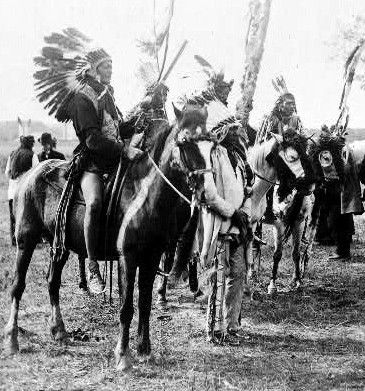

Kicks Iron of Standing Rock Sioux, with headdress of golden eagle feathers c. 1905. Photograph by Frank Bennett Fiske (1883-1952). Courtesy CNN

Over many years, the Sioux Indians were afflicted by broken promises and stolen land. They lost to the invasion of white settlers and greed for gold. The white media vindictively depicted them in terms of primitive poverty and alcoholism. One of the legends depicted “savage” Indians scalping “civilised” whites, a proclaimed reason for killing Indians.

Colonialist Society of Scalpers

The practice of scalping has been diversely argued in terms of antecedents. Archaeology indicates that scalping was known to Native Americans in Pre-Columbian times, later intensifying when encouraged by European colonists and the introduction of metal knives. Among the Plains Indians, scalps were taken from enemies killed in battle (Miller 1994).

In Europe, the practice goes back to Stone Age Denmark and Sweden several thousand years ago. In the fifth century BC, the Scythians were reported in this context by Herodotus. In the Black Sea zone, Scythians scalped their enemies defeated in battle. Scalping was a vogue in eleventh century England, where the Anglo-Saxon Harold Godwin, the first Earl of Wessex, used enemy scalps from battle to prove deaths (Chavers 2018). Godwin was made an Earl by the Danish king Cnut (Canute).

When Europeans invaded the Americas, disease and genocide became the fate of Natives. In 1637, the English Puritans murdered about 400 (or 600) Pequot Indians at Mystic, burning their village and killing survivors. Many Pequots were enslaved, some being sent to Bermuda and the West Indies. Others were forced to work as slaves to the English in their homes at Connecticut. Money and status were conferred upon colonists who secured heads and scalps of fugitive Pequots.

Over fifty years later, a Massachussetts law of 1695 gave colonists permission to kill Indians at will. These Puritans of New England were Calvinists who downgraded women, slaves, servants, and Indians. They believed that most of humanity were predestined to damnation. This fantasy assisted their oppression of Ireland and North America, also the spread of slavery, involving both Native Americans and Africans. Runaway Indian slaves were branded. The Puritans elevated a powerful class of merchants, establishing the basis of American capitalism, meaning prosperity for a few at the expense of many.

There was a big difference between scalping the dead on a battlefield and a manhunt for the purpose of obtaining payment for scalps. This white enterprise achieved huge proportions. In 1647, the wealthy Dutch Governor of Manhattan gave orders for a bounty in pursuit of Indian scalps, only 21 years after the Puritans had landed. The French competed with the English in the vogue for scalping. Bounties for Indian scalps became a rule in at least 23 colonial American states (also Canada, another horror zone). That means men, women, and children being hunted down for scalps in a concerted programme of genocide. White settlers could be paid for the scalp of an Indian child. The bloodstained colonial Euro-Americans killed and scalped large numbers of Natives in Virginia, Kentucky, Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Colorado, Arizona, California, New Mexico, and other states. White settlers killed Indians by the thousands in almost every state (Chavers 2021). Beliefs in Indian savagery discrepantly justified white Americans in their extremist violence against Indians (Brundage 2018).

Tribal extinction could easily occur. At Pennsylvania in 1763, the Paxton Boys (a vigilante group) killed, scalped, and savagely dismembered twenty innocent and defenceless Indians (men, women, and children). These victims were the last living members of the Christianised Conestoga tribe. The Paxton Boys were Scots-Irish frontiersmen, also Presbyterians who believed they were a predestined elect. Their attitude contrasted with the urban pacifism of the Quakers at Philadelphia. Quakers rejected the Calvinist belief in predestination; they received oppressive treatment from Puritans in New England.

British and American Indian Raids, etching with watercolour by William Charles (1776-1820), published at Philadelphia 1812. Shows the British practice of offering bounties for white American scalps. Courtesy Library of Congress/Science Photo Library

The French and Indian War (1754-63) saw much scalping by the French, English, and Indian combatants. This was a struggle between British Empire colonies and the French colonials, each side being supported by Indians. In the American Revolutionary War (1775-83), both Patriots and Tories scalped for the purpose of terrorising foes, with each side claiming that their foe embodied Indian savagery. “Englishmen scalped Englishmen in the name of liberty” (Brown 2016). Patriots were keen to scalp other Englishmen. Further, in relation to violent attacks, “Patriots widely approved and often celebrated such atrocities when committed against Indians” (ibid). The Iroquois tribes, allied with the British Tories, lost the fight and ended up starving, their crops burned, their homes destroyed.

