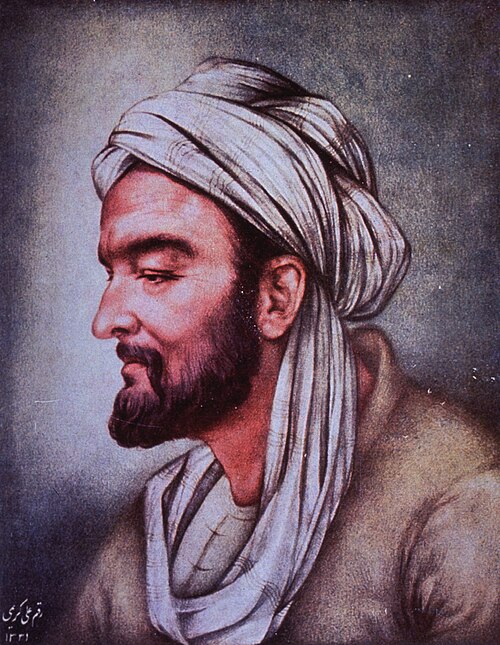

Depiction of Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina (before 980-1037), known in Europe as Avicenna, was an Iranian polymathic philosopher of considerable scope. He was born at a village near Bukhara, capital of the liberal Samanid dynasty, in Central Asia. His father was a local estate governor. The family moved to Bukhara after his birth. Ibn Sina was educated in Bukhara, which possessed advantageous facilities for study (Gutas 2014b:6). By the age of eighteen, he had learned jurisprudence, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, physics, and also philosophy (falsafa) in the Peripatetic (Aristotelian) mould.

Gifted in medicine, Ibn Sina became a physician at an early age. He also gained familiarity with the Metaphysics of Aristotle, at first with difficulty; he assimilated the contents via the commentary of al-Farabi. Ibn Sina early arrived at an independent standpoint in religion. However, he remained a Muslim.

His autobiography relates that his teacher, the mathematician Abu Abdulla al-Natili, possessed merely a superficial knowledge of philosophy. He therefore studied on his own, in logic, mathematics, and astronomy. His self-taught curriculum (apart from medicine) did not impair his abilities. Ibn Sina ranks as one of the most brilliant intellects of his era.

The autobiography has been described in terms of: “centers on the ability of some individuals with powerful souls to acquire intelligible knowledge all by themselves and without the help of a teacher…. is written from the perspective of a philosopher who does not belong by training to any school of thought and is therefore not beholden to defending it blindly, who established truth through his independent verification (hads)” (Dimitri Gutas, “Avicenna ii. Biography,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online). The Arabic term hads is also translated as intuition; however, this word was used by Ibn Sina in relation to his version of the Aristotelian syllogism.

In 997, Ibn Sina gained entry to the palace library when he cured the Samanid ruler (Nuh ibn Mansur al-Samani) of an illness. That library apparently possessed an extensive collection of works, which he researched. A few years later, he started to write his own books, mostly in Arabic. His corpus is extensive.

The life of Ibn Sina was colourful, and at times hazardous. The political conditions in Central Asia and Iran were very unstable; military strife was commonplace. Gaining an administrative post, he moved from Bukhara to Khwarezm, eventually arriving at Hamadan in West Iran, maintaining a career as court physician and political minister (wazir). Dependent on royal patrons, Ibn Sina evidently lived in some degree of opulence.

At Hamadan he suffered a brief period of imprisonment in the political flux, later moving to Isfahan, where the Buwayhid prince Ala’ al-Dawla became his patron. Ibn Sina acted as a physician and scientific adviser to this prince for over a decade, accompanying the ruler on military campaigns, while writing books in his leisure hours. He began the construction of an observatory, a project that was not completed. He died at Hamadan during a military campaign, suffering from colic. His pupil Juzjani reported that Ibn Sina indulged in sexual activity with women; he later gained a reputation amongst detractors for being disposed to slave girls and wine. Ibn Sina is said to have experienced remorse on his deathbed, giving away his possessions.

His works include al-Qanun fi’l-tibb (The Canon of Medicine), which epitomised the medical knowledge of his time, supplemented by his own original observations. The Qanun draws heavily upon the legacy of Galen (Claudius Galenus of Pergamon), a Roman era medic with an extensive output. “As a magisterial exposition of Galenic medicine, the Canon is not unique, nor was it the first in Arabic” (B. Musallam, “Avicenna x. Medicine,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online). However, Ibn Sina ingeniously attempted to assimilate Aristotle to the influential Galenic medicine. His Qanun was translated into Latin, becoming salient as a textbook in European universities until the seventeenth century.

His lengthy and encyclopaedic Kitab al-Shifa (Book of Healing) incorporates logic, the natural sciences, mathematics, and metaphysics. Mathematics is here divided into geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and music. This neo-Aristotelian digest of philosophy and science became famous in a Latin translation two centuries later, creating controversies, censure, and also diverse influences upon the Christian schoolmen, including Aquinas, who frequently cited Ibn Sina (alias Avicenna).

Ibn Sina expressed high praise of Farabi, but was not a copyist. “We see in his system traces of Platonism, Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism, Galenism, Farabianism and other Greek and Islamic ideas. His system is unique, however, and cannot be said to follow any of the above schools. Even al-Shifa, which reflects a strong Aristotelian tendency, is not purely Aristotelian” (Inati 1996:232). In contrast to Farabi and Ibn Rushd, Ibn Sina did not write commentaries on Aristotle, instead contributing original treatises.

