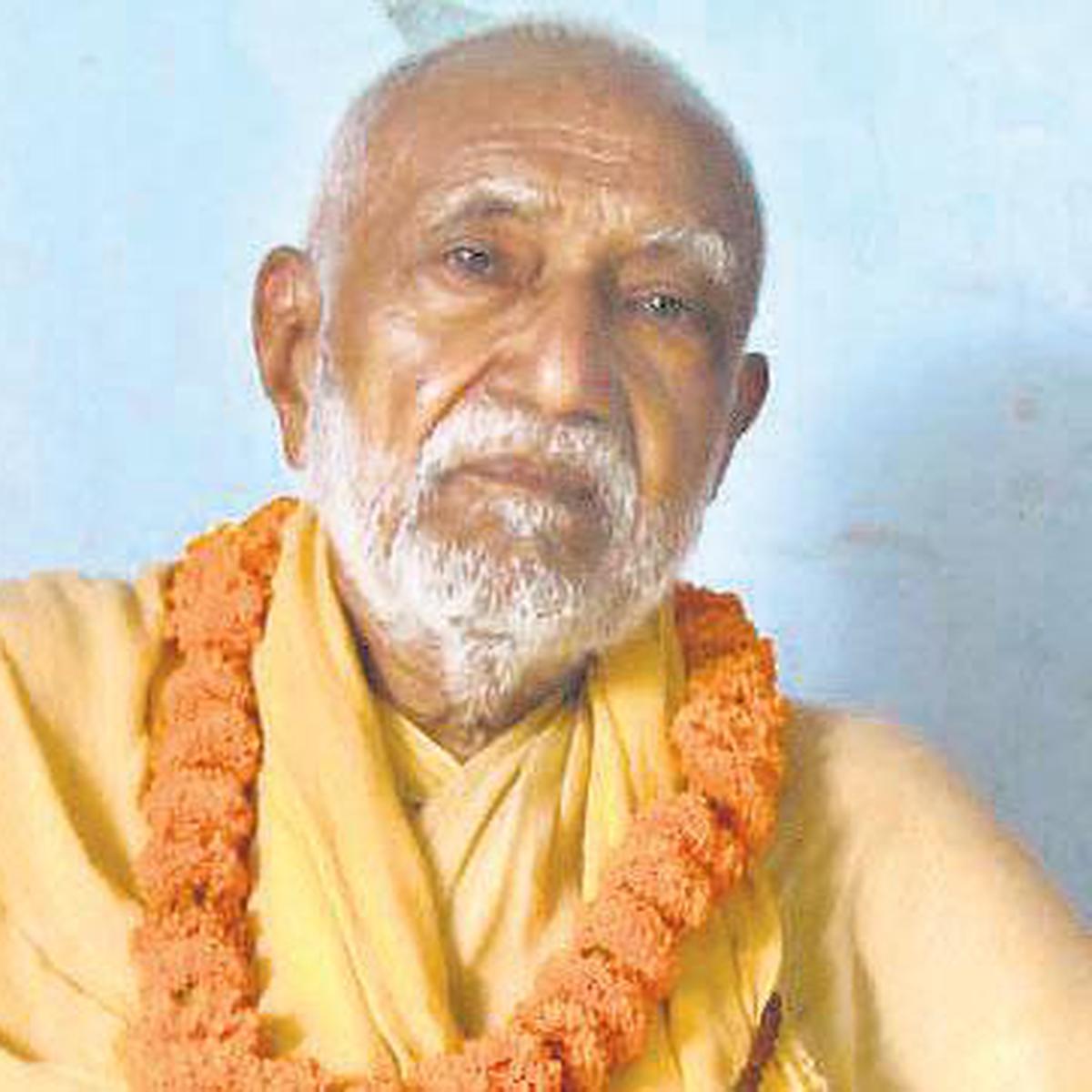

Guru das Agrawal

Two recent Hindu monks, who fasted to death for ecological reasons, comprise a striking chapter in the struggle against industrial pollution. The ex-professor G. D. Agrawal, and his predecessor Nigamananda Saraswati, were both concerned to save the Ganges (Ganga) River from pollution.

The Ganges is the fifth most polluted river in the world, with the ambivalent reputation of being the sacred river of Hinduism. However, religion is not guiding the fate of this river, but instead government error, industrial greed, and soaring population.