In 1782, militiamen of Pennsylvania bludgeoned to death and scalped at least ninety Christian Delaware Indians of Ohio, the majority of whom were women and children. In 1851, the Californian governor Peter Burnett declared that “a war of extermination will continue to be waged… until the Indian race becomes extinct” (on massacres, see further Madley 2015; Madley 2016).

A massacre of helpless Yuki Natives followed less than two years later, the first of many pogroms in the California “paradise” zone that white settlers were eager to regard as their exclusive property. The white murderers raped, stole, and sold innumerable Native women and children. The invaders killed and crippled naked children who had no chance against their venom. The murderers and torturers were both civilians and soldiers.

When Spanish colonists arrived in 1769, Californian Indians numbered over 300,000. Between 1846 and 1873, the Native American population in California dropped from 150,000 to 30,000. The reasons were white American greed for Californian goldfields, disease, abduction, massacres, and mass death from starvation on reservations. Much of the genocide was organised, and paid for, by civil and federal government. Vigilantes and Army soldiers massacred Natives, while civilian lawmakers deprived them of legal power and rights. The US Senate rejected a series of treaties made by the government with Californian Indians, “a deceitful crime of vast proportions” (Madley 2016:168).

The genocide was not officially recognised in California until 2019. The wealthiest American state, like many other states, flourished on a Native death toll whitewashed by colonialist propaganda. The conventional history of California is aberrant contraction. “We Californians are the beneficiaries of genocide” (Lindsay 2012:x). The same scholar states: “The rhetoric of freedom, liberty and democracy has been put to terrible use in the past” (ibid).

The Spanish-Mexican city of Los Angeles became a US zone in 1850. The Native American population here were drastically reduced, from a few thousand to only 219, during the period c.1850-70. A system of alcohol-induced enforced labour perpetuated the plight of Christianised Indians in this city, where they were denied citizen status and sold in auctions. The Anglos (English-speaking whites) of Southern California became infamous for their treatment of Indians, whom they hunted for sport.

In 1856, the racist mood was expressed by a governor of Washington Territory, Isaac Stevens, a military officer who declared: “War shall be prosecuted until the last hostile Indian is exterminated” (Madley 2015). Some colonialists viewed all Natives as hostiles. In 1862, General John Pope, of the US Army, wrote to a subordinate officer: “It is my purpose utterly to exterminate the Sioux” (ibid).

Nomadic Horsemen

The Sioux nation were hunters and warriors, their society dating back about 3,000 years or more. During the seventeenth century, they were pushed westward by other tribes in the Great Lakes zone. They are identified in regional terms. The Lakota (Sioux of the West) did not become nomadic horsemen of the Plains until 1750-75 (Gibbon 2003:4-5). The Dakota (Sioux of the East) were at first closely involved in the French fur trade, but most of them likewise became nomadic hunters. The horse (sunkawakan) was a substantial asset.

Two Sioux on horseback, 1899. Courtesy Heyn

Two Sioux on horseback, 1899. Courtesy Heyn

The Lakotas (Teton Sioux) were the iconic buffalo hunters on the prairies. The herds provided them with food and clothing. The Lakotas lived in large tents (tepees) made of buffalo hide, erected by the women. They prospered, eventually outnumbering all other Sioux communities combined. The Lakotas comprised the last barrier to white domination of the Plains.

By the 1830s, the nomadic Sioux and Cheyenne had subjugated most of the sedentary tribes on the Plains, and were at war with the resisting Pawnees. For decades, the Pawnee tribes, living in Nebraska and northern Kansas, had developed a military code. During the 1840s, the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho created an alliance against the Pawnee. Fighting could be fierce, causing many deaths; scalps of women were taken (Van de Logt 2010:33-36). This warfare intensified in the 1860s, when the buffalo herds were reduced.

Two types of Indian raid occurred. A common tactic was to steal horses in a small scale attack careful to avoid detection. Larger expeditions were for the purpose of killing the enemy and taking scalps. Most of the Plains tribes took scalps, fetishes associated with the life force of those defeated. In addition, the valorous act of “counting coup” was achieved by touching or striking the enemy with the hand or a coup stick. In this warrior society, daring coups conferred prestige.

The Pawnees developed a tactic of conciliating with the US Army. They made a treaty with the whites in 1833, promising not to fight. They were under pressure to adopt an agrarian lifestyle, Presbyterian missionaries being an agitation. The Sioux warriors remained independent, launching frequent attacks against Pawnee allies of the Army. Pawnees acted as scouts for the US Army during the Indian wars on the Plains.

Sioux Horsemen

Sioux Horsemen

Until the 1840s, the situation on the Plains was generally peacable between Indians and whites. In 1842, the first pioneer wagon train travelled across Sioux land on what became known as the Oregon Trail. This development caused the buffalo herds to move away and upset the hunting routine of the Sioux (Lazarus 1999:13). Friction with the US Army occurred in 1854.