His Danishnama-yi ‘Ala’i (Book of Science) is described as the first treatise of Islamic Peripatetic philosophy to be written in the Persian language, being an introductory text for laymen, and dedicated to his patron Ala’ al-Dawla. Exhibiting a less formal style, the author again contradicts the scholastic theologians (mutakallimun), whom he seems to have regarded as primary opponents. See M. Achena, “Avicenna xi. Persian Works,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online.

Ibn Sina’s version of Aristotle was undertaken in an independent spirit of revision. He also incorporated Farabi and Plotinus. A drawback here is that Ibn Sina and other Muslim commentators believed that the confusing text Theology of Aristotle was the culmination of Aristotle’s metaphysics. The Theology is actually an Arabic version of Enneads IV-VI (Adamson 2002). An Arabic redaction of Proclus, meaning Elements of Theology (al-Khayr al-mahd) was also believed to have been composed by Aristotle. “Despite the influence that Neoplatonists such as Plotinus and Proclus played in the formation of the falsafa [philosophy] tradition, Aristotle was most often credited with their innovations” (McGinnis 2010:8). As a consequence, the Arabic Aristotle was “thoroughly Neoplatonised” (ibid:9).

Ibn Sina’s distinctive Peripatetic exposition is regarded as a fusion of Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism, and Islamic theology (kalam), bearing in mind his conflict with theologians.

Avicenna’s epistemology is predicated upon a theory of soul that is independent of the body and capable of abstraction; this proof for the self in many ways prefigures by 600 years the Cartesian cogito. (Quotation from Sajjad H. Rizvi, “Avicenna,” Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy)

The metaphysical system of Ibn Sina is described as “one of the most comprehensive and detailed in the history of philosophy.” The content includes “an underlying Farabian motif, namely, that the quest after philosophical knowledge is for the sake of perfecting one’s soul and hence for the attainment of happiness in this world and the next” (M. E. Marmura, “Avicenna iv. Metaphysics,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online).

Various interpretations of Ibn Sina are in query. “To the unsuspecting and (necessarily) uncritical reader (because of the lack of secondary scholarship), these tendentious writings have presented a view of Avicenna, understandably believed to be well founded, which has been difficult to dislodge. There is thus an Ismaili Avicenna, a (Twelver) Shi’i Avicenna, a mystical Avicenna, and all sorts of gradations within the Sunni Ashari, Shafi’i, and Hanafi, tradition” (Gutas 2014b:x).

The question of mysticism in Ibn Sina has been strongly debated. In his al-Isharat wa’l Tanbihat (Pointers and Reminders), Ibn Sina finishes with a sympathetic review of Sufi mysticism. A feasible interpretation is that he validated Sufism without being a participant, and in terms of his own philosophical system. His lost work called Oriental Philosophy (al-Hikma al-Mashriqiya) or Book of the Easterners (Kitab al-Mashriqiyin) is known via a surviving passage differently interpreted. See, for instance, Nasr 1978:186ff, associated with the view that Ibn Sina was a precursor of later Iranian gnosticism. Cf. D. Gutas, “Avicenna v. Mysticism,” Encyclopaedia Iranica online, here denying any mysticism in Ibn Sina, interpreting this exponent as being rooted in Aristotelian rationalism.

Bibliography

Adamson, Peter, The Arabic Plotinus: A Philosophical Study of the “Theology of Aristotle” (London: Duckworth, 2002).

Adamson, Peter, ed., Interpreting Avicenna: Critical Essays (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Adamson, Peter, and Richard C. Taylor, eds., The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Gohlman, William E., ed. and trans., The Life of Ibn Sina: a critical edition and annotated translation (State University of New York Press, 1974).

Goodman, L. E., Avicenna (1992; new edn, Cornell University Press, 2005).

Gutas, Dimitri, Avicenna and the Aristotelian Tradition (1988; second edn, Leiden: Brill, 2014a).

——–Orientations of Avicenna’s Philosophy: Essays on his Life, Method, Heritage (New York: Ashgate, 2014b).

Inati, Shams, “Ibn Sina,” chapter 16 in S. H. Nasr and O. Leaman, eds., History of Islamic Philosophy Pt 1, (London: Routledge, 1996).

Janssens, Jules, An Annotated Bibliography on Ibn Sina, 1970-1989 (Leuven University Press, 1991).

——–An Annotated Bibliography on Ibn Sina: First Supplement, 1990-1994 (Louvain: Federation Internationale des Instituts d’Etudes Medievales, 1999).

McGinnis, Jon, Avicenna (Oxford University Press, 2010).

McGinnis, Jon, ed., Interpreting Avicenna: Science and Philosophy in Medieval Islam (Leiden: Brill, 2004).

Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines (revised edn, London: Thames and Hudson, 1978).

——–“Ibn Sina’s ‘Oriental Philosophy’,” chapter 17 in Nasr and O. Leaman, eds., History of Islamic Philosophy Part 1 (London: Routledge, 1996).

Nusseibeh, Sari, Avicenna’s Al-Shifa: Oriental Philosophy (New York: Routledge, 2018).

Rahman, Shahid, Tony Street, Hassan Tahiri, eds., The Unity of Science in the Arabic Tradition (New York: Springer, 2008).

Street, Tony, Avicenna: Intuitions of the Truth (Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society, 2002).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

April 21st 2010 (modified 2021)

ENTRY no. 18

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.