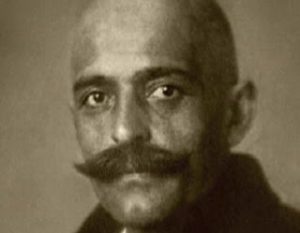

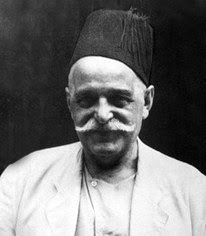

Georgii Ivanovich Gurdjieff

Georgii Ivanovich Gurdjieff (circa 1866-1949) is a controversial figure variously described as an occultist, mystic, and charlatan. His early life is obscure. He was born at Alexandropol (Gumri), a Russian garrison town in Armenia. An Armenian Greek, he was reared to beliefs of Armenian Christianity. His father Giorgios Giorgiades, a Greek cattle herdsman, also functioned as an ashokh or bardic poet. The repertory of Giorgiades extended to the Turkic oral tradition of Caucasia, in which strong Islamic elements figured. The bardic recitals are viewed as a strong influence upon the young Gurdjieff.

This entity does not gain secure factual profile until his move to the big cities of Western Russia in 1912. Gurdjieff’s legendary early career was described, by himself, in terms now regarded as a mixture of fact and storytelling, and by some as sheer parable (see Inventors of Gurdjieff). He is associated with Sufi dervish and Tibetan Buddhist environments. Gurdjieff claimed to have visited Tibet, making much of his encounter with the Sarmoung monastery, an obscure location in Central Asia to which he attributed his deepest inspiration. He became mistakenly identified with “secret agents” working in the Tibetan political sector; for instance, Lama Aghwan Dordjieff (d.1938) was a completely separate entity, despite the confusing account relayed by Rom Landau.

Gurdjieff moved from Central Asia to Moscow and St. Petersburg (Petrograd). That same year of 1912, he married Julia Ostrowska (d.1926), a Polish woman. He conducted group meetings in both cities, expressing themes now well known via the reporting of his Russian disciple Piotr D. Ouspensky (d.1947), a writer and lecturer associated with the Theosophical Society. Ouspensky at first assumed that Gurdjieff was just another occultist, of whom there were many at this time. He afterwards altered his assessment, viewing Gurdjieff’s tuition in terms of an “unknown teaching.” Ouspensky’s book on the subject (In Search of the Miraculous) has been very influential.

A basic teaching of Gurdjieff emerges: man is mechanical and effectively asleep in relation to real life. He asserted that most men cannot develop or progress; the process involved is so difficult that advancement is ordinarily impossible. He claimed to provide a means of achieving this development via the Fourth Way, an approach departing from established religious routes. Ouspensky was much impressed by this concept (and later used the phrase “fourth way” more intensively than his inspirer); he left the Theosophical Society to align himself with Gurdjieff. After a few years however, a rift commenced to show. Ouspensky eventually opted to become a teacher of what he had learned from Gurdjieff.

Meanwhile, the First World War and the Bolshevik Revolution caused chaos in Russia. Gurdjieff then retreated south, staying at Essentuki, a town adjoining the Caucasus. In August 1918, he made a carefully planned departure, in the face of civil war. On the pretext of an archaeological field study, he led a party of his followers (without Ouspensky) across the Caucasus in very dangerous conditions. They reached the port of Sochi, where a number of them defected. Gurdjieff and five companions moved on to reach the safety of Tbilisi (Tiflis) in Georgia.

Gurdjieff now created his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man. He had commenced to choreograph the “sacred dances,” an activity said to be “based on movements and gestures which had been handed down by tradition and paintings in Thibetan [sic] monasteries where he had been” (quote from C. E. Bechofer Roberts, Journey Through Georgia).

Further political unrest caused Gurdjieff to move to Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1920. That city was flooded with Russian refugees at this period. A temporary reconcilement occurred between Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, who had gained his own group of Russian students. Together, they made several visits to the Mevlevi dervishes. However, they departed in different directions. Gurdjieff went to Germany, where his plans met with obstruction. Ouspensky moved to England, where he commenced a successful role as a lecturer on the “Work,” as Gurdjieff themes became known.

Ouspensky found that many of his new English students developed a strong interest in Gurdjieff, a trend which gained impetus when the Armenian gave a talk at London in February 1922. Gurdjieff spoke in Russian, via an interpreter, to sixty British intellectuals, including Alfred R. Orage, who proved very enthusiastic. Orage accepted Gurdjieff as his teacher from then on; he was editor of the London weekly review The New Age, an influential organ of literary and political interest. Both Orage and his teacher have been described as black sheep philosophers.

Later that same year, Gurdjieff moved to France, where he acquired (via a benefactor) the Chateau du Prieure, a mansion at Fontainebleau, some forty miles from Paris. This property became the new site for his Institute, and the setting for two contingents of pupils, meaning the Russian and British. The new British recruits notably included Orage and Dr. Maurice Nicoll, a psychiatrist of Harley Street and an acquaintance of Jung. Dr. Nicoll subsequently gravitated back to Ouspensky, whereas Orage became a strong supporter of Gurdjieff’s activity, later acting as his emissary in America.