In August 1855, Colonel William Harney led a platoon of 1,300 soldiers to attack Sioux at Ash Hollow camp. The Natives tried to surrender, an action which Harney ignored, his mission being “to strike terror into the Sioux” (ibid:23). There were only a few hundred Sioux at the camp, many of them women and children. The encounter is described as a massacre, with 86 Natives killed (ibid). The survivors were taken in chains to Fort Laramie. “Indian hating spread like a prairie fire” (ibid:29).

Alcoholism was only one of numerous illnesses that the [white] traders brought to the Plains. Cholera, smallpox, and venereal disease infected the defenceless Indians. (Lazarus 1999:12)

Bear River Massacre

To the west, the Sioux were also at war with the Shoshone. Some historians view the US Army massacre of Shoshone Indians, at Bear River in 1863, as the worst event of this kind. At least 250 (or 490) were killed, including many women and children, at a winter camp in Utah. The Californian Volunteer soldiers were the murdering culprits, losing only 23 of their number (Madsen 1985). The Shoshone chief Bear Hunter was tortured by soldiers who captured him. Because the victim showed no fear of pain, the relentless captors heated a rifle bayonet and “ran it through his head from ear to ear.” This report came from the Shoshone informant Mae Parry (d.2007), who described the event as a massacre, discounting the more sanitised description of “battle” preferred by the military.

Whitestone Hill Massacre

The Lakotas became a strong component of the Standing Rock Reservation. Also represented were the Yanktonai, part of the Nakota or “Middle Sioux.” In 1863, General Alfred Sully encountered a large hunting camp or village, including many Yanktonai Sioux, at Whitestone Hill in North Dakota. These people were not posing any threats, but merely preparing food for winter. Over 600 soldiers killed at least 300 Sioux, many of them women and children. Only 20 soldiers were killed (and 38 wounded), some by their own gunfire. The Natives fled, while others were taken prisoner. The village property and winter food stores were relentlessly destroyed by the invaders (Shields 1995:34). Despite their crimes, Sully’s men were officially congratulated for their conduct.

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard

LaDonna Brave Bull Allard

The Sioux account contradicts a cosmetic US army version of the Whitestone episode. According to Standing Rock Sioux historian, LaDonna Brave Bull Allard (1956-2021), the soldiers accomplished a massacre. They killed the dogs and babies (the mothers had tied the babies to dogs to assist escape). They killed horses (children were tied to them). The attackers killed the wounded Sioux. They made a huge fire and burned everything the victims owned. Victims fled for days to escape the carnage, with soldiers chasing them. Prisoners were taken to oppressive POW camps at Crow Creek, where they remained for several years (Standing Rock Sioux Historian Interview, 2016, online). According to another report, the soldiers attacked during a buffalo hunt; they gunned down more than 400 Lakotas and Dakotas in a manhunt up and down the river (Estes 2019).

The Sully belligerents had apparently misidentified the Yanktonai as Santee Dakota Sioux who caused an uprising in Minnesota the previous year (a number of Santee and Lakota were also present at Whitestone). Santee discontent was aggravated by a delay in government annuity payments, causing hunger to a disadvantaged population. Santee warriors reacted to their neglect by raiding settlements, killing hundreds of white farmers in the Minnesota War of 1862. The subsequent “Dakota War” of 1863-65 involves disputed details (Clodfelter 1998 describes the friction as an “inevitable conflict between the progressive and the primitive”; such assumptions of the author are considered misleading by other analysts).

Santee Rebellion

By 1862, the Santee zone in Minnesota had been “reduced to a sliver,” only 10 miles wide and 150 miles long, formerly a vast territory since appropriated by whites (Clodfelter 1998:37). When US government annuity payments were delayed and crops failed, Santees were refused credit by white Indian agents (like Major Galbraith) and traders like Myrick, who was in charge of food distribution to Sioux. When the Santee complained of starvation, Myrick said contemptuously: “Let them eat grass.” The superiority complex of many whites was tangible. The sun shone out of their heads. There was much Santee resentment at the abuse of Indian women by white men.

In August 1862, a contingent of 400 Santee attacked local whites. The detested Myrick was amongst the first to die, with grass being stuffed into his mouth, a retaliation for his edged jibe. Of course, the rebels soon lost to greater numbers, 38 of them being condemned to hanging. One of those mistakenly sentenced to death had saved a white woman from harm during her captivity. The grateful woman pleaded in vain for the life of Chaska. His name was confused by the authorities with another rebel who had killed a pregnant woman (Clodfelter 1998:58). Justice can be anomalous.

The government response to complaints of treaty violation was to build more forts for the purpose of protecting white settlers and railway crews. US soldiers are reported to have burnt tons of Sioux food – dried buffalo meat and dried berries – along with tepees and domestic utensils. Thousands of Santee fled to Canada. Minnesota expelled all Sioux after the Dakota War; the authorities sold all Sioux land in the state. This acutely unequal arrangement was singularly convenient for mushrooming white settlements.

