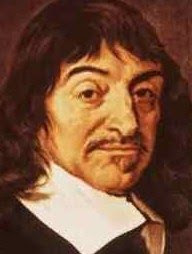

Rene Descartes

Rene Descartes (1596-1650) is often described as the founder of modern philosophy. Born at the French town of La Haye, between Tours and Poitiers, his father was one of the local landed gentry. The boy was sent to boarding school, meaning the Jesuit college of La Fleche, where he stayed for eight years. The Jesuit curriculum encompassed the classical humanities and the prevalent Aristotelian Scholasticism. Following the wishes of his father, in 1616 Descartes took a degree in law at the University of Poitiers; however, he did not pursue the paternal profession. Instead he reacted to academic studies, rejecting much of what he had been taught.

In 1618, Descartes opted for military enlistment, like many others of his social class at this time of divisive religious wars. Moving to the Netherlands, he became a soldier or engineer in the army of Prince Maurice of Nassau. While stationed at Breda that year, he formed a friendship with the Dutch mathematician Isaac Beeckman (1588-1637). Extant letters of Descartes reveal that Beeckman “roused me from my state of indolence and reawakened the learning which by then had almost disappeared from my memory” (Cottingham 2000:100). Descartes also referred in those epistles to his project of a new science providing “a general solution of all possible equations involving any sort of quantity” (ibid:99).

Moving to Germany for further military service, in 1619 he experienced three vivid dreams reported by his seventeenth century biographer Adrien Baillet. One passage reads: “Beginning to interpret the dream while still asleep, he considered that the encyclopaedia signified all the sciences collected together, and that the anthology of poetry indicated philosophy and wisdom combined” (ibid:101-2). The famous “method of doubt” evidently originated in his belief, rooted in a dream experience, that “he was destined to complete the unfinished ‘encyclopaedia’ of the sciences” (ibid:102).

The evocative dreams superseded logic in this scenario. These dreams inspired Descartes to seek a new method of science and philosophy. Afterwards moving to Paris, and making other journeys, Descartes devoted himself to the private study of various sciences. He commenced to write an unfinished treatise on method (Rules for the Direction of the Mind). He sold his ancestral property to secure (via bonds) a workable income for many years after. In 1629, Descartes moved back to the Netherlands, a country then associated with unusual freedom of expression. Residing there for twenty years, he retained a habit of being frequently on the move, living in Amsterdam, Leiden, and other places.

Descartes remained a Roman Catholic, discernibly of an avant-garde type. He wanted to show that the “new physics” could explain the world without relying upon the terminology of Scholastic Aristotelianism, a problem “so entrenched in the intellectual institutions of Descartes’ time that commentators argued that evidence for its truth could be found in the Bible” (Justin Skirry, “Rene Descartes: Overview,” Internet Encyclopaedia of Philosophy.

He composed a treatise on cosmology and mechanistic physics entitled Le Monde (The World). This was ready to go to press in 1633. A drawback then arose. Descartes had utilised Copernican heliocentric theory in his treatise; he now discovered how Galileo (1564-1642) had been condemned that year in Rome for contesting the conventional belief that the earth was the centre of motion. In a mood of caution, Descartes decided not to publish Le Monde. “Indeed, he first decided never to publish anything at all; but the despair did not last” (Daniel Garber, “Rene Descartes: Life,” Routledge Encyclopaedia of Philosophy).

A few years later, Descartes published in French three scientific essays, the Meteorology, Optics, and Geometry (1637). These accompanied his anonymous Discourse on Method, intended as an introduction. The collection became well known. The subsequent Latin work Principia Philosophiae (1644) describes metaphysics, an extending physics, and other sciences. This significant text of Descartes proved influential amongst scientists (including Isaac Newton). However, the physics employed here transpired to be limited in application. Descartes viewed metaphysics as the root of his endeavour to combine philosophy and the sciences.

His two most famous works are Discourse on Method (1637) and the Meditations on First Philosophy (1641). These reveal Descartes as a rationalist who strongly believed in the existence of God, while at the same time innovating concepts foreign to most theologians. His esteem for mathematics is well known:

Existing philosophy (the dominant form of which was the Christianised Aristotelianism of the scholastics) is, he claims, not really knowledge, for it lacks the certainty without which there is no knowledge, and which is currently found only in mathematics. (Moriarty 2015:xii)

Reliance upon mathematics was prone to error, leading Descartes into the questionable activity of vivisection. He is elevated, in the history of philosophy, for his theories about the distinction between mind and matter. The most common description of this complexity is “Cartesian dualism.” The accompanying “method of doubt” signifies the rejection of anything that can be logically doubted, for the purpose of finding certainty.

