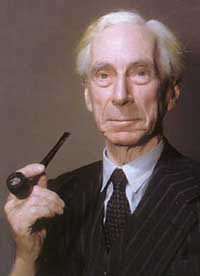

Bertrand Russell

One of the most influential modern philosophers was Bertrand Russell (1872-1970). Some commentators say that he was the dominant figure in twentieth century philosophy. This being so, one is obliged to probe some aspects of his career.

Bertrand Russell was the grandson of Lord John Russell, being reared in a British aristocratic milieu, and eventually inheriting the status of an Earl. However, he allied himself with the Labour Party, being radical in his views. At Cambridge he studied mathematics, a subject which he adapted to philosophy. In 1898, Russell abandoned his neo-Hegelian idealism in favour of realism as the “new philosophy of logic.” He acknowledged the importance of science in this transition.

His early work Principles of Mathematics (1903) is famous for contending his subject in terms of a close relationship to logic. This stance has been described as logicism, meaning the view that mathematics is significantly reducible to formal logic. Russell arrived at his basic view of “mathematical logic” quite independently of the obscure Gottlob Frege (1848-1925), the German mathematician of Jena University who converged in this form of conceptualism (or logicism).

In collaboration with Alfred North Whitehead, Russell subsequently produced Principia Mathematica (1910-13), a three volume work that became celebrated in terms of a “new logic.” He was viewed by his admirers as a British version of Aristotle. Russell has been described as deducing mathematics from logic. “One of the effects has been not so much to subordinate mathematics to logic, which is what Frege and Russell wanted, but to subordinate logic to mathematics” (Ayer 1988:308).

Bertrand Russell became an influential Professor of Philosophy (Monk 1996). From 1910 to 1915 he was a lecturer at Cambridge University, during which period he was tutor to Wittgenstein, whom he regarded as a genius. Departing from mathematical logic, Russell composed some books on philosophy, including The Problems of Philosophy (1912). His Oxford follower Alfred Ayer referred to this work as “the best introduction to philosophy that there is” (Ayer 1988:309). Russell here describes “various traditional philosophical problems from an empiricist standpoint” (ibid). He was continuing the British empiricist tradition associated with Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. Russell is celebrated as having inspired the analytic philosophy favoured by universities, sharing this honour with G. E. Moore (Ayer 1971).

Later, Russell veered away from philosophy, engaging in political and educational activities having a flavour of radical socialism. He gained fervent admirers and strong critics. “The permissive society was implemented by Bertrand Russell, whose advocacy of free love is memorable for the misery created in his family” (Shepherd 2004:251). He married four times and became notorious as a womaniser. His book Marriage and Morals (1929) gained brickbats. In contrast, he later acquired the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950.

Russell was eventually hero-worshipped by the younger generation of the 1960s, who uncritically assimilated his political and social views, including the unwise disposition for free love that created so many problems. Russell was a symbol of pacifism and the campaign for nuclear disarmament, while also being noted for more questionable domestic conduct.

He wrote some further works on philosophy, including his famous History of Western Philosophy (1946). This book has received very differing assessments. The publisher Routledge refers to “the best-selling philosophy book of the twentieth century and one of the most important philosophical works of all time” (Routledge edition, 2000). A conflicting commentary came from Professor Bryan Magee, who says that Russell’s History is “overrated.” One judgment here reads: “The treatment throughout is superficial, not to say flip” (Magee 1998:220).

Furthermore, “for all his [Russell’s] genius he radically fails to understand Kant, and consequently the whole tradition of philosophy that has grown out of Kant’s work; his entire chapter on Schopenhauer is consistent with his never having read that philosopher’s main work” (Magee 1998:221).

These are weighty criticisms indeed. One is obliged to look closely at Magee’s personal description of Russell, whom he met towards the end of the latter’s long life, in 1960 to be precise.

Magee found that Russell was an elegantly courteous host, mentally alert at the age of 87, a fluent and humorous talker, and possessing a social record of impressive contacts the world over. For instance, Russell described how he had taught philosophy to the poet T. S. Eliot at Harvard. “He did not tell me what I subsequently discovered, that he [Russell] had had an affair with Eliot’s wife while the Eliots were living under his roof” (Magee 1998:264).

The subject gains due praise from Magee for his career achievements. However, significant contradictions for contemporary philosophy are emphasised. Although Russell is regarded as the founder of modern analytic philosophy, “he never regarded analysis as an end in itself” (ibid:216). Bertrand Russell started language philosophy, without viewing this as the objective, unlike his successors. More pointedly, “to the end of his days, he believed that the purpose of philosophy was what it had always been thought to be, namely the understanding of the true nature of reality, including ourselves” (ibid:217). In that respect, Russell was a polymath, not a specialist, and certainly not a linguist.