Sand Creek Massacre

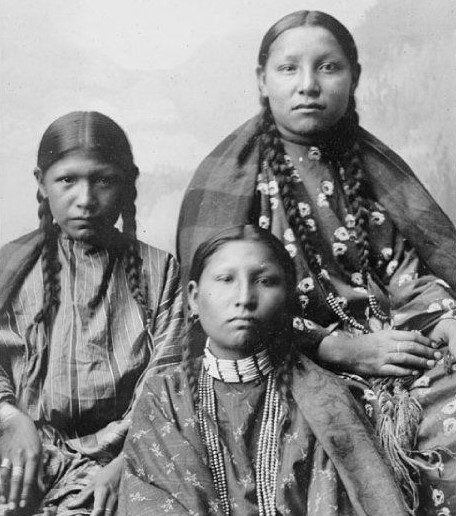

Southern Cheyenne Girls, 1895

Southern Cheyenne Girls, 1895

US Army savagery occurred at the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Colonel John Chivington (1821-94), with his Colorado cavalry militia, destroyed a village of peaceful Cheyenne and Arapaho in Colorado. Chivington was a zealous Methodist minister from Denver. He attacked “with a force of 600 Indian haters rustled up off the streets of Denver; they spent the better part of the day tracking down and beating to death women and children who had managed to escape the initial onslaught, then mutilated the corpses – beyond recognition” (Lazarus 1999:29). The atrocities included “pregnant women sliced open” (ibid).

Chivington’s bloodthirsty men killed at least 148 victims, two thirds of whom were women and children. Only nine of the attackers were killed. Only some of the victims were armed. After conducting a despicably violent manhunt, the militia killed the wounded and set fire to the village. A military testimony complained of “children shot at their mother’s breasts” (Jackson 1881:344), while Chivington was “all the time inciting his troops to these diabolical outrages” (ibid).

Prior to the massacre, Chivington urged: “Damn any man who sympathises with Indians… I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honourable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians… Kill and scalp all, big and little” (Chavers 2018). Onward merciless Christian soldiers. The colonialist scalpers are commemorated in a testimony of 1865 by John Smith, who reports of Sand Creek:

I saw the bodies of those lying there cut all to pieces, worse mutilated than any I ever saw before; the women cut all to pieces…. With knives; scalped; their brains knocked out; children two or three months old.

Another well known testimony of Robert Bent (dating to 1879) informs: “I saw one squaw cut open, with an unborn child lying by her side” (Jackson 1881:344-5). Bent saw another squaw, still living, with a broken leg; her helpless plight was further damaged by a pitiless soldier who broke both of her arms with a sabre (ibid).

Some of Chivington’s men testified against him. A strong public outrage occurred in the East against the brutality at Sand Creek. The “Friends of the Indians” emerged in Eastern cities far removed from the grim massacre. Whereas the local white population justified the violence. Cheyenne scalps were paraded in Denver, along with other grisly momentoes of massacre. Chivington resigned from the Army, being described in the press as a “clerical hypocrite.”

Congress Colonialism

The formidable Oglala Lakota chief Red Cloud (1822-1909) achieved a victory over the US Army in 1866, allying with the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Sioux were masters of ambush and surprise attack. Along with over twenty other tribal leaders, Red Cloud subsequently signed a treaty in 1868 at Fort Laramie. This arrangement, creating the Great Sioux Reservation, prohibited white settlement in the Black Hills.

Native American Delegation to Washington, 1875, led by Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud (bottom row, second left)

Native American Delegation to Washington, 1875, led by Oglala Sioux chief Red Cloud (bottom row, second left)

In contrast, Sitting Bull (1831-90) distrusted and opposed treaties. The resistant attitude of this Hunkpapa Lakota chief proved justified. Influenced by gold greed, the US government later reneged on the 1868 treaty, demanding that the Sioux transfer to new reservation boundaries by January 1876. The alternative was to be considered an enemy of the US. Sitting Bull refused to obey, being expected to move his village over 200 miles in the bitter cold weather.

Before and after completion of the polluting railroad in 1869, herds of buffalo were slaughtered by white opportunists for hides that were sent East to the cities. Some 10 to 15 million buffalo were eliminated in less than twenty years. The herds were crucial to Sioux survival. The buffalo nevertheless disappeared, as a consequence of white greed instigated by railway interests and white settlers. Buffalo herds impeded the railway.

Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer is notorious for his attack (in 1868) on the peaceful Cheyenne at Washita River, where women and children were amongst the dead. Custer subsequently announced that he had found gold in the Black Hills, causing a gold rush violating the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868.

