir entities in Indian environments. Hazrat Babajan (d.1931) was a distinctive Pathan female mystic of Maharashtra (Shepherd, Hazrat Babajan: A Pathan Sufi of Poona, 2014). Sai Baba of Shirdi (d.1918) is to some extent obscured by hagiology, but sufficient detail exists to profile a liberal Sufi faqir who notably avoided any religious dogmatism. This tendency accommodated a predominantly Hindu following, despite some Muslim characteristics in evidence (Shepherd, Sai Baba of Shirdi: A Biographical Investigation, 2015; Shepherd, Sai Baba: Faqir of Shirdi, 2017).

With regard to the history of philosophy, one should continue to be broad-ranging rather than unduly selective. Thinkers like Bertrand Russell and Kant do not exhaust the scope for potential insights. Plato, al-Farabi, Ibn Rushd, Suhrawardi, and many others of more distant centuries can still be honoured, doubtless with some surprises in store around committed corners of the mentation effort.

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

March 13th 2010, modified December 2018

ENTRY no. 15

Copyright © 2018 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.