Gurdjieff’s dancers, 1920s

The Prieure (Priory) became a scene of manual work, including construction of the Study House, the interior of which resembled a dervish tekke or meeting place, lavishly decorated with Eastern rugs. The Study House was the focus for “sacred dances” supervised by Gurdjieff. The gymnastic programme far outweighed any formal teaching; Gurdjieff’s approach contrasted with the lecturing role associated with Ouspensky. The latter made visits to the Priory until 1924, but thereafter strongly diverged, even advising Nicoll and others to dissociate from Gurdjieff. The Russian ex-pupil reacted to the dance programme and the unpredictability inherent in Gurdjieff’s temperament.

The Armenian gained many French critics; much of the disparagement was based on rumour. Gurdjieff was said to be a Freemason and a hypnotist. His reputation as a hypnotist has some basis in his own admissions. The gossip and slander moved to an extreme, becoming markedly erroneous in relation to Katherine Mansfield, an authoress from New Zealand who died at the Priory in January 1923. She was a terminally ill victim of tuberculosis. Gurdjieff was not the cause of her death.

One of the most revealing sources is Professor Denis Saurat, who gained a lengthy private interview (involving an interpreter) with Gurdjieff in February 1923. His account discloses that Gurdjieff was capable of marked courtesy, “and gave not the smallest impression of being a charlatan.” However, the same report attests that English pupils were disconcerted by the Priory routine, which entailed protracted manual labour and no adequate explanation. Saurat never saw Gurdjieff again. Becoming influenced by the views of his friend Orage, in later years Saurat credited Gurdjieff with the spiritual status of lohan, a term deriving from Chinese Buddhism. This theory is not everywhere accepted.

In 1924, Gurdjieff was active in America, as an impresario of “sacred dance.” Some of the audience were impressed by the unusual performances of his pupils, who demonstrated considerable control and coordination. As a consequence, he gained many American followers. However, after his return to France that same year, he met with a motor accident, suffering severe head injuries. Although he recovered quickly, this event clearly affected him strongly. He thereafter relegated the dance movements, instead adopting the vocation of a writer. He also took more recourse to alcohol than previously, favouring vodka and armagnac.

For the next decade or so, Gurdjieff did much writing. He authored “Three Series,” including the “autobiographical” Meetings with Remarkable Men, and the more lengthy Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. The lastmentioned creation is a bizarre mythology, incorporating a strong critique of Western society. These works were not published during his lifetime. The only writing of Gurdjieff to achieve print (prior to his death) was a disconcerting book entitled The Herald of Coming Good (1933), which he himself afterwards withdrew.

Gurdjieff’s debts were a primary factor in losing the Priory, which he was obliged to vacate in 1932, thereafter living solo in Paris. He made several visits to New York during the 1930s. Gurdjieff became notorious amongst some of his admirers for requesting money. His general reputation as an occultist gained reference in a bestselling work by journalist Rom Landau, who believed that Gurdjieff was a hypnotist.

Critics have since targeted the subject’s sexual activity, of uncertain extent, but known to have involved a number of illegitimate children. This matter has been considered reprehensible, because the known women involved were his pupils. The contested encounters of Gurdjieff apparently derived some inspiration from his eccentric belief that women need sexual contact with men to acquire a soul.

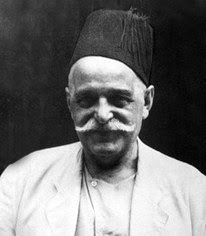

Gurdjieff in his later years

During the Second World War, Gurdjieff lived in Paris. At this period, he gained French followers for the first time, teaching in group meetings at his apartment. He also revived his interest in sacred dance “movements.” Gurdjieff now charitably assisted poor people outside his following. After the war, he gained further interest from American and English admirers, including John G. Bennett, an English neo-Ouspenskyan who had numerous followers.

In 1948, Gurdjieff suffered another motor accident, although not as severe as the first one. He recovered with surprising speed, but the following year, his health deteriorated, leading to his death. After his decease, his pupil Jeanne de Salzmann organised his following into a movement, a number of Gurdjieff centres resulting in different countries.

Bibliography:

Gurdjieff, G. I., Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (London, 1950).

——–Meetings With Remarkable Men (London, 1963).

Landau, Rom, God is My Adventure (London, 1935).

Moore, James, Gurdjieff: A Biography (Shaftesbury, 1991).

Nott, Charles S., Teachings of Gurdjieff: A Pupil’s Journal (London, 1961).

——–Journey Through This World (London, 1969).

Ouspensky, P. D., In Search of the Miraculous (London, 1950).

Taylor, Paul Beekman, Shadows of Heaven: Gurdjieff and Toomer (Maine, 1998).

——–Gurdjieff and Orage: Brothers in Elysium (Maine, 2001).

——–Gurdjieff’s Invention of America (Utrecht, 2007).

——–G. I. Gurdjieff: A New Life (Utrecht, 2008).

Webb, James, The Harmonious Circle: The Lives and Work of G. I. Gurdjieff, P. D. Ouspensky, and Their Followers (London, 1980).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

ENTRY no. 49

Copyright © 2012 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.