Lakota chief Sitting Bull circa 1883

Lakota chief Sitting Bull circa 1883

The Black Hills Gold Rush, of the mid-1870s, changed the outlook of Congress and encouraged extensive anti-Native hostility amongst greedy white settlers. The government ignored the treaty of 1868 and began to remove Native tribes from their land by force. The consequent Great Sioux Wars culminated at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Here the Lakota Sioux, along with Cheyenne allies, were led by Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. They defeated the Seventh Cavalry led by an invading Lt. Col. Custer. The “Last Stand” of Custer became a pervasively romantic white legend lacking sympathy for the Sioux and Cheyenne.

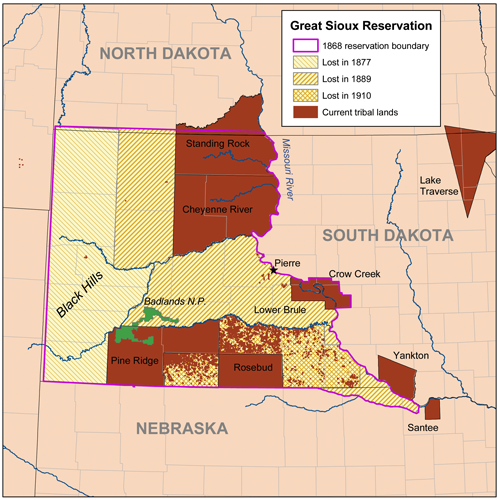

In 1877, Sitting Bull led his people to safety in Canada. He afterwards surrendered to the US Army in 1881, being granted amnesty. Both the Lakota and Dakota Sioux were relegated to a reservation, which became the further prey of scheming colonialists. To encourage white settlement, Congress passed the “Sioux Agreement.” This imposition broke up the Great Sioux Reservation into five separate camps, including Standing Rock, Pine Ridge, and Rosebud. Sitting Bull died at Standing Rock in violent circumstances associated with white oppression.

Chief Bone Necklace, an Oglala Lakota Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation, 1899.

Chief Bone Necklace, an Oglala Lakota Sioux from the Pine Ridge Reservation, 1899.

By the 1920s, Sioux reservations had lost hundreds of thousands of acres. Conditions at the Standing Rock Reservation were lamentable. Many of the inmates suffered disease and illness on meagre government rations. Their clothing was not adequate protection against cold winters. The US Congress applied pressure upon the Sioux to relinquish their traditional way of life. Many Sioux lands were opened, by the treacherous US government, to public purchase for ranching and homesteading.

During the period 1778-1871, the United States signed over 360 treaties with various Native American tribes in North America. After the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, government soldiers flooded the region. The Lakota Sioux chief Crazy Horse was bayoneted after resisting confinement in a guardhouse at Fort Robinson. By then, Colonialist Congress had ceased the practice of making treaties with Native American tribes. In 1871, an official declaration stated: “Henceforth, no Indian nation or tribe… shall be acknowledged or recognised as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the US may contract by treaty” (Sarah Pruitt, Broken Treaties, 2020). The colonialist monster could now break agreements even more easily and ruthlessly.

In 1877, the Black Hills were seized from the Sioux. This government crime was a direct violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which promised that white settlers would be prevented from encroaching upon the designated zone. The Black Hills Gold Rush, commencing in 1874, was a scenario of unrestrained greed, facilitated by Custer, who led an expedition searching for gold in Sioux territory.

A century later, in 1980, the US Supreme Court pronounced a negative judgment on the infamous seizure of the Black Hills by the US government. The Court declared: “A more ripe and rank case of dishonourable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history” (Shields 1995:40). The Supreme Court awarded 106 million dollars compensation, a gesture rejected by the Sioux on grounds of principle. Return of the land is desired, not payment.

Wounded Knee Massacre

Theresa Yellow Lodge, Standing Rock Sioux, c. 1905. Photograph by Frank Bennett Fiske

Theresa Yellow Lodge, Standing Rock Sioux, c. 1905. Photograph by Frank Bennett Fiske

The brutal US colonial soldiers could too easily be awarded medals of honour in very questionable situations. In 1890, twenty of those medals were awarded to soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry when they massacred hundreds of Lakotas who had surrendered. The victims were taken to a camp at Wounded Knee Creek, where they were surrounded by 470 soldiers with artillery. Estimates of the death toll vary from less than 200 to over 400. There is agreement that most of the dead were women and children. Babies were found with five bullet holes in their helpless bodies. The crime was generally forgotten and ignored for many years.

Death at Colonialist Punishment Schools

Hostile Christian boarding schools were intended to “kill the Indian to save the man” (to use a phrase now well known). During the nineteenth century and much later, children were taken away from families and forbidden to speak their native language. Their religion was outlawed by the complacent white oppressor.

The racist schools operated for many decades until 1969 (and later in Canada). Tens of thousands of Native children were forced into these injurious camps run by the US government and religious institutions. This situation is now described in terms of a genocidal process of “dispossession and theft of Indigenous people’s lands and resources” (Nick Estes, Boarding Schools Were Part of Horrific Genocidal Process, 2022). Many of the victims died in those atrocious institutions of “democratic America.” One estimate is 40,000 deaths. Over fifty cemeteries have been located.