The Ganges basin supports over half a billion people. The sacred river emerges in the Himalayas, afterwards becoming sludge via urban incursions, emptying into the Bay of Bengal. Most of the original forest and vegetation has disappeared from the basin, now intensively cultivated for an increasing human population. The Yamuna (Jumna), a major tributary of the Ganges, is contaminated by cities like Delhi, where the population has doubled since 1991.

About 80 percent of the pollution comes from sewage, disastrously mismanaged, despite the presence of sewage plants. Scores of cities and towns dump untreated sewage into the river. Less than a quarter of the sewage is treated. The river is drastically afflicted by sewage foam. In addition, nearly 500 million litres of untreated industrial waste, from factories and farms, are dumped into the Ganges on a daily basis. The National Mission for Clean Ganga, based in Delhi, has estimated pollution from industries at 20 percent of the total.

The most polluted stretch of the Ganges is from Kanpur to Varanasi. At Kanpur, over 300 leather tanneries discharge toxic waste into the river; Kanpur is said to be the dirtiest city in India. Chromium is used in tanning; this chemical infiltrates the river. Chromium poisoning is thought to be the causative agent increasing deformities amongst new born babies. Ecologists say that pollution is killing Kanpur. The river can turn black. This occurs because of national and international demand for superior leather; the export trade is highly rated by economists.

The notorious fate of cows, in barbaric abbatoirs, has been a component of the leather industry, which produces fancy handbags, belts, and shoes for the rich. The “sacred cow” is one of the contradictions in the Indian environment. Helpless cows have long been beaten, abused, and poisoned to make leather for high street shops. The leather trade has recently been hit by a conservative Hindu reaction. However, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has sought to double lucrative leather industry revenues by 2020.

At Kanpur, it is now illegal to slaughter cows. Only carcases of animals that have died naturally, or by roadkill, can be utilised by tanneries (mostly owned by Muslims). Many Dalits (formerly untouchables) work in tanneries. The government employs Dalits in waste removal and the skinning of dead animals. These activities amount to hereditary occupations imposed by the caste system.

A 2013 report stated that tanneries create only 8 percent of effluents in the Ganges. Some say the percentage is now less. Tanneries complain that they have been made a scapegoat for the government failure to rectify the huge sewage problem. There are over a thousand industrial units, including tanneries, between Kanpur and Patna. The sugar and paper industries, along with distilleries, are some of the drawbacks.

Some factories, concerned about controls, have been contradicted by the situation of different official monitoring departments that do not work in unison. Free-flowing water is afflicted by mismanagement. Arsenic is one infiltrator. High levels of disease-causing bacteria are found in the abused Ganges.

In 1985, under Rajiv Gandhi, the Indian government commenced the Ganga Action Plan. Little progress was made. Fashionable theories of economics and urban development are still a hindrance. The Action Plan was continually wrecked by dams, lost water, official indifference, bungling, and diversions. In addition to drawbacks evident on the Ganges and Yamuna, tributary rivers also suffered. This trend resulted “in 795 dams and 181 barrages/weirs that were obstructing and diverting water from almost every tributary in the entire Ganga basin.” Miseducated politicians are a danger to the populace.

Varanasi

When the Ganges reaches the holy city of Varanasi (Benares), the river is lethally contaminated, being described as a sewer. Many pilgrims bathe in the unhealthy water, regarding immersion as a sacred rite. Scientists warn that the presence of coliform bacteria in water means potential disease, a situation aggravated by large quantities of sewage. Scientists discovered that the Ganges has “a faecal coliform count of more than 1.5 million per 100 ml of water.” In contrast, water that is safe for bathing should not contain more than 500 faecal coliform per 100 ml. This detail comes from an Australian source describing the Ganges as the “holy river from hell.”

The vast number of people who bathe in the Ganges risk contracting hepatitis, typhoid, cholera, and amoebic dysentery. Governmental incompetence and wrong decisions are highlighted by objectors. India’s plan to clean up the Ganga is seriously flawed. This is the Kali Yuga of technology, an unprecedented reverse into environmental pollution.

What is now called the plastic trail of the Ganga is largely ignored by the Indian government. Reports describe huge piles of plastic garbage at the edge of nearby towns and villages. This industrial product goes into drains and is then ejected into the sea, where havoc is caused to the oceans.

In other Asian zones, rivers likewise conduct plastic waste to the seas. Most of the 20 worst polluting rivers in the world are Asian; these account for 67 per cent of the global total of plastic waste. Some plastic zones in oceans are larger than major cities. The scale of desecration is vast. The global foodchain is being affected by the gigantic amount of plastic waste existing in contaminated oceans. The ocean facts are now very daunting.