The Cartesian axiom cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”) was confirming a factor beyond doubt, serving to elevate the importance of mind and self-consciousness. The argument of Descartes was pitched against the emerging scepticism associated with Michel de Montaigne. Like Francis Bacon, Descartes was also in strong opposition to the official Aristotelian philosophy of the academics. He exercised a different angle to that of the British empiricist. Nevertheless, Descartes possessed a strong empirical streak, which he took too far, currently arousing criticism in relation to his animal experiments. There is now a difference discernible between “romantic” and “realist” versions of this philosopher, an issue formerly obscured.

“Descartes claimed that he had taken the doubts of the sceptics further than the sceptics had taken them, and had been able to come out the other side” (Williams 1996:xv).

Descartes was basically remote from the academic milieu, preferring a life of research away from both career status and social distraction. His citizen status tends to be emphasised by the situation in which he addressed a letter to academics of the Sorbonne, a letter appended to the Meditations. His motive appears to have been that of gaining textbook status in the university. A commentary says:

The awkwardness of Descartes’s seeking the acceptance and use of his Meditations by teachers is amplified by the fact that he was not a teacher himself. Consequently, his seeking ‘textbook’ status would have very likely been viewed by those Learned Men as being a bit pretentious. He was, it could be said, a freelancer with no academic or political ties to the university…. Although the Meditations seems to have been endorsed by the Sorbonne, it was never adopted as a text for the university. (Kurt Smith, “Descartes’ Life and Works,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

The same book subsequently became more famous and more cited than the majority of texts known to the Sorbonne. Meanwhile, the Dutch Calvinist theologian Gisbertus Voetius (1588-1676) became a major opponent during the 1640s. He was the prestigious rector of Utrecht University. Voetius incited another academic to publish a lengthy personal attack upon Descartes, here dogmatically viewed as a route to atheism. Descartes composed the retaliatory Open Letter to Voetius (1643). Voetius subsequently suffered a setback when his accomplice disowned the attack, revealing that Voetius was the cause of the hostility. A later episode involved opponents at Leiden University. See further Problems with Calvinist Theologians.

After some hesitation, in 1649 Descartes accepted an invitation from Queen Christina of Sweden to attend her court in Stockholm. She requested him to teach her philosophy, a role entailing the inconvenient hour of five in the morning. Descartes tragically died at this juncture. Some accounts state the cause as pneumonia, However, poisoning by a hostile Catholic priest has also been suggested. In a letter dated January 1650, Descartes commented: “I desire only peace and quiet, which are benefits that the most powerful monarchs on earth cannot give” (Cottingham 2000:105).

Bibliography:

Ariew, Roger, Descartes and the Last Scholastics (Cornell University Press, 1999).

——–Descartes Among the Scholastics (Leiden: Brill, 2011).

Broughton, Janet, Descartes’s Method of Doubt (Princeton University Press, 2002).

Broughton, Janet, and John Carriero, eds., A Companion to Descartes (Oxford: Blackwell, 2008).

Clarke, Desmond M., Descartes: A Biography (Cambridge University Press, 2006).

Cottingham, John, “Descartes” (93-134) in R. Monk and F. Raphael, eds., The Great Philosophers (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2000).

——– Cartesian Reflections: Essays on Descartes’s Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2008).

Cottingham, John, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Descartes (Cambridge University Press, 1992).

Cottingham, John, et al, The Philosophical Writings of Descartes (3 vols, Cambridge University Press, 1984-91).

Garber, Daniel, Descartes Embodied (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Gaukroger, Stephen, Descartes: An Intellectual Biography (Oxford University Press, 1995).

——–Descartes’ System of Natural Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Gaukroger, Stephen, John Schuster and John Sutton, eds., Descartes’ Natural Philosophy (London: Routledge, 2000).

Maclean, Ian, trans., A Discourse on the Method of Correctly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking Truth in the Sciences (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Moriarty, Michael, trans., Rene Descartes: Meditations on First Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2008).

——–trans., The Passions of the Soul and Other Late Philosophical Writings (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Rodis-Lewis, Genevieve, Descartes: His Life and Thought, trans J. M. Todd (Cornell University Press, 1998).

Williams, Bernard, Descartes, the Project of Pure Enquiry (Hassocks: Harvester Press, 1978).

——–introductory essay to John Cottingham, ed., Descartes: Meditations on First Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

May 2010, modified 2021

ENTRY no. 21

Copyright © 2021 Kevin R. D. Shepherd. All Rights Reserved.