The victimised children were forced into unpaid manual labour, and subjected to physical and sexual abuse. Too many of them were murdered. Daily beatings and tortures were on the agenda as far north as Alaska. American (and Canadian) colonialism was very ugly, effectively trying to write the Natives out of history books. The afflicting schools are compared to POW camps.

Not until 1985 did the Sioux, and other Native Americans, gain the right to raise their own family, free from the interference of Christian oppressors who abducted Indigenous children into the “superior” lifestyle that is killing the planet. This form of crime was also widespread in Canada and Australia. The American version enforced sterilisation of women.

The Pick-Sloan Affliction

Chief Black Chicken of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, with peace pipe, early 20th century portrait postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons, London

Chief Black Chicken of the Yankton Dakota Sioux, with peace pipe, early 20th century portrait postcard by Raphael Tuck & Sons, London

A notorious dam project was commenced in 1948 by the Army Corps of Engineers, whose construction agenda continued until 1966. The project creators of the Pick-Sloan Plan were Lewis A. Pick, an official of Army Corps, and William G. Sloan, of the US Bureau of Reclamation. More than 200,000 acres of prime agricultural land belonging to Sioux tribes were flooded. Sioux towns were submerged under Lake Oahe in South Dakota, a tragedy for which the victims are still seeking compensation. About 25 percent of the population, at Standing Rock Reservation, had to relocate outside the flood zone (Shields 1995:39). The Oahe Dam destroyed more Native land than any other public project in America, flooding 90 percent of the timber and fertile bottomland of Standing Rock and Cheyenne River Nations.

The Oahe Dam was one of five dams conceived by the Pick-Sloan Plan for the Missouri River. This project was intended to reduce flooding and to improve irrigation. Tribal lands were callously selected for damming to avoid building near white communities. Natives were considered easier to relocate than white urban residents. This activity caused havoc on five Sioux Reservations, meaning Standing Rock, Cheyenne River, Crow Creek, Lower Brule, and Yankton. The US government approved the Pick-Sloan Plan before this was presented to the Sioux. More than a third of the Sioux population was forcefully dislocated by this loaded pro-white scheme (Lawson 1982; Lawson 2009). The Yankton Sioux were amongst the victims.

Sioux land was designated as a reservoir (Lake Oahe) between two dams. The government moved the Sioux out of their own homes into low-income housing which they could not own. The dispossessed lost substantially. Army Corps flooded their lands, moving them to a barren clay soil locality where they could no longer grow gardens or plant trees. The US government and Army Corps took away their infrastructure of businesses, stores, and restaurants (Allard 2016, online). This racist strategy merits the strongest condemnation.

The US government is described as violating all treaties by the relocation of Sioux at this period, selling off their lands and resources to private industry and white settlers (Este 2019).

Protest at Standing Rock

1868 Great Sioux Reservation and the current Reservations. Courtesy Wikipedia

Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) were a multi-billion dollar natural gas enterprise based in Texas. This business launched the 3.7 billion dollar project of Dakota Access Pipeline, running across different states, the route being planned by Army Corps. This project caused alarm to Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota. The pipeline was made at the cheapest cost possible, with a danger of oil spills threatening the Missouri River. That pipeline was only 500 feet from the Reservation boundary. The attitude of ETP was that they did not have to consult with the Sioux, whose existence they effectively ignored.

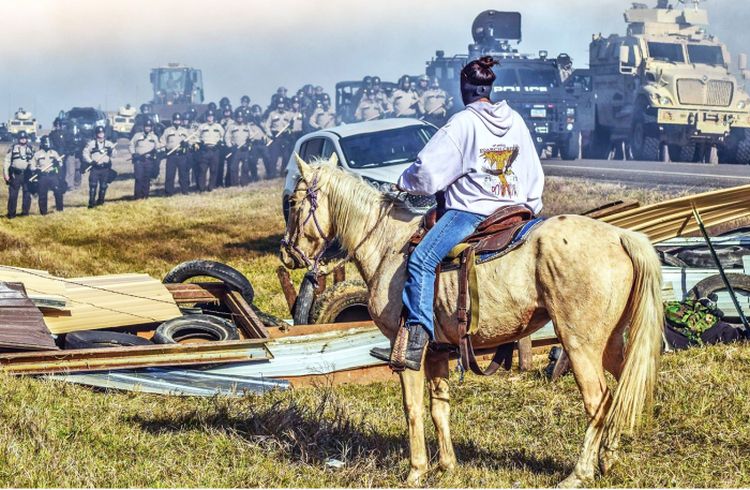

A protest by Native Water Protectors began in April 2016 at North Dakota. Three protest camps started near Standing Rock Reservation, including the large Oceti Sakowin camp accommodating thousands of people. This region was now described as ancestral Sioux land, stolen in violation of treaty. A coalition of over 200 nationwide tribes emerged. This became the largest gathering of Native American tribes in over a century.