In 2014, the new Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a pledge, allocating 20 billion rupees to clean up the Ganges, saying he would succeed where all previous governments had failed. He referred to Ma Ganga (Mother Ganges). However, the Ganga Rejuvenation project has since failed to cope with the extensive sewage problem. According to some sources, less than a quarter of the funds have actually been used. The project is certainly behind schedule. Ecologists remind that officially favoured dams disrupt the natural flow of water. Too much water is removed for farming.

A formidable complication is uncontrolled sandmining, which has been killing rivers across South Asia and China. This activity involves the extraction of sand and rocks from riverbeds for construction work. “Reporting alleged sandmining is the most dangerous thing a journalist can do in India.” Journalists have been murdered, allegedly by the illegal sandmining mafia in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and elsewhere.

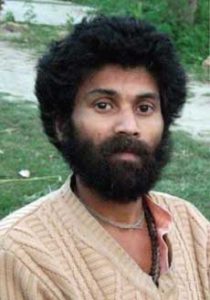

Nigamanand Saraswati

In February 2011, a courageous monk commenced his last “hunger strike” at Hardwar, a sacred town in the Himalayan boundaries, on the banks of the Ganges. He was complaining at the illegal and pollutive sandmining and quarrying in the Ganges riverbed. Nigamanand Saraswati (1976-2011) was a mendicant sadhu who settled at the hermitage of Maitri Sadan, on the outskirts of Hardwar. His affiliation was to the Shankara Order; he was a scholar of Vedic and Vedantic literature. He and other young Saraswati monks at that site were committed to a struggle against bureaucratic corruption and environmental destruction.

Nigamanand and his colleagues undertook two fasts in 1998, one lasting for over two months. The objective was to gain support for the elimination of illegal mining in the Kumbh Mela (religious fair) zone of Hardwar. Their method was the non-violence (satyagraha) associated with Mahatma Gandhi. Thirteen years later, Nigamanand was hospitalised on the sixty-eighth day of his fast in late April, 2011. Soon after, he was allegedly poisoned by a pro-mining opponent. He was treated with antidotes, continuing his fast. Nigamanand died of dehydration (or poisoning) in June. Subsequently, the local Uttarakhand government belatedly proscribed riverbed mining in the vicinity of bathing ghats at Hardwar.

G. D. Agrawal

G. D. Agrawal (1932-2018) was a professor of environmental engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur. He became a pioneering ecological activist, inspiring eco-lawyers and others. Agrawal was distressed at the condition of the Ganga, which he researched in detail. He was a patron of Ganga Mahasabha, founded in 1905, an organisation demanding the removal of dams (they initially opposed the British damming of the Ganga at Hardwar). Agrawal urged that government funds should be allocated to sewer networks, sewage treatment plants, pumping stations, and other facilities including electric crematoria (to avoid the customary disposal of corpses in the sacred river).

Agrawal undertook two hunger strikes in 2008 and 2009, being successful in persuading the government to cancel the project of a hydroelectric dam on the Bhagirathi river, one of the source tributaries of the Ganges. In 2009, he was fasting at Uttarkashi for the purpose of emphasising that the free-running Ganga should not be impeded. This was the only stretch of the great river still undisturbed by human activity. An opponent was a politician in Uttarakhand, namely Diwakar Bhatt, who alleged foreign interference in these anti-hydro measures, which he deemed a hindrance to national development. Bhatt branded Agrawal and his colleagues as traitors. This industrial perspective speaks volumes for river pollution.

Agrawal was close to death on the 38th day of his severe fast in February 2009. The Ministry of Power then ordered suspension of work on the Loharinag Pala Hydropower Project. A letter was despatched to Agrawal, who accordingly ceased his fast the next day. The government declared the Ganges to be a National River, and created a monitor known as the National Ganga River Basin Authority (NGRBA), whose chairman was the Prime Minister Manmohan Singh.

In 2010, the Indian government commenced a campaign to ensure that, by 2020, no untreated municipal sewage or industrial waste would enter the 1,560 mile Ganga river. This was Mission Clean Ganga, moving away from earlier focus upon a few polluting cities. The plan seemed promising, but proved a failure.