Even more pointedly, Bertrand Russell was one of the few who “understood clearly – what many people to this day fail to understand – that science of itself does not, and never can, establish a particular view of the ultimate nature of reality.” What science actually does is to “reduce everything it can deal with to a certain ground-floor level of explanation” (Magee 1998:218).

The Magee version of this perspective is memorable:

To many working scientists, science seems very obviously to suggest an ultimate explanation, namely a materialist one; but a materialist view of total reality is a metaphysics, not a scientific theory; there is no possibility whatsoever of scientifically proving, or disproving, it. (Magee 1998:218)

Magee finds the last philosophical book of Russell to be significant for reasons not always proclaimed. My Philosophical Development (1959) is described as a “substantial work aimed at the serious student of philosophy” (Magee 1998:220). The deduction is made that Russell was here acknowledging how his empiricist quest had failed. In the last paragraph, Russell states: “Empiricism as a theory of knowledge has proved inadequate” (ibid:222). Magee concludes that Russell finally arrived at a view which Kant had made a starting point in his own critical philosophy generations before. Moreover, Magee urges that Russell failed in pursuing logic and the philosophy of science, neither of these avenues having afforded a due explanation of known reality (ibid:219).

Ultimately, Magee views Russell as being impractical. His “genius was for solving theoretical problems” (Magee 1998:268). “He treated practical problems as if they were theoretical problems; in fact I do not think he could tell the difference” (ibid). This made Russell a “blunderer” in private and public life. “He had so little practical intelligence” (ibid).

The mathematical genius was thus at a disadvantage with real life problems of philosophy, which is not merely an academic or theoretical pursuit. Russell knew the limitations of language analysis; he apparently grasped, in the end, that his empiricist profile was a limitation. His flawed psyche (meaning his instinctual excesses) has been lamented by some commentators.

The most well known critique finds little of lasting value in Russell’s output from the 1920s onward (Monk 2000). The analytical philosopher became a journalist and popular writer on science and politics. He needed money to pay for his expanding family, a scenario of chaotic and tragic events. His difficult relationship with his second wife Dora was not assisted by the tendencies of both to frequent affairs. Their daughter Katharine Tait was the victim of a protracted feud between her parents. She eventually became a Christian, defying the atheist manifesto of her father (Tait 1975).

Russell abandoned his son John, who suffered a nervous breakdown. The pater was determined to get his son certified as insane and confined in an institution. The parental plan was for John to become a model of independence in purportedly progressive education. In fact, John became a schizophrenic. John’s daughter was also unstable, committing suicide at the age of 26, burning herself to death with paraffin. Biographer Ray Monk complains that Bertrand Russell, though a celebrated political activist, created disaster in his own home. The eminent rationalist was emotionally callow (Monk 2000). He was involved in two acrimonious divorces that produced severe problems for his children and grandchildren. Russell became estranged from his ex-wives, his children, and his grandchildren. His own admission is on record: “What a failure I have made of my life, as a husband and as a father” (Monk 2000:311).

Bibliography

Ayer, Alfred J., Russell and Moore: The Analytical Heritage (Harvard University Press, 1971).

——–“Frege, Russell and Modern Logic” in Bryan Magee, The Great Philosophers (Oxford University Press, 1988).

Irvine, Andrew David, ed., Bertrand Russell: Critical Assessments (4 vols, London: Routledge, 1999).

Magee, Bryan, Confessions of a Philosopher (London: Phoenix, 1998).

Monk, Ray, Bertrand Russell: The Spirit of Solitude (London: Jonathan Cape, 1996).

——–Bertrand Russell: The Ghost of Madness (London: Jonathan cape, 2000).

Russell, Bertrand, Principles of Mathematics (Cambridge University Press, 1903).

——–Problems of Philosophy (London: Williams and Norgate, 1912).

——–Marriage and Morals (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1929).

——–A History of Western Philosophy (1946; new edn, London: Routledge, 2000).

——–The Philosophy of Logical Atomism (University of Minnesota, 1949).

——–My Philosophical Development (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1959).

——–The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell (3 vols, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1967-69).

Shepherd, Kevin R. D., Some Philosophical Critiques and Appraisals (Dorchester: Citizen Initiative, 2004).

Tait, Katharine, My Father, Bertrand Russell (London: Gollancz, 1975).

Whitehead, Alfred North, and Bertrand Russell, Principia Mathematica (3 vols, Cambridge University Press, 1910-1913).

Kevin R. D. Shepherd

December 4th 2009, modified 2021