Dakota State officials were clearly in league with the fossil fuel industry. The North Dakota Governor Jack Dalrymple (a Trump adviser) declared a state of emergency in August, viewing the protesters as a threat. Protest camps were encircled by law enforcement with wire fences and road blocks. ETP hired a private security contractor to infiltrate the camps and plant false reports on social media and local news. In Big Oil rhetoric, Water Protectors were compared to jihadist insurgents.

That same month, at least 27 Native burials were identified on private land directly in the path of the pipeline. Very quickly, on 3rd September 2016, ETP sent several bulldozers to destroy the burials. ETP moved equipment about twenty miles for this special mission of destruction. The protesters, led by women, pushed down fences and threw themselves in front of bulldozers. A white aggressor jumped down from a truck, spraying a line of women and children with CS gas, a chemical that burns skin, eyes, and throats. CS gas can cause blindness.

The baton-wielding invaders also set dangerous attack dogs upon Sioux people, including a child and a pregnant mother. The dogs drew blood. Even praying female protesters were intimidated by police yobs. Wounded victims were carried away screaming. Indignant tribal members and allies drove the guards and dogs away from the scene to avoid further injury.

Two Sioux women praying in front of violent militia on the site of desecrated Sioux ground at Standing Rock. Courtesy Rob Wilson Photography.

Two Sioux women praying in front of violent militia on the site of desecrated Sioux ground at Standing Rock. Courtesy Rob Wilson Photography.

ETP responded with the use of force via a private security company, County police, and National Guard. Armoured personnel carriers arrived with hundreds of militia in October 2016. The big business strategy enforced a media blackout, while injuring hundreds of protesters. Some arrested victims were praying at the time of arrest.

The so-called “law enforcement” used stun guns, batons, rubber bullets, water cannon, chemical spray, and concussion grenades to forcibly remove Native American protesters from their own land (Civil Disobedience). Private white mercenaries maimed people with techno-tools of violence. The Big Oil capitalist predators have no humanitarian principle and no conscience. Female Sioux spokesmen referred to ongoing Army Core lies. Sioux women at Standing Rock filed an injunction to stop the invasive pipeline.

Sioux woman on horseback at Standing Rock Protest, 27th October 2016. Courtesy Ryan Vizzions

Sioux woman on horseback at Standing Rock Protest, 27th October 2016. Courtesy Ryan Vizzions

In late October, police violently evicted the 1851 Treaty Camp that blocked the pipeline construction crews on the highway. The invaders slashed tents, dragging out and beating inmates. They doused victims with CS gas and tear gas, and blasted them with deafening LRAD sound cannons. Many victims were arrested and their belongings confiscated. Those belongings were afterwards returned soaked with urine. This gesture of contempt had the obvious racist implication of “Piss on you.” Protesters were treated as enemies and thugs. They were being called trespassers on their own land, designated in an abused treaty of 1851 (the Fort Laramie Treaty).

On 20th November, the malignant ETP forces used water cannon to spray protesters with water in freezing temperatures. The aggressors also used pepper spray, rubber bullets, and flashbang grenades to target unarmed protesters. More than 200 victims were injured. One Navajo woman lost an eye, becoming permanently disabled. Camp medics saved many lives that night in the struggle against hypothermia and chemical exposure. Hundreds of unarmed protesters were brutalised by ETP thugs. The Lakota Sioux attorney, Chase Iron Eyes, has reported on the situation in a revealing video (What Really Happened at Standing Rock – I Was There).

A total of over 800 Sioux people and allies were arrested, a number of these (including women) being consigned to jail cells (“dog kennels”) with no furniture or bedding in harsh winter conditions. Some Sioux woman, when arrested, were stripped naked by gloating white male police thugs, and left for hours to freeze without clothing in a primitive cell. Identifying numbers in marker pen were scribbled on their arms. The United Nations stated: “Marking people with numbers and detaining them in overcrowded cages, on the bare concrete floor, without being provided with medical care, amounts to inhuman and degrading treatment.”

Protester Sophia Wilansky suffered her arm being almost completely torn off by shrapnel from a grenade. The FBI suggested that she contracted this mishap herself by the use of home-made explosives. This allegation has been strongly contradicted, likewise the “hundreds of pages of lies” contributed by ETP lawyers (Lawsuit Lies). Those lawyers blamed Greenpeace and other environmental groups for inciting eco-terrorism and misleading the public. The Sioux were here represented as being incapable of truth or ability in ecological argument. ETP were the experts on ecology. In contrast, film clips reveal how ETP private militia (“police”) poured injurious pepper spray upon helpless female victims seated on the ground. Assault rifles, batons, grenades, and attack dogs are not the best excuse for false allegations.