In 2011, Agrawal renounced all his possessions to become a sannyasin of the Shankara Order. He was initiated by Swarupananda Saraswati at Joshi Math. He was thereafter often known as Swami Gyanswaroop Sanand. The transition in identity is significant. At the age of 79, Agrawal had experienced acute frustration in academic and official channels. Contemporary university education produced politicians and economists with tunnel vision. The Modi government was inspired by a discrepant agenda of Western technology and insular Hindu nationalism.

Swami Sanand fasted again in 2012. In June 2013, he commenced a fast in reaction to apathy demonstrated by the NGRBA. The 101st day of his fast was September 21, when he stopped taking water. The government demonstrated indifference. However, three conscientious members of the elite NGRBA resigned as a consequence of the deplorable situation.

Narendra Modi

In 2017, a CAG report of the Ganga Rejuvenation (a nominal cause of Narendra Modi) amounted to an indictment of lax official performance. Deficit included the fact that coliform levels in all cities of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal were very high, varying from between six to 334 times higher than safety prescriptions.

Swami Sanand, alias Agrawal, waited patiently for almost four years, becoming totally disillusioned with officialdom. During February to September 2018, he wrote six letters to Prime Minister Narendra Modi. None of these communications received a reply, nor even an acknowledgment. Political rhetoric had no answer to rejuvenation issues. Six years earlier, Modi had tweeted in support of Agrawal’s fast in 2012. The interest was not ongoing.

In his letters, Swami Sanand urged Modi to introduce a Ganga Act, and if necessary, via a Presidential ordinance. He advised the Prime Minister to cancel all hydropower projects planned, or under construction, in Uttarakhand. He emphasised a ban on the extraction of sand and boulders from the Upper Ganga Basin, especially the Kumbh Mela zone in Hardwar. He urged that Modi should elect a council of twenty persons devoted to the Ganga cause, “who shall pledge to work only in the interest of River Ganga, and who shall hold the final word in relation to all actions pertaining to River Ganga” (quote from online feature How the Modi government went horribly wrong on Ganga Rejuvenation).

Swami Sanand (Agrawal) was also concerned about deforestation. The monk complained that the Modi government had not taken a single action to rescue the polluted river. He was firm with Modi: “Till now you have only thought on the point of earning profits from Gangaji (Ganges).” He apparently emphasised the priority of the Shankara Order in an age of decadent values.

In June 2018, Agrawal commenced a severe fast, intended as a complaint against the Indian government failure to rejuvenate the Ganga. Abstaining from food, he drank water with honey and lemon juice. A government minister contacted Agrawal, advising him to relinquish his fast. The monk refused to do so unless his demands were met. He died from starvation in October 2018, after nearly four months of severe fasting at the age of 86. The government did nothing to concede his requests. The situation is sufficiently clear to permit a strong adverse judgment on political rhetoric.

Agrawal died in hospital at Rishikesh. He told one of his associates: “I have lost, but maybe you can fight.” His followers and admirers then planned a march from Delhi to Varanasi, the sacred city of the Ganga, and the constituency of Narendra Modi. This group reported false claims about the government conceding demands of Agrawal. In reality, none of the demands were met by the acutely industrialised government.

The day before Agrawal’s death, the Ministry of Water Resources provided a notification of further delay. The Ganges would have to wait another three years for any improvement to occur in respect of enhanced flow, a benefit “at the mercy of project owners and Central Water Commission, both suffering from abject track record and conflict of interests” (quote from How the Modi government went horribly wrong). The afflicting Ministry gesture is further described by an Indian critic in terms of “a tokenism, at best with unscientific basis, and many other problems associated with it.”

In a fashionable tweet, Modi expressed sorrow at the death of Agrawal. The Prime Minister is noted for pursuit of a discrepant policy in relation to Ganga Rejuvenation. Modi opted to relax environmental regulations and to favour industrial growth, including controversial hydroelectric dams. He even lifted restraints upon new industrial activity in the most polluted regions of India. Modi pandered to extensive commercial interests, alienating ecologists in the process.

The two fatally fasting monks (Nigamananda and Sanand) represented a much older tradition of response to nature. The Indian world of ascetics and monks was not an ecological burden, creating no killer industries. Celibate restraint contrasts with householders who boost population growth to excess (currently over a billion in national terms). Sadly, the monks are regarded by contemporary technological society as an insignificant and eccentric minority. Celibacy is perhaps what is most needed in Asia, despite the invasion of monastic Tibet by the Chinese military in the mid-twentieth century, an event maintaining brutal suppression, and contributing to ecological catastrophe in the Far East.

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

Entry no. 76

Copyright © 2018 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.