Journalist Amy Goodman reported on the protest, using footage showing what the belligerent “security personnel” actually did. She was charged by a state prosecutor with criminal trespass. An offending official sign stated “US Government Property.” This was claimed by protesters as Sioux land, stolen by officious Republicans. The State of Dakota denied all violations. The opponents said that because Sioux were not Christians, they were not entitled to the land. The same militant Christian argument justified ETP militia yobs firing rubber bullets at unarmed women and causing injury.

Subsequent events involved strong support for the Standing Rock Sioux by February 2017, when a thousand or more US army veterans were prepared to protect the victims. Those veterans arrived at Standing Rock to form a human shield protecting non-violent protesters. This defence was trashed by the new Trump administration, who ensured that the Dakota Access Pipeline achieved completion. The pipeline passes under Lake Oahe, the only source of freshwater for the Standing Rock Sioux.

The eco-criminal Donald Trump signed an executive order allowing the pipeline to complete. The Dakota Access Pipeline formed part of an extensive network of polluting industries. In his general presidential policy, Trump proved to be a complicit agent of environmental degradation that will damage large numbers of the white population to a formidable extent.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe sued ETP in March 2020. A federal judge then ordered a full environmental impact assessment of the pipeline. The officially accepted analysis had been proffered by the commercial interests of ETP, also the Army Corps of Engineers. The former assessment was now found to be gravely deficient. Predatory commercial greed, supported by racist bullies, is no proof of any legal justification. The discrepant situation has continued. The Biden administration proved weak in remedying the situation.

America is now faced with severe ecological problems of drought and flooding, as a consequence of unbridled fossil fuel industry output accelerating climate change. There is no means of preventing the climate landslide after so many years of chronic neglect by billionaires, politicians, and innumerable bureaucrats. The future prospectus of Big Oil is a horrifying increase in pollution. Survivors of the gun lobby will not celebrate Big Oil and Trump policy for the deadly losses scientifically predicted in North America. Native Americans never made the same colossal errors.

Bibliography

Allard, Ladonna Brave Bull, Standing Rock Sioux Historian Interview, 2016, online.

Bray, Kingsley M., Crazy Horse: A Lakota Life (University of Oklahoma Press, 2006).

Brown, Zachary, “The Rhetoric and Practice of Scalping,” Journal of the American Revolution, 2016, online.

Brundage, William Fitzhugh, Civilising Torture: An American Tradition (Harvard University Press, 2018).

Chaky, Doreen, Terrible Justice: Sioux Chiefs and U. S. Soldiers on the Upper Missouri, 1854-1868 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014).

Chavers, Dean, Racism in Indian Country (New York: Peter Lang, 2009).

——“Scalping in America,” Indian Country Today, 2018 (online).

——Indian Massacres in the United States (2 vols, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2021).

Clodfelter, Micheal, The Dakota War: The United States Army Versus the Sioux, 1862-1865 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998).

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne, An Indigenous People’s History of the United States (Boston: Beacon Press, 2014).

Estes, Nick, Our History is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indian Resistance (London: Verso, 2019).

Estes, Nick, and Jaskiran Dhillon, eds., Standing With Standing Rock: Voices from the #NoDAPL Movement (University of Minnesota Press, 2019).

Gibbon, Guy E., The Sioux: The Dakota and Lakota Nations (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003).

Hassrick, Royal B., The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society (University of Oklahoma Press, 1964).

Hyde, George E., A Sioux Chronicle (University of Oklahoma Press, 1956).

Jackson, Helen Maria Hunt, A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with some of the Indian Tribes (New York: Harper, 1881; repr. 1993).

Lawson, Michael L., Dammed Indians: The Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux, 1944-1980 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1982).

——Dammed Indians Revisited: The Continuing History of the Pick-Sloan Plan and the Missouri River Sioux (Pierre: South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2009).

Lazarus, Edward, Black Hills White Justice: The Sioux Nation Versus the United States, 1775 to the Present (University of Nebraska Press, 1999).

Lemley, Murray, The Standing Rock Portraits: Sioux photographed by Frank Bennett Fiske 1900-1915 (Terra, 2018).

Lindsay, Brendan C., Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846-1873 (University of Nebraska Press, 2012).

Madley, Benjamin, “Reexamining the American Genocide Debate: Meaning, Historiography, and New Methods,” The American Historical Review (Feb. 2015) 120(1):98-139

——An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe (Yale University Press, 2016).

Madsen, Brigham D., The Shoshoni Frontier and the Bear River Massacre (University of Utah Press, 1985).

Miller, Elizabeth, “Evidence for Prehistoric Scalping in Northeastern Nebraska,” Plains Anthropologist (1994) 39(148):211-219.

Shields, Jana et al, The History and Culture of the Standing Rock Oyate (North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, 1995, online PDF).

Van De Logt, Mark, War Party in Blue: Pawnee Scouts in the U. S. Army (University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

Rare Historical Photos of the Standing Rock Sioux

A Photographic Tribute to Standing Rock

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 80

Copyright © 